The lingering effects of El Niño are still being felt in the U.S. The deluge of rains that fell across the mid-south, southeast and eastern U.S. are a reminder of that. However, one agricultural meteorologist says as El Niño fades, La Niña is already knocking at the door, and it could bring dryness to the southern U.S. The biggest question is now timing.

Just last fall, 40% of the lower 48 states were experiencing some form of drought. Today, that number is cut in half thanks to the impacts of El Niño.

“I feel like the transition to La Niña is already underway,” says Brad Rippey, USDA Meteorologist. “The thing about that is that the impacts often are not felt for many months.”

Rippey says just like the impacts of El Niño are still being felt four months after its peak, the claws of La Niña may not come until fall.

“Even if we make that transition into La Niña by, say, summertime, we’re likely not to feel the impacts of La Niña until we get into the autumn of 2024,” Rippey says. “So that’s good news for the growing season.”

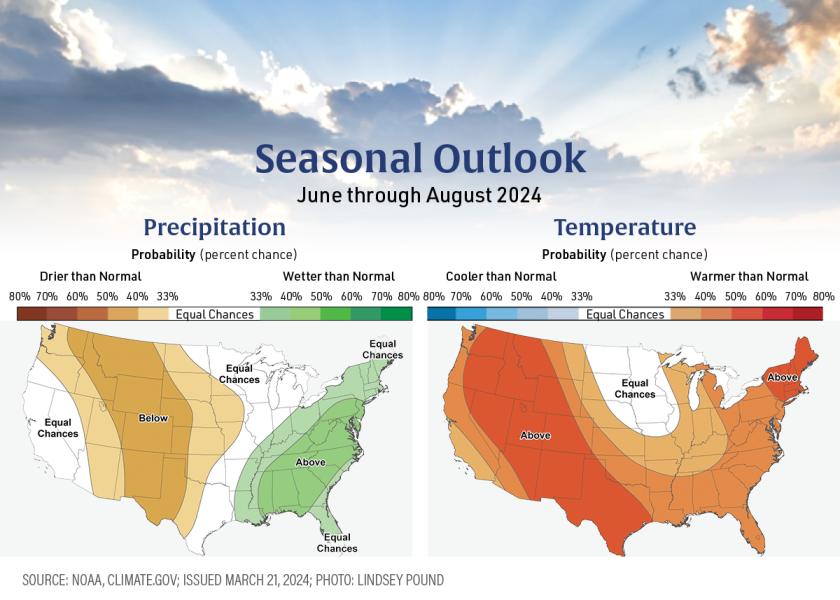

According to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association (NOAA), there’s now a 60% chance that La Niña will develop between June and August. NOAA still thinks by November 2024 to January 2025, there’s an 85% chance a La Niña will be in effect. The tropical Pacific Ocean continues to trend toward a La Niña phase, coming out of one of the strongest El Niño events on record since 1950.

Spring Forecast Barrier Makes it Hard to Predict

What could the transition mean for growing conditions in the U.S.? Eric Snodgrass, science fellow and principal atmospheric scientist for Nutrien Ag Solutions, says the transition to La Niña is so hard to predict because of something atmospheric scientists call the spring forecast barrier.

“What we found is that our ability to predict well how El Niño is going to transition before you get through the month of May is pretty bad,” Snodgrass says. “Once we get into May and start to pay attention to those ocean temperature changes. We’ll be much better at predicting it, and a lot rides on it.”

Snodgrass looked back at history, and he says every time El Niño peaked at Christmas then faded until it was eventually replaced by La Niña in summer, it created a drought scenario in the Cotton Belt.

“Some of those years it was over Texas, some of those years it was in the Delta and some of those years it was in the Southeast,” Snodgrass says. “But if you keep drought down South, we tend to get ridge riding storms over the top of it in the Corn Belt, so the Cotton Belt gets the stress and the Corn Belt tends to do better.”

“I do think one thing about this summer, and that is I’m expecting warmer than average temperatures,” Snodgrass says. “Most of that coming in warmer overnight lows though, based on what I know now. And a lot of that is predicated on the collapse of El Niño to neutral conditions and eventually into La Niña.”

Whether it turns into a hot and dry summer or a much wetter forecast than some are anticipating, Snodgrass says he was burned by weather prediction models last growing season, so he’s skeptical to rely on those again. However, he does think La Niña could open the door for a very active hurricane season this year.

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K