Dairy farmer Jennifer Beretta talks on July 15, 2021, about the impact of the drought

on her family's dairy farm in Santa Rosa. She's had to cull some of her herd

as its become more expensive to feed the cows because of water restrictions. BY RENÉE C. BYER

“I raised them from when they were babies,” said Beretta, 33. “I watched them grow up to be milk cows. You get attached to them. They have personalities.”

But business is business, and right now business is bad. California’s devastating drought has dried up most of the Beretta Family Dairy’s pastures, driven up the cost of feed and made milking cows unprofitable. The Beretta family has sold off more than 40 of its cows this year, and could sell more before too long.

“If you can’t afford to feed them, you don’t want to go into debt,” Beretta said. “It’s frightening. … You just try to prepare for the worst.”

All over California agriculture, water sources are being reduced to a trickle. Fields have been idled and even some fruit and nut orchards are being dismantled because of shortages. Based on what happened during the last drought, the financial losses to agriculture will be enormous.

In short, California’s $50 billion-a-year farm economy is turning nightmarish. And nobody’s losing more sleep than the state’s dairy farmers and beef-cattle producers, who are scrambling for feed to keep their animals alive.

“It’s pretty much statewide,” said Tony Toso, a Mariposa County beef rancher and president of the California Cattlemen’s Association. “My goodness, there’s pastures out there that just look like moonscape.”

Raising cows for milk or meat is a $10 billion-a-year business in California — bigger than wine grapes, bigger than almonds, bigger than anything else in the agricultural sector. But the drought has quickly turned the economics of dairy and beef upside down. Faced with steep increases in the cost of feed — assuming they can find it — beef and dairy farmers are watching their profits disappear.

The result is, many are selling off animals at a pace rarely seen.

“We are absolutely seeing a liquidation of cows, particularly from the West,” said Don Close, who analyzes the beef market for agricultural lender Rabobank.

So far the drought isn’t raising consumer prices, but that’s likely to change. In the meantime, ranchers and dairy producers are getting squeezed financially by higher costs — and are left with dwindling options.

“You’re going to have to cull your cattle,” said Tracy Schohr, a rancher and livestock advisor for UC Cooperative Extension in Quincy. “You’re going to have to make decisions about which cattle to sell.” Her ranch sold 15 animals earlier this year.

A few ranchers are selling them all, including Greg Kuck, a beef producer in Montague, Siskiyou County, who recently agreed to unload his entire herd — numbering hundreds of animals — and retire.

“The water here just got so depleted,” said Kuck, 67. “It’s been pretty hard on everybody, watching their ranches dry up.”

WILL CONSUMERS PAY MORE BECAUSE OF DROUGHT?

Consumers have been paying more for beef in the past few months, although the drought isn’t the reason why. Close said prices are being driven by bottlenecks in the packinghouse industry.

After being forced to reduce slaughter operations last year because of COVID-19 outbreaks in their workforce, big meatpackers are now struggling to ramp up because of the nationwide labor shortages that have plagued the economy, Close said. Average retail beef prices nationwide have risen nearly 13% since January, according to his analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

Where does the drought come in? Ironically, it could bring prices down in the short run. As ranchers and dairy producers cull their herds, more and more animals will get turned into hamburger meat, glutting the market.

But over the long haul, the situation will reverse itself because of the shrinkage in herd sizes. There will be fewer products in the coming months and years.

“Culling cows now lowers the price for hamburger now and it means steaks will be more expensive two years from now because there are fewer calves,” said Daniel Sumner, an agricultural economist at UC Davis.

Consumer prices for dairy products have held reasonably steady. The nationwide average for a gallon of milk was at $2.75 in mid-July, the same as a year ago, according to the USDA. A 16-ounce tub of sour cream has actually gotten cheaper — $1.77 compared to $1.85 last year.

As it happens, there are plenty of dairy products — and dairy cows — even if feed prices are hurting farmers’ pocketbooks.

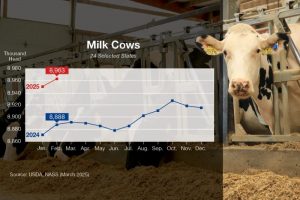

“This is one of the largest herd sizes since 1994,” said Ken Gott, president of Clover Sonoma, the big organic dairy processor based in Petaluma. “There’s not a shortage of milk.”

However, Gott said conditions should change before too long as farmers’ woes pile up and herds shrink.

“I would anticipate there would eventually be upward pricing pressures,” he said.

The impact could be fairly long-lasting. Anja Radabaugh of Western United Dairies, a trade organization based in Turlock, said the culling of herds is a process that can’t be reversed overnight.

“Once the herds are reduced you’re talking a couple of years before they get back up again,” she said.

Radabaugh added that some of the dairy cows — the ones not being turned into hamburgers — are being sold to out-of-state producers with better feed supplies, she said. That translates into permanent reductions in dairy production in California — a humbling development for a state that overtook Wisconsin in 1993 for the title of the leading American dairy state.

“It’s a sad day for California when people are buying Texas dairy products,” Radabaugh said. “As dairy sizes shrink, that’s where the herds are going — Texas, Utah. We call it leakage.”

CALIFORNIA FARMERS GET PINCHED BY COSTS

Dairy farmers in California get $7 billion a year for their cheese, yogurt and other products (Only about 11% of their products are sold to consumers as fluid milk). California’s beef ranchers do about $3 billion a year in sales, according to the Department of Food and Agriculture.

As big as they are, however, California livestock producers can’t drive prices, according to UC Davis’ Sumner.

In some commodities, such as almonds and raspberries, California farmers dominate U.S. production. But California produces just 18% of the nation’s dairy goods and less than 5% of its beef.

That means that even though their costs are soaring, that doesn’t translate into immediate increases in the prices they’re paid for their commodities, Sumner said.

“That’s bad news for the cowboys,” he said. “They’re really not going to make it up on price.”

Jim Rickert, who raises 2,800 beef cattle near Macdoel in Siskiyou County, has watched conditions steadily worsen this year — rising production costs without any relief on the price he gets for his animals. The drought wiped out much of the grass on his pastures; the Tennant Fire burned up a large field.

“That was 250 acres, just gone,” said Rickert, who co-owns Prather Ranch with his wife Mary. “At one point I thought we were going to lose buildings.”

The future doesn’t look much better — Rickert is afraid he’s going to have to seriously cull his herd if next winter is as dry as last winter.

“We’ll have to make some serious decisions about how many cattle we’re going to keep and how many we’re going to have to sell,” he said. “I’m going to run out of forage and I’m going to run out of bank account.”

In the Esparto area of Yolo County, cattle rancher Scott Stone is making the same grim calculations.

“I don’t have any feed,” said Stone, a partner in Yolo Land & Cattle Co. “I’m anticipating a 30 to 40% reduction in my cow herd.

“I’ll be loading them on the truck and they won’t be coming home.”

A CALIFORNIA DAIRY FARM COPES WITH DROUGHT

The Berettas have been raising dairy cows in Northern California since the late 1940s, when Jennifer’s great-grandfather Joe set up shop. The family operates two separate dairy farms, one in Marin and one in Sonoma. Jennifer has worked in the business in Sonoma since she was old enough to “push the tractor pedals,” she said.

Worlds away from Sonoma County’s elegant wine country, the Beretta Family Dairy is a collection of nondescript barns and other buildings on a rural road southwest of Santa Rosa, surrounded by around 500 acres of pasture. Beretta sells exclusively to Clover Sonoma; the farm’s annual sales are something north of $1 million.

The dairy sits maybe 10 miles from the Russian River, one of the most troubled waterways in California. The watershed was the first region of California to be officially declared in drought by Gov. Gavin Newsom, back in April.

Long before Newsom stepped in, the Berettas knew they were in trouble. Water supplies were cut 30% last year and another 30% this year. A flood-control channel that carries water to the Russian River is “dry for the first time in my lifetime,” Beretta said, and most of the pastures have completely dried up. The one parcel that’s still being watered — it’s all of 30 acres — is almost as much brown as it is green.

Because their farm is certified organic, the loss of pastureland creates complications. Beretta said the farm had to receive a special variance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to reduce the number of days the cows spent grazing on grass, according to Jennifer Beretta.

Losing pasture is also extremely costly. Beretta said her farm is bringing in truckloads of hay at least three times a month from Oregon and Nevada. The price is $345 a ton, up from $285 a year ago.

Meanwhile, the price farmers get from the big creameries such as Clover Sonoma has held steady. Farmers sell their milk in 100-pound increments (a gallon of milk weighs 8.6 pounds), and the current price is around $30 to $33 for every hundred pounds.

Beretta said farmers need to be paid a higher price.

“As all these (production costs) start to rise, we’re hoping the creameries can give us a little bump,” Beretta said, “because right now we’re barely at break even.”