Speaking at the Dairy Industry Newsletter conference in central London, Patrick Müller said the liquid milk industry is at tipping point due to a lack of profitability.

With consumption of milk in decline, he said supermarkets, processors and farmers need to work together to create more value-added products and export more if they are all to remain profitable.

“We have to get rid of all the cost that is not seen as value added for customers,” said Dr Müller, explaining the company is also exploring more long-term strategic partnerships and looking at how it can make further savings to the cost of milk transportation.

The company currently has the exclusive contract to supply liquid milk to a number of supermarkets, including Sainsbury’s and Tesco, alongside its highly popular own-label yoghurt and dessert range.

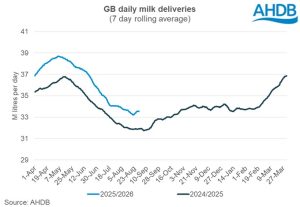

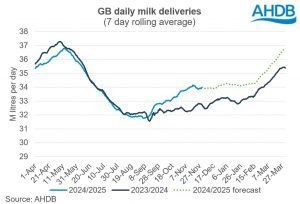

Farmgate milk production hit a 30-year high this spring, as a mild winter and early spring saw production from grass race ahead. Müller responded by cutting its non-aligned price for March to 26.25p/litre, and has since held it at that level, below some of its rivals.

Dr Muller suggested the company may look to expand its offering of farmer contracts in future to offer both itself and farmers more certainty on pricing.

Müller launched a fixed-price contract 12 months ago for non-aligned farmers to commit up to half their milk production for three years at 28p/litre, and a futures price-linked contract in 2017.

Sale of milk in decline

The volume of milk sold in the UK fell by 70m litres last year (a 1.7% decline), as tea and breakfast cereal consumption declined and more consumers chose alternative plant-based products to add to their coffee.

Globally, 15% of the dairy market is now made up of non-dairy alternatives, with a 50% increase in sales of non-dairy cheese, cream, butter, yoghurt and ice cream in the US in 2018.

“If we don’t listen to what consumers want, we have a problem,” said Dr Müller. “I am an absolute, firm believer that every successful business has to be demand-led.”

Cost-cutting programme

The company announced in February it was to make £100m in savings as part of a cost-cutting programme called Project Darwin, and confirmed at the end of April that this included a consultation on the viability of its six processing sites.

A company spokesman said the consultation would end by mid-June and the firm would then take time to consider the findings before arriving at any decision.

However, the site earmarked as being most likely to close is Foston, in south Derbyshire, according to the factory workers union Usdaw.

Where could extra dairy demand come from?

Despite gloom around the decline in liquid milk consumption, there are still major opportunities for British dairy companies to place more product domestically and abroad, according to Nicholas Saphir, chairman of organic dairy co-operative Omsco.

The UK imports milk products worth £1.2bn/year, in contrast to other north European countries that are chiefly exporters, which processors could go further to replace.

However, it will not be until exports increase that domestic prices will show significant improvement, as it will force supermarkets locked in a low price strategy to pay more for milk or lose it to a more lucrative market, Mr Saphir said.

With the global organic dairy market growing at 10% a year, to a value of $90bn last year, this is one sector that can be targeted, he said.

The value of organic sales are also growing in the UK, with cheese and butter volumes up, while yoghurt and milk is static.

Dairy is well positioned to adapt from a liquid-led sector to one that is focused on value-added propositions, agreed Fonterra’s European sales director, Francis Reid.

The company is developing partnerships with a number of European dairy processors to create Fonterra products using locally produced milk.

He said processors had three key growth areas around which they can market a positive story of dairy; nutritional drinks for the medical sector and to support healthy aging, products for sports and active lifestyles, and infant formula.

A number of these products uses whey – a byproduct of which Europe produces 9m tonnes/year, although the majority is still fed to pigs.

This is in contrast to the New Zealand dairy sector, which is already putting all the whey it produces into high-value products.