Yes, food prices are up. But no, average U.S. milk prices aren’t skyrocketing — they’ve basically stayed the same since January.

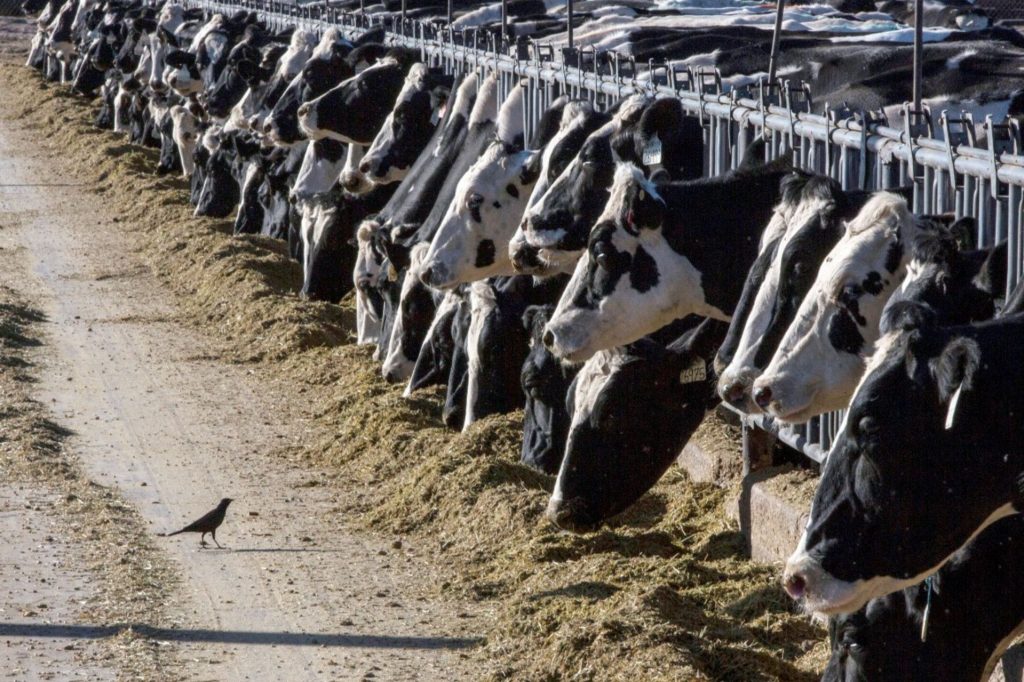

That’s because the U.S. overall has an oversupply of milk, and it’s gotten worse over the past few decades as smaller farms have shuttered and larger farms have bought up their livestock and increasingly dominated the industry.

It’s been a problem that policymakers have been struggling to confront for years. And it’s not clear that Washington, D.C., will address this issue because other food prices have been rising much more as a result of the pandemic-induced supply chain breakdowns. The Biden administration has pledged to address antitrust issues in industries ranging from technology to meatpacking. But so far, the dairy sector hasn’t been the focus yet in part because consumers aren’t seeing significantly higher prices as a result of consolidation.

A CNN report this week triggered a brief social media spectacle after it featured a family saying retail milk prices skyrocketed (up 79 cents a gallon over just a few weeks for that couple in the Dallas area who were interviewed and said their family consumes 12 gallons a week). In fact, the average price of milk nationally has largely stayed steady throughout the year, according to the Agriculture Department.

Overall, the U.S. has been making more milk than it can use. “The availability and supply of milk is not a concern, it’s a concern about moving that milk to where it’s needed,” said Matt Herrick of the International Dairy Foods Association, one of the largest dairy lobby groups in the U.S.

Certainly, some cities have experienced isolated price swings in milk prices — though not as large as the family on CNN noted — as a result of local supply issues and other factors. Since the beginning of 2021, a gallon of whole milk has increased 43 cents in Dallas, 32 cents in Kansas City, Mo., and 22 cents in Miami, according to USDA data.

But the average retail price of whole milk in the United States since the start of the year has increased just 3 cents, to $3.69 a gallon. That means milk prices are up less than 1 percent, in contrast to around a 5 percent increase in the benchmark consumer price index over the same period.

For now, the White House is paying attention to the complaints about grocery prices, but it’s more intensely focused on the steep jump in the price of meat and poultry, which has made Democrats vulnerable to Republicans’ political attacks on inflation.

“Milk isn’t the issue,” a senior White House official said. “You haven’t seen a huge spike in prices, but for some meat prices it’s gone up substantially. That’s because it’s more vulnerable to these kinds of spikes.”

The White House in September slammed giant meatpackers for “pandemic profiteering,” while Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack introduced several regulations to step up USDA’s enforcement of antitrust laws governing the meat industry.

Small dairy farmers had hoped the Biden administration would tackle consolidation in their industry early on, especially after the Obama administration pledged to take on the issue but then backed down after the dairy lobby pushed back. Vilsack, who had been Agriculture secretary throughout the Obama administration, had taken on the role as head of a large dairy lobby before returning as head of USDA.

“There’s been a lot of good announcements from the Biden administration, but the biggest issue is that there hasn’t been any real action yet,” said Darin Von Ruden, the president of the Wisconsin Farmers Union who runs a small dairy farm in southwest Wisconsin.

The White House was planning for President Joe Biden and Vilsack to visit a dairy farm in Von Ruden’s area of Wisconsin earlier this year to address agricultural issues and his larger agenda. But when a group of Republicans got on board the bipartisan infrastructure plan just before Biden’s planned trip, White House officials moved the location to a transportation hub in a nearby city. Biden instead focused on how the bill would put electric buses on roads and he mentioned its rural broadband investments.

This summer, Vilsack called small, family-run dairy farms the “life-blood of many rural communities.” But he, like many in the White House, have been focused on tackling antitrust concerns in the meatpacking industry.

“We want to maintain and expand our family operations, but when 90 percent of family operations don’t make the majority of their income from the farm operation, something’s got to change,” Vilsack said in July while announcing $500 million from the USDA to expand meatpacking capacity in the U.S., especially for smaller companies.

The federal government has tried various programs over the years in an effort to address the glut of milk in the U.S., with mixed success.

The current main vehicle to aid dairy farmers has been the Department of Agriculture’s Margin Protection Program, which acts as a kind of insurance to help farmers stay afloat, especially small farms. They pay into the program and receive payouts if their costs of operating rise too high compared to the prices at which they’re able to sell milk.

Tony Hammell, who runs a 300-cow dairy farm in rural Minnesota, is one such farmer who has participated in the USDA program. But he’s acutely aware of the cost benefits that a neighboring farm a few miles away has with several thousand cows.

“They can start with a bare field and build a 10,000-cow dairy. I don’t know how you can compete with that,” Hammell, who is 66, said. “It’s pretty much impossible I would say, just hanging in there is just about all you can do.”

Hammell said that the USDA’s program has been helpful to make ends meet for his farm, which he runs with his 32-year-old son, Drew. But Hammell argues the federal government should implement a quota program, which would limit the amount of milk farms can produce.

In the U.S., larger farms, and much of the dairy lobby, have pushed back against those protections for small farmers. They argue the free market should decide who stays in business and that the federal government shouldn’t dictate how much they’re able to produce. (Canada’s government operates a “managed” program that controls the supply of milk through a quota system and provides subsidies to protect its smaller farmers.)

In Europe and elsewhere, demand for U.S. dairy products is up and U.S. producers now rely on those strong export markets.

But the harsh reality for the U.S. dairy industry is that Americans are drinking less milk per capita than ever, while consumers are also turning to more soy, almond and other milk alternatives.

“There isn’t a market for it,” Hammell said of the push for dairies to expand and produce more and more milk. “It’s just that they can do it so much cheaper than everybody else, that’s why they can stay around better than us.”