On July 22, 2017, the disease – which can have serious effects on cattle, including mastitis, abortion, pneumonia and arthritis — was confirmed in New Zealand, triggering the country’s largest and most expensive biosecurity response.

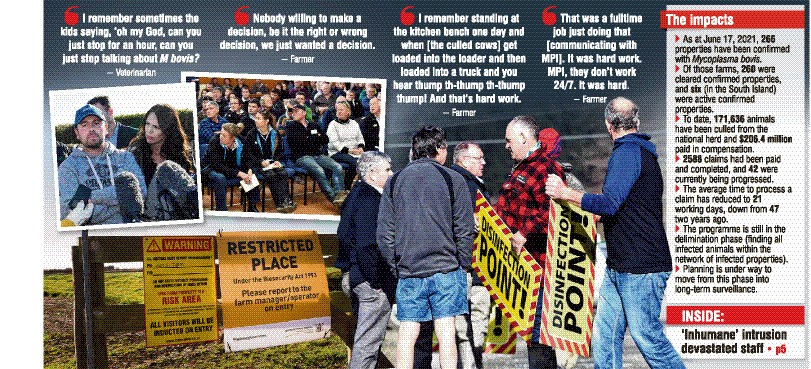

That response came at a cost – not only the whopping price tag of the eradication plan but also the very real human and animal toll the disease took.

The study, which looked at the psychosocial impact of M. bovis on rural communities in the South, revealed the enduring emotional cost of a “badly planned and poorly executed process”, which left farming families feeling isolated, bewildered and powerless.

A dominant theme of the research was the “intrusive, impractical and inhumane nature of the MPI (Ministry for Primary Industries) eradication programme in which local knowledge, expertise and pragmatism were ignored in favour of inefficient bureaucratic processes which made no sense to farmers”, a statement said.

Others in the rural community, including local veterinarians, felt their expertise was undervalued and their potential to positively contribute to the management of the outbreak was disregarded.

Extensive interviews were conducted with affected farmers in Otago and Southland.

The research was done by Dr Fiona Doolan-Noble, Dr Geoff Noller and Associate Prof Chrys Jaye, of the University of Otago’s department of general practice and rural health, and Southland veterinarian Mark Bryan.

Last night, the study team discussed its findings from the two-year project at a meeting in Winton.

One farmer interviewed said he quit the land because of the impact of the elimination programme and he could not recall the birth of a child because of the stress at the time.

The report noted another disease incursion was inevitable and solutions needed to be sought from within rural communities and then integrated into the relevant bureaucratic processes.

One of the Ministry for Primary Industries’ key principles, in terms of biosecurity, was fair restoration – “no better or worse”.

The researchers believed that should apply not only to the financial impact on farmers but also to the effect on both the mental health of all involved and the social wellbeing of rural communities.

Their findings highlighted the current approach was not effective in those areas.

That schism was likely to widen in future incursions if attempts were not made to better match the centrally directed, inevitably bureaucratic processes with the needs of key local players, especially farmers and veterinarians.

They proposed:

- The development of a regional interprofessional body to develop pragmatic approaches to future incursions.

Genuine local engagement to seek solutions from the ground up. - The formation of a nationwide “standing army” of rural-based experts who could be called on to help shape the response to the next incursion.

- In a statement, study lead Dr Doolan-Noble said it was “heart-wrenching” listening to farmers’ accounts and also those of veterinarians and frontline workers.

“During the two-hour journey back to the university from Southland (where the majority of interviews were conducted), we [she and Dr Noller] had to be there for one another, to just discuss the stories we each had heard.”

The disease was first detected on two properties in the Waimate district owned by large-scale dairy farming operation the Van Leeuwen Dairy Group.

For the first few months, the focus was on the VLDG but, months later, it was revealed Southland was believed to be where the disease first took hold.

The farming operation at the centre of the outbreak was Southern Centre Dairies, owned by Alfons and Gea Zeestraten. Mr Zeestraten has previously told media he and his wife were good people who had been portrayed as criminals.

He said he did not know how the disease got on to his farm, and he had done nothing illegal, including illegally importing any bull semen or drugs that could have carried M. bovis into the country.

The report said farmers were paid compensation for lost stock, but that was often perceived as inadequate and hard work to secure.

Farmers described the damage to their sense of identity and the forced separation from typical farming practices and seasonal rhythms as they transitioned into an incursion management process overseen by an ill-prepared government agency.

Once a notice of direction was issued for a property, farmers effectively lost control of the running of their farm while remaining responsible for the welfare of their remaining stock.

That situation was compounded by poor communication; lack of clarity about animal-testing regimes; delays in providing results; indecision regarding stock management; authoritarian and, at times, brutal decision-making concerning herd culls; and ignoring practical solutions to on-farm problems.

A beef-farming family was affected by slow MPI decision-making, resulting in their farm over-wintering too many cattle during a very wet season.

“The animal welfare of the animals was not good at all … because they were on very small pads in mud up to their haunches …

“We had two or three pass away on our pad because the conditions were so rough.”

Another farmer recounted how MPI officials insisted on following the mandated process of decontaminating a shed at a cost of $150,000, when he could have had it rebuilt for $70,000.

Another described how a cleaning team was paid to sit at a table dipping individual screws into disinfectant and scrubbing them clean with a wire brush, when the cost of new screws was negligible.

Study participants noted farming was a 24/7 business but MPI officials were unavailable at weekends or over holiday periods. However, they did not necessarily blame MPI staff.

“In MPI, there’s a lot of people really, really trying. And they’re just getting caught up by red tape,” one farmer said.

The researchers were guided by a stakeholder panel which included representation from farmers, veterinarians, local business, (human) health professionals, rural organisations, agribusiness and the MPI.

Oversight was provided by a governance group comprising a Maori representative, a public health expert, an ethicist, a retired veterinarian and a farming consultant.