That’s because in Maine, as long as a dairy producer has a valid Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry dairy license, a simple heat treatment process can be used to pasteurize milk. It’s a less expensive process than the federal pasteurization standards used in the other 49 states.

The ability to work with heat-treated milk, they say, allows small farms and creameries the freedom to explore different products and diversify without first having to make a substantial monetary investment.

It’s also something that agriculture officials say does not come at the expense of dairy quality or safety.

Pasteurization is the process of heating milk to at least 145 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes. The higher the temperature used in the process, the shorter the time it takes. Outside of Maine, it must be in compliance with the United States Department of Agriculture’s pasteurized milk ordinance — or PMO. That means the process must include technology and equipment that records and documents those temperatures and times.

Heat treating is basically the same thing without the technical recording equipment. Instead, that information is recorded in written logs and based on observation.

Maine is also one of 13 states that allows the sale of raw milk at the retail level. Raw milk is milk that has not been treated in any manner.

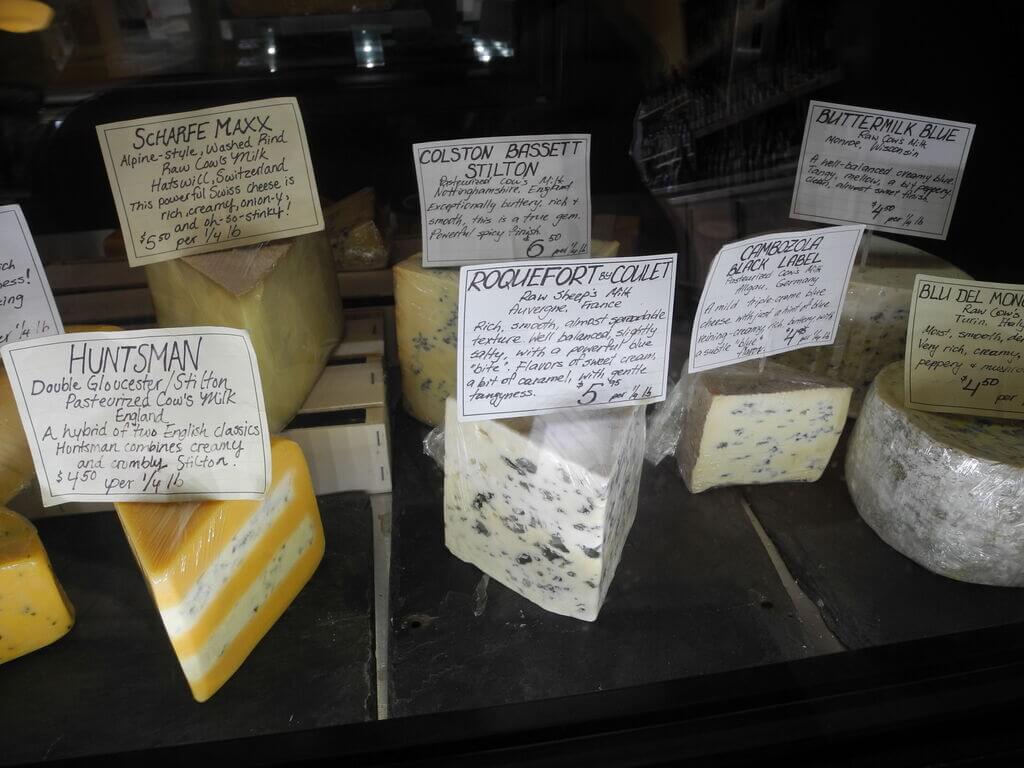

For value-added products, though, the low-tech method of pasteurization opens the door for producers to experiment more, according to Eric Rector, former president of the Maine Cheese Guild. In Maine, any cheese or yogurt aged less than 60 days that is destined for retail sales must be made with milk that has been pasteurized.

“Those federal pasteurization standards are not conducive to what we do in Maine,” Rector said. “There are some dairies and creameries that would go out of business if they had to change over to PMO standards.”

The cost of PMO compliant equipment is around $10,000. It’s a cost that would be difficult for many small creameries in Maine to afford, according to Heather Donahue of Balfour Farm and The Little Cheese Shop.

She said Maine allows cheese makers to use simple vats to heat treat raw milk. They keep careful written records throughout the process that are available at all times to state dairy inspectors.

“Instead of fancy equipment, [they] are the timers and temperature monitors,” Donahue said. “What [they] write down becomes the legal record and this is something that has allowed small creameries in Maine to flourish.”

It also gives creameries the ability to more easily diversify, said Rector.

In Rector’s case, it means he can use heat-treated milk to make yogurt while he waits for up to two months for his cheeses to properly age before he can sell them.

“This allows me to keep my business humming along and to keep the money rolling in that supports the long-term aging of cheese,” Rector said. “Heat treatment is a wonderful option for small dairies who need to maintain a cash flow.”

Heat-treated milk products can’t be sold outside of Maine, creating a unique niche that cheese lovers can only find in the state.

Rector is quick to point out the heat treating that is permitted in Maine is very different from the process used in many European countries known as “thermized heating.” This process uses very low heat and shorter time to produce a milk that is somewhere between raw and pasteurized. It’s not legal anywhere in the US.

The Maine Bureau of Agriculture, Food and Rural Resources inspects and licenses the 87 dairies in the state. The bureau aims to bolster the milk industry.

“We have a [dairy] program and state environment that fosters a lot of support for milk producers,” said Nancy McBrady, director of the bureau. “We want to support these businesses and our philosophy is to work with them and not be heavy handed [and] the industry welcomes that collaboration.”

Still, dairies are not free to run their operations in ways that result in unsanitary products.

“We wear a hat that is regulatory and prioritizes public health and we know we walk a fine line,” said Linda Stahlnecker, director of the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry milk quality laboratory. “We know this is your business but how can we help you make it as clean as possible for people?”

Each licensed dairy in Maine is inspected multiple times throughout the year by a state certified dairy inspector. If a dairy is found to be out of state compliance in any way, Stahlnecker said the Department of Agriculture works with them to solve the problem.

“The state is a partner in my business,” Rector said. “They are 100 percent behind my succeeding and willing to do their part to help me succeed.”

That collaboration and the unique regulations are helping Maine’s cheese industry grow, according to McBrady.

“Those that are using milk to create value-added products are doing well,” McBrady said. “Our cheese industry is growing steadily and there is so much opportunity for that growth with great products.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Eric Rector’s title and how Balfour Farm makes its cheeses.