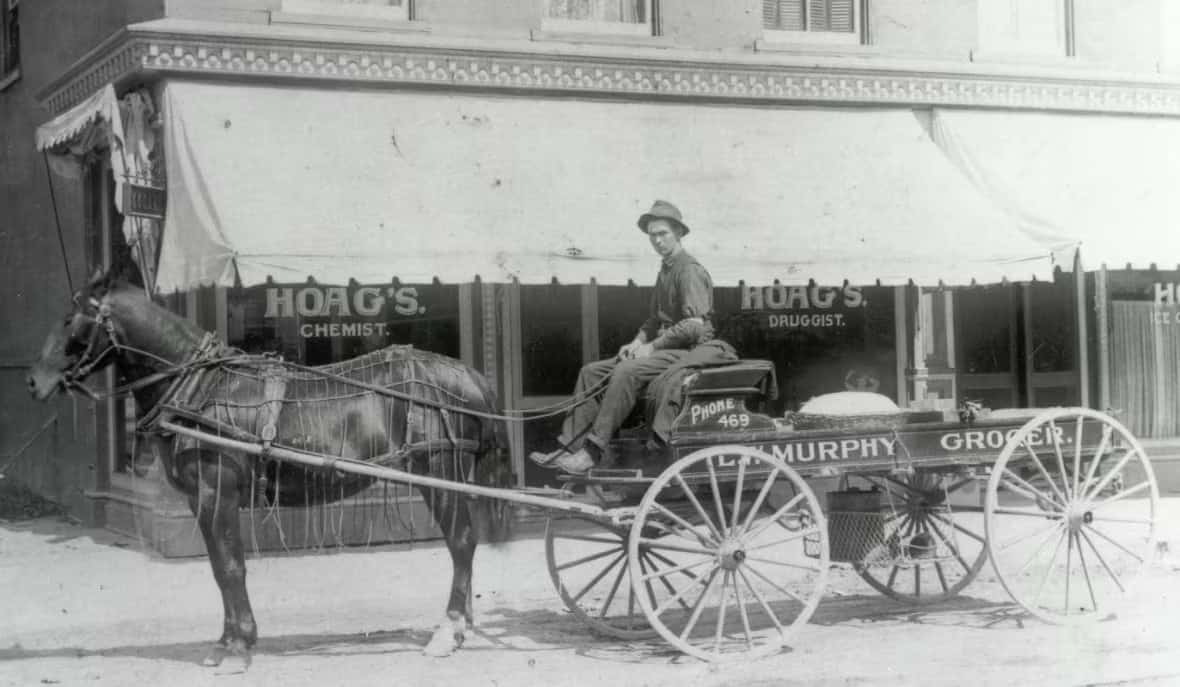

Imagine life in Kingston, Ont., 100 years ago: the clopping of hooves, the scent of manure in the air — and the persistent sound of mooing.

Local historian and Queen’s University PhD candidate Claudia Hirtenfelder says cows may not be the most recognizable feature of the 19th-century urban landscape, but they did play an important role in daily life.

She doesn’t want us to forget that.

“We tend to think of human histories, but we don’t think of animal histories,” she told CBC Radio’s Fresh Air. “It took looking at massive amounts of information to find the animals, and then it took taking those traces of them in the archives seriously.”

Hirtenfelder, an urban geographer, scoured records for mentions of the animals, finding references in inspection reports and news articles about everything from the threat of tuberculosis to the “horrible stench.”

Using materials from 1838 — when Kingston was incorporated as a town — up to 1938, she was able to see how the urban environment changed.

A forgotten symbol of that shift: the bovine population.

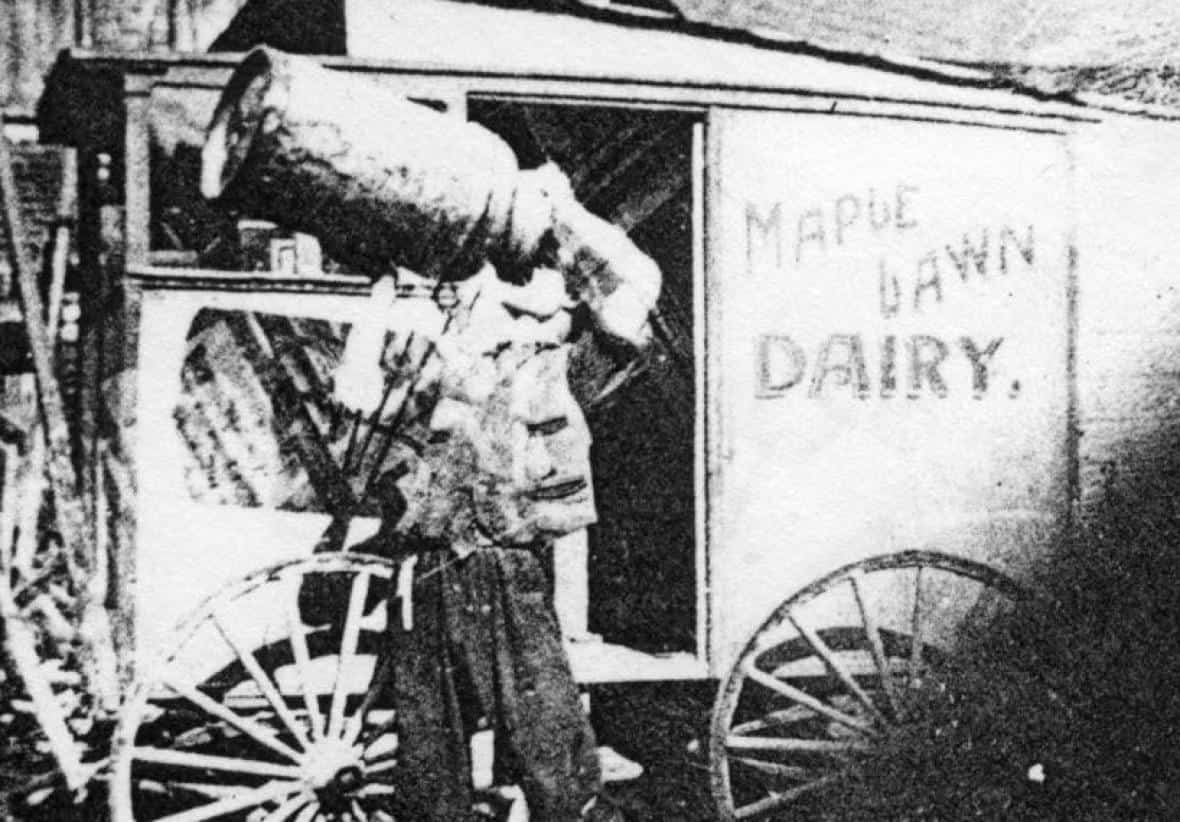

Milk doesn’t travel well

The city was home to more pastures than many realized, said Hirtenfelder. Milk didn’t travel well, “so a lot of folks kept cows so they could have milk close by.”

“This included wealthy people, but also working class and establishments like hospitals and breweries.”

Morton’s Brewery reportedly had close to 1,000 cows, which it fattened up for the slaughter.

She connected people with that history at a recent heritage talk, with its sights, sounds and smells — which she describes as “quite different.”

“You would have been walking down the street and manure would have coated the street from horses and cows, and it would have mixed together creating a very distinct, kind of farm-like smell in the city,” said Hirtenfelder.

One letter to the editor from the time described the odour as an assault on the nostrils that makes the air wafting from rubber factories seem like rose perfume.

Why cows were told to move on

Pigs were originally seen as the scourge of the fledgling town, according to Hirtenfelder. As the century went on, cows became a more common topic of conversation, and complaint, at committees.

Cows that provided milk to patients at a local mental hospital were infected with tuberculosis, creating a health panic, and there were disagreements over damages caused by the animals.

Hirtenfelder said cows were only discussed as property, but she tries to imagine them as living beings.

“I talk about how she was pasturing just outside the courthouse grounds,” she said of one of the evicted animals, “And how she enjoyed standing in a slither of sunlight.”

She encourages other urban dwellers to think of their own bovine connections.

“They might not be in our cities as lively beings, but they are leather and they are milk and they are meat,” she said.

“We have this imagined disconnect, but we are still very much in a relationship with cows today.”