- Experts say the dairy industry has been draining the life out of Cuatrociénegas, a unique wetland reserve containing bacteria that may explain evolution.

- Farmers in one area say Beta Santa Mónica, Nestlé’s largest Mexican milk supplier, has used fraud and corruption to illegally occupy their land and steal their water.

- They accuse local officials of forging paperwork to help the dairy company, while Mexico’s national water agency turned a blind eye to the over extraction.

OCCRP’s analysis shows Beta may be using as much as 13 times its legal allotment of water to cultivate crops, despite having no licenses in the municipality.

It was more than 20 years ago when Félix Lumbreras first saw with his own eyes that the Churince lagoon was disappearing.

The lagoon was once the largest body of water in Cuatrociénegas, a UNESCO-recognized wetland nestled in a mountain valley in Mexico’s Chihuahuan desert whose name literally means “four marshes.” The last remnant of a prehistoric ocean that vanished as the earth’s continents were forming, Cuatrociénegas is home to unique bacteria that scientists believe hold the key to understanding how life on earth began.

When Lumbreras visited in 2000 to measure water levels in the reserve, he estimated the Churince lagoon had receded seven meters in a year. When he returned seven or eight years later, he found in its place scattered skeletons of endangered turtles, one of 77 species endemic to the oasis. Today all that remains of the lagoon, once a kilometer long, is arid grassland.

“What they did in 20 years won’t be recovered in a hundred,” said Lumbreras. “As we say in Mexico: ‘Mr. Money is a powerful gentleman.’”

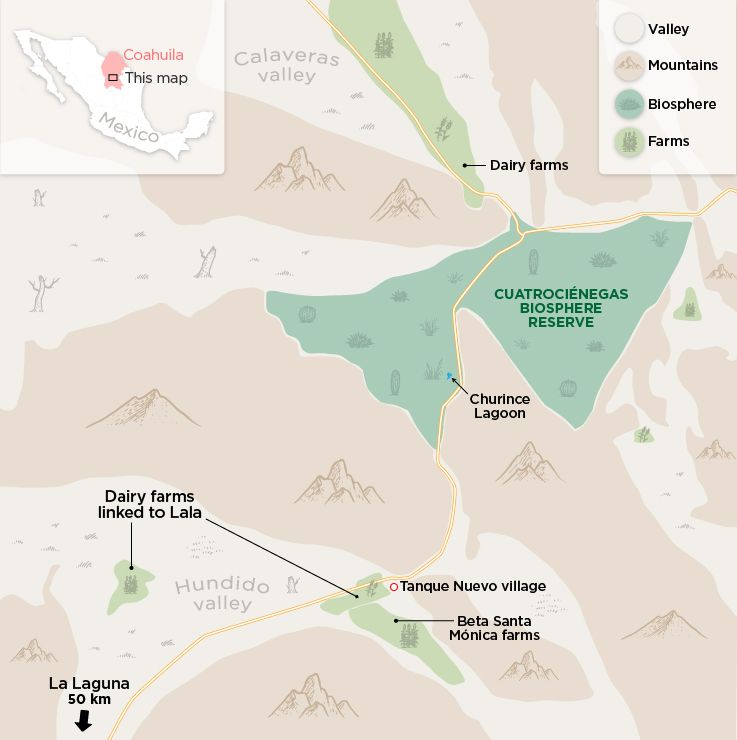

Churince started to disappear after Mexico’s dairy industry arrived in the area in the early 2000s in search of new land to grow cattle feed. Dozens of new wells were drilled in a valley a 15-minute drive south of the lagoon, from which massive amounts of water continue to be pumped out from the ground today.

Scientists fear Cuatrociénegas is on the verge of collapse, bled dry by the vast fields of water-hungry feed crops that now blanket the valley and the many wells and water systems that tap into the aquifer beneath.

“They’re sucking it up from below,” Juan Carlos Ibarra, the protected area’s director, told OCCRP. “There’s ecocide in that place.”

The arrival of dairy companies in Cuatrociénegas has created a climate of lawlessness and corruption around one of the most important ecosystems in the world. Farmers in one area say Beta Santa Mónica, Nestlé’s largest Mexican milk supplier, has illegally occupied their land and stolen their water for close to a decade using fraud, threats, and political corruption.

OCCRP’s analysis shows Beta may be using as much as 13 times its legal allotment of water to cultivate crops, despite having no licenses in the municipality. Not only has Mexico’s national water agency done nothing to prevent such over-extraction, it even appears to frequently act in the dairy industry’s favor.

Neither Beta Santa Mónica nor the national water agency, CONAGUA, responded to multiple requests for comment.

The Cuatrociénegas area in northeastern Mexico.

Milking the Desert Dry

Tanque Nuevo is a dusty village of gravel roads and frequent water shortages. The remnants of an abandoned restaurant greet visitors who occasionally turn off the highway. In the summer, its adobe mud houses bake in searing temperatures that can reach 47 degrees Celsius (116 Fahrenheit.)

Outside the arid town, however, verdant green fields fed by industrial irrigation systems stretch across the Hundido valley to the feet of the surrounding hills.

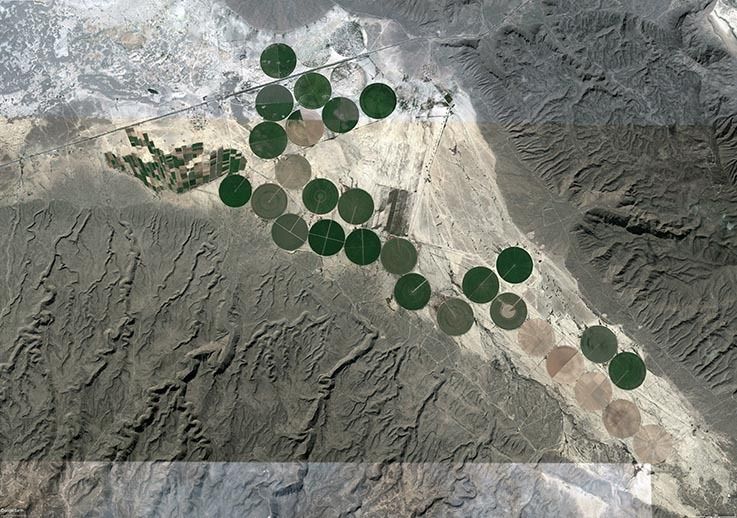

Most of these belong to Beta, which arrived in the valley around the turn of the century. Two decades later, its fields of alfalfa spread so far you can see them from space. But while Beta’s presence in the Hundido valley is undeniable, its legal right to be there is more questionable.

Beta’s lack of proper paperwork first landed the company in trouble not long after it arrived.

In 2002, Mexico’s state environmental protection agency temporarily halted its operations for failing to conduct a legally required environmental impact assessment and illegally using the land for agriculture. Such changes had wiped out endemic plant life across the valley. Beta was ordered to spend 1 million Mexican pesos (the equivalent of US$98,000 at the time) on restoration, compensation, or both.

Earlier that same year, the farmers of Tanque Nuevo allege, the dairy giant started illegally taking over the land they collectively own, using forged paperwork.

Beta uses the land based on agreements struck in a series of community assemblies between 2002 and 2004. Official meeting minutes from the time say the community agreed to transfer portions of its land, along with groundwater extraction licenses, to 11 individuals that included a Beta director, accountant, and engineer.

But five community leaders and farmers from Tanque Nuevo told OCCRP that the meetings never took place. Public records, which the farmers submitted to court as evidence, also show problematic discrepancies, including that the water license transfers didn’t exist in CONAGUA’s national records.

Four community members whose signatures appeared on the paperwork later testified in court they didn’t even know several of the people who they supposedly granted the right to use their land. The signatures, they said, were either faked or coerced.

In later court proceedings, several of the alleged proxies themselves testified that they had received the land lawfully as local residents. Beta, the accused public officials and government agencies all testified that the accusations were baseless and that the transfers were all above board. All insisted that the company had not been involved.

Further trouble arrived in 2004, when the farmers say Beta annexed thousands more hectares of their land by fencing it in. Anyone who tries to set foot inside the area, the farmers say, is swiftly arrested by state police.

“They told us, ‘We’re going to put up a fence so that the animals don’t get in,’” said Enrique Gonzalez, the farmers’ current leader. But once the area was enclosed, the farmers claim that the dairy company laid claim to the land inside the fence.

In 2006, the farmers lodged a legal complaint to reclaim the land they said Beta took illegally. Two years later, an agrarian court ruled in their favor, declaring the original contentious meeting null and void, meaning that all the land and water rights being used by Beta should have returned to their former owners.

That court order has still not been executed. Instead, the farmers have spent the last 13 years fighting to see it enforced through a string of ongoing lawsuits and criminal complaints. The thousands of pages of court documents they have accumulated describe an intricate web of fraud, lies, and power behind the politics of water in Cuatrociénegas.

At a 2018 court hearing, Beta’s legal representative denied knowing of any unlawful possession of the ejidos’ land. The company declined to respond to OCCRP’s questions about the land.

The ejidatarios, or farmers, of Tanque Nuevo have spent 16 years fighting to get their land back.

The farmers allege public officials forged documents to help Beta commit the land theft and later try to kill their lawsuit. All the contested paperwork features the same handful of public officials, including local notaries and representatives of the agrarian agency, which are meant to act in the interest of farmers.

In 2008, a woman who used to work with a lawyer who has represented Beta claimed to have been granted power-of-attorney for the farmers, and quickly withdrew their legal complaint. But the farmers say the paperwork was fraudulent, pointing out that one of the farmers who apparently signed the document is illiterate.

The farmers also highlight a meeting the following year at which they supposedly chose three people to make decisions on their behalf regarding the lawsuit — two of whom then promptly withdrew it. Yet at least two of the people who apparently voted for these representatives were dead at the time, according to death certificates seen by OCCRP.

There were “many forged signatures of ejidatarios who never attended the assemblies” among the paperwork, said Gonzalez. “Even the dead show up.”

The farmers are still fighting to overturn these empowerments today, and say they have been offered bribes to give up. When that didn’t work, they say they received threats. Gonzalez said he now lives in a state of constant fear.

“When a truck arrives, I stop and look first to see whether or not it’s someone I know,” he said. “Sometimes when I go to [the cities of] Saltillo or Torreón, I don’t know if I’ll return alive.”

Running Out of Water

Beta states in promotional material that its water use is environmentally sustainable. But an analysis by OCCRP shows the firm could be extracting anywhere between 3.3 and 13 times its legal allowance.

Beta is licensed to extract 3.5 million cubic meters of water per year under its own name in the entire state of Coahuila, which includes Cuatrociénegas. Companies are also allowed to nominate proxies to extract water. However, even including all known proxies for the company — ones that are named in the farmers’ court case — the maximum the company is allowed to extract is 14 million cubic meters, which must nourish their crops, 28,000 cows, and six million chickens.

Satellite data from the Hundido valley shows Beta irrigates approximately 1,577 hectares of crops. According to Mexico’s agriculture ministry, one hectare of alfalfa needs at least 22,500 cubic meters of water every year, meaning Beta’s fields must require an annual minimum of 47 million cubic meters.

This figure could well be significantly higher. Beta says its Tanque Nuevo ranch produces 240,000 tonnes of fodder each year, most of which is likely alfalfa. A single kilogram of dried alfalfa typically requires about 853 liters of water to produce, meaning Beta’s fodder could be using some 182 million cubic meters of water each year. OCCRP put these figures to Beta but received no response.

“It’s an immense amount,” said Ibarra, the director of the protected nature reserve, who is calling on Mexico’s water agency, CONAGUA, to investigate the true situation in Cuatrociénegas. “I’m swimming against the current.”

But CONAGUA may be part of the problem.

Despite complaints about Beta’s overextraction, CONAGUA has not issued a single sanction against the company since it arrived in the Hundido valley, according to a freedom of information request filed by OCCRP.

The agency’s registry shows Beta does not have a single license under its own name in the municipality, and the ejidatarios of Tanque Nuevo claim that the majority of the 17 wells it controls on their land are illegal. While using proxies is legal, they make it harder to tell if the company is over-extracting and deflects legal liability.

Ibarra said he reports suspicious wells inside the nature reserve, but the water agency does not inform him of whether it takes action. Data released to OCCRP shows that as of early 2021 CONAGUA had sent no inspectors to the municipality for two years, and in the two decades after the dairy firms arrived, it issued just 10 sanctions, none of them for wells inside the nature reserve.

However, Beta’s neighbor, a ranch set up by former Lala executive Florentino Rivero Alonso, was sanctioned twice for operating wells without a license and failing to monitor how much water it was using.

A Matter of National Security

Mexico designated water a national security issue in 2004, yet supplies continue to run short. Nearly 85 percent of the country was in drought this spring and 70 percent of the country is considered at risk of becoming desert.

Conflict over water is also becoming increasingly violent. At least two indigenous water activists have been assassinated in northern states since 2020, one of whom had spoken out against multinational corporations. A third water activist may have been targeted with invasive spyware as he campaigned against a U.S. beer company.

When farmers seized control of a dam in drought-hit Chihuahua in the fall of 2020, the response from the National Guard left a protester dead.

Activists and governmental audits have repeatedly warned that CONAGUA is failing to protect the country’s water supplies, including by approving too many licenses, often to beneficiaries lacking the proper paperwork.

Today, almost a quarter of Mexico’s aquifers are overexploited, meaning new extraction licenses cannot be issued. Water researcher Cuauhtémoc Osorno Córdova said that is exactly when some turn to more clandestine methods.

“[It’s] not only the industrialists and agriculturalists, but many times it’s been the municipal governments themselves,” he said.

One problem is that CONAGUA classifies the aquifers beneath Tanque Nuevo and Cuatrociénegas as distinct, so companies were allowed to extract water from under one but not the other. Ibarra, scientists and activists, however, say these aquifers are both part of one underground body, meaning water pumped out of one place may also drain the protected reserve.

Overextraction has also meant that wells used by locals are yielding lower-quality water, forcing them to dig even more wells.

The decision to classify the aquifers as different bodies of water was made while CONAGUA was led by the former director of Lala, the largest dairy company in Latin America. Cristobal Jaime Jáquez became the agency’s director in 2000, just as Lala and other dairy companies were flocking to the valleys around Cuatrociénegas. His tenure, which lasted until 2006, was plagued by allegations of corruption, including claims that he allowed the dairy industry to destroy the underground aquifers by permitting improprieties.

Jaime wasn’t the only CONAGUA official with a cosy relationship with the dairy industry. Its former state delegate left to become Beta’s defense lawyer in the battle against the farmers of Tanque Nuevo.

Documents seen by OCCRP show another state delegate, José Guillermo Barrios Gutiérrez, was sanctioned repeatedly, including for granting permits in an overexploited aquifer and connections to a harassment campaign.

Activists working to protect Mexico’s water said that the agency has improved in some areas, but that chronic underfunding and dysfunctional bureaucracy have complicated efforts at reform.

“CONAGUA is really a nest of hornets,” said renowned biologist Valeria Souza, who has worked on Cuatrociénegas for decades. “Everybody’s involved in different ways in this web of corruption of the water management.”

The Lost Laguna

The rising tensions over water in Cuatrociénegas reached a boiling point in October 2020, when local farmers attacked environmentalists as they tried to block a decades-old canal that drains water from the reserve. It was work that should have been done by CONAGUA, which has been legally obligated to close the canal since 2010. Its failure to do so left volunteers to step in and put themselves at risk.

Mauricio de la Maza Benignos, who at that time was the director of NGO Pro Natura, said their work was interrupted by a group of locals led by an employee of the mayor’s office who had reportedly threatened them before. The altercation turned violent, leaving de la Maza physically injured.

“They’d already been there for four hours threatening us, hitting us, when the police arrived and grabbed us,” he told OCCRP. “The municipal police said to me that it’d be better for me to leave Cuatrociénegas and never come back.”

“The Lagunera region is a hydraulic society Those who have water have power.”

– Francisco Valdés Perezgasga

Scientist and activist

A few hours’ drive south from Cuatrociénegas lies a region known as La Lagunera. Here, where both Beta and Lala first began their work, vast white plains of cracked earth have replaced a once-thriving lake. What drinking water is left has reportedly been poisoned with toxic levels of arsenic.

Scientist-activist Francisco Valdés Perezgasga said the area was ruined by dairy companies that illegally used water resources, were tipped off to CONAGUA inspections, and even had armed men prevent inspectors from examining illegal wells. As the companies drained the wells, he said, they also sapped local people’s strength.

“The Lagunera region is a hydraulic society,” he said. “Those who have water have power.”

According to information released to OCCRP, one landowner in Cuatrociénegas was sanctioned for refusing entry to the visiting CONAGUA inspector.

Souza, the biologist, said Mexico’s water wars will hurt the poorest the most.

“The rich people will get the deeper wells and have irrigation, and the poor won’t have any. And as always, the poor people have to migrate to more miserable lands,” she said. “Here we know the tragedy is coming.”