“All of my cows were affected,” Siswantoro said through an interpreter, when asked about the impact of FMD on his larger than average 29-head cow herd.

“Hopefully, the wave has now passed and we can begin producing milk again.”

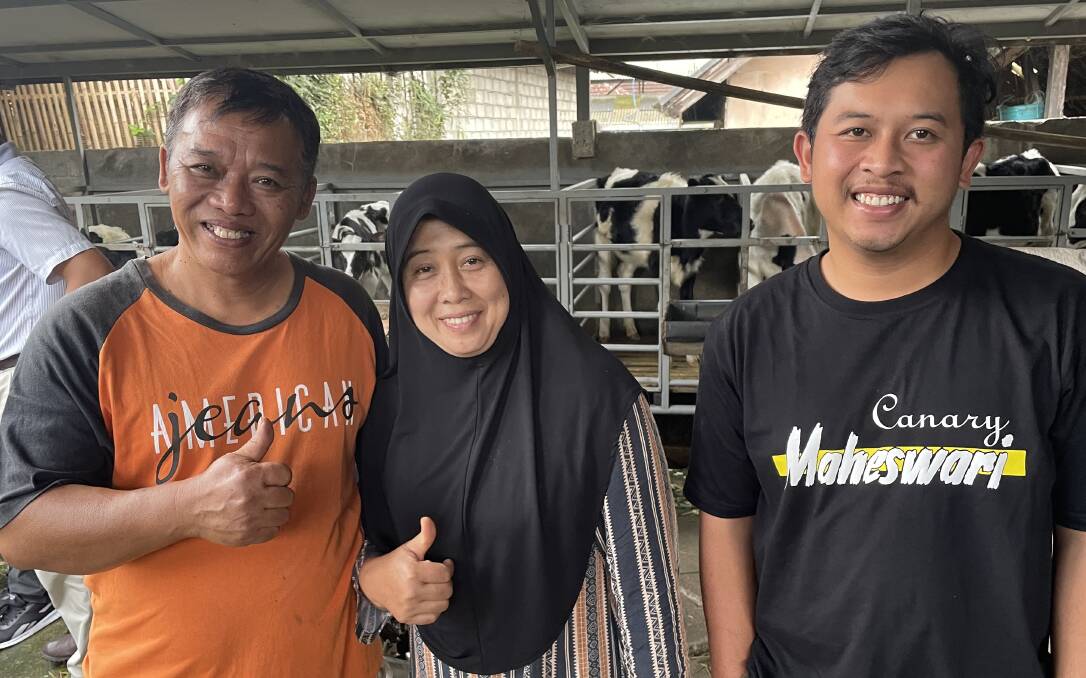

On another nearby farm Dito Fachrizal and his parents Sujani and Siyanah also saw the production from their 18 cows fall equally as dramatically.

“Everyone was caught out,” Sujani said, also speaking through an interpreter.

“Farmers knew there was a problem and started selling infected cattle for very low prices, but didn’t say they were sick.

“Cattle that were 30 million rupiah (A$2900) were suddenly selling for 5 million rupiah (A$500).

“Who could resist. These cattle were so cheap.”

Value of milk

The high value of cattle reflects the incredible value placed on milk in Indonesia as part of the developing nation’s determination to be self-sufficient in food.

In addition to the demand created by the nation’s population of 273 million people, milk is seen as an essential way of reducing the estimated seven million children under five years old suffering from stunting.

Yields are low compared to Australia. Cows in the smallholder farmer ‘cut and carry’ feeding system are producing 10 to an optimistic 12 litres of milk a day.

What is certain is that a lack of biosecurity compounded by largely unrestricted livestock movements, a grossly inadequate vaccination program, and only basic on-farm hygiene practices are combining to make the control of the disease virtually impossible.

Indonesia’s housed and tethered dairy herd appears to have suffered close to a 100 per cent infection rate.

One of the other few positives is that mortality rates appear to have been relatively low.

Initially from India

Indonesia’s FMD outbreak is most likely linked to infected meat brought from India, based on the knowledge that the ‘O’ type variant currently running rampant across the archipelago was initially detected in India.

While Indonesia has a policy of preventing product from being imported from FMD countries, it also has an emergency trigger price on meat set at about US$8/kg, which enables the rule to be bypassed.

The impact on the 16 million head beef herd is less clear, partly because farmers are reluctant to report incidences of disease outbreaks.

The Indonesian government also appears reluctant to draw negative attention to Indonesia in the run-up to the G20 Bali summit in November.

Feedlot outbreaks

It is understood that at least 26 of Indonesia’s 30 main beef feedlots are infected with FMD.

However, the risk is not only to Indonesia’s 16 million cattle. The country has an estimated 65 million ruminants along with a significant nine million head pig population.

The painful FMD lesions, which can stop cattle from standing and preventing them from being able to eat or drink, are primarily being treated on the feet with copper sulphate. Acidic citrus juice is commonly used to treat the lesions in the mouth, with both treatments adding to the pain levels already being suffered.

Cattle are also liberally dosed with “jamu”, a traditional home brewed tonic comprising of a range of natural remedies including tumeric, ginger, brown sugar and boiled madeira vine leaf.

Fragile virus

Professor Emeritus Peter Windsor from the University of Sydney said while not particularly robust, the FMD virus was highly infectious.

Speaking at the invitation of the UMM University in Malang, Prof Windsor said vaccinations would not eradicate the disease on their own.

“Vaccinations would be most effective ahead of the infection and to provide protection for uninfected, higher value animals,” he said.

“Vaccinating animals that have already been infected with FMD will achieve little, as those animals will gernerally have pretty good lifetime immunity, while the vaccine will only last about six months.”

Prof Windsor also encouraged the use of the Australian-developed pain relief product Tri-Solfen for animals showing clinical signs of FMD, saying it not only killed the virus, it provided sufficient lasting pain relief for affected animals to stand, drink, eat and recover.

FMD is currently officially declared in 23 of the Indonesia’s 37 provinces spread across the 5100km wide archipelago.