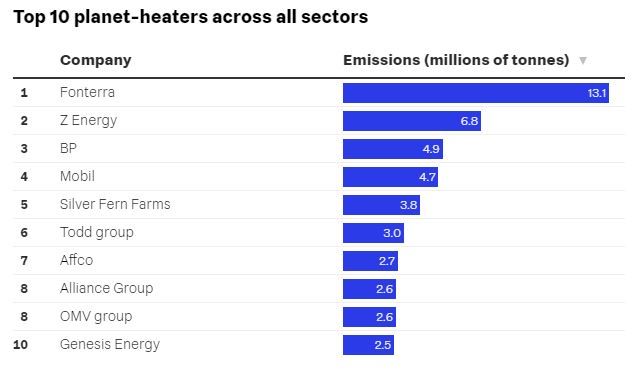

New Zealand’s top 10 emitters still make more than half the country’s greenhouse gases, with Fonterra taking out the top spot for the second year running, followed by the three biggest petrol retailers.

Fuel chains Z Energy, BP and Mobil followed Fonterra, while the fifth spot was taken by red meat processor and exporter Silver Fern Farms.

Rounding out the top 10 were a collection of gas drilling businesses owned by Todd Corporation (which Stuff has grouped together), followed by meat companies Affco and Alliance Group.

Alliance shared 8th spot with Austrian oil giant OMV while Genesis Energy (which operates Huntly’s coal power station) and NZ Steel (which also burns coal, to make steel) came in at 9th and 10th.

The figures are for 2021 and were published by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), using data companies have to supply by law.

While the tallies are sometimes crude estimates, published months after the emissions happened, they are one of the few ways to compare the planet-heating impacts of companies, since several big companies don’t publish their footprints voluntarily. (The EPA lists often cover a different subset of emissions from companies’ own reports, however.)

As in 2020, the biggest tallies were for milk, petrol, fossil (or natural) gas and meat businesses, with electricity and steel companies rounding out the top group because of their fossil fuel use.

By contrast, many of New Zealand’s biggest employers and profit makers (including banks, vineyards, telcos, healthcare companies and renewable energy providers) don’t appear in the top climate polluter ranks because their emissions aren’t high enough to qualify for compulsory reporting.

Source: Environmental Protection Authority

No great progress

New Zealand typically makes a little under 80 million tonnes of emissions a year (though this is slated to fall under climate change measures).

Together, the 10 top-emitting companies account for more than half of that.

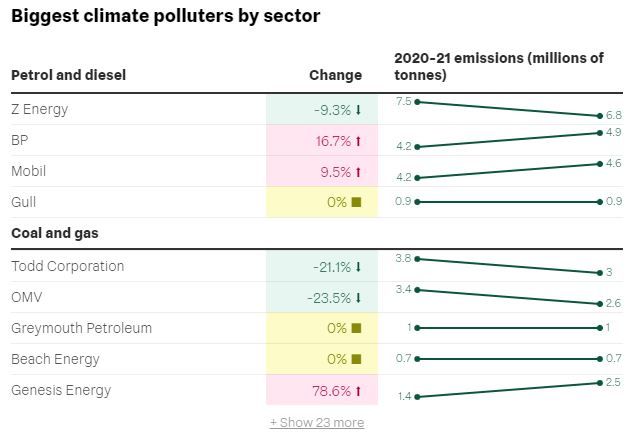

From 2020 to 2021, many of the country’s biggest planet-heaters barely budged their emissions, despite significant cuts being needed to curb rising temperatures.

Z Energy recorded a large drop, however those emissions were largely picked up by BP and Mobil, resulting in little change overall in the collective tallies of the top few petrol companies.

The Todd group of companies and oil giant OMV also produced less emissions year-on-year. The biggest risers included Genesis Energy, whose coal imports rose markedly. Genesis’ coal use has dropped since the figures were gathered, because rain filled the country’s hydro dams and so less coal-fired electricity was needed.

In farming, big agriculture companies such as Fonterra and the large meat exporters changed their impacts little across the two years, though fertiliser companies Ravensdown and Ballance’s greenhouse gas outputs fell.

The report also shows who the emissions minnows are – companies whose impact is smaller than might be expected. For example, all the council landfills together reported lower greenhouse gases than the single 4th-biggest red meat business, and chicken companies such as Tegel and Inghams barely registered in the table compared with red meat and dairy exporters.

How to read the numbers

This is the second time the EPA has published polluter data by company name, under a requirement introduced by Emissions Trading Scheme reforms.

Both the meat industry and the oil and gas drilling industry opposed making the figures public when submitting on the law change.

The report lists the climate pollution, in tonnes, of companies covered by the Emissions Trading Scheme, as well as agriculture (which is required to report but not pay for its emissions of farm-related gases, methane and nitrous oxide.)

All non-CO2 greenhouse gases (including methane, nitrous oxide and others) are converted into carbon dioxide equivalents based on their heating impact over 100 years.

The EPA reports petrol emissions at the point of sale, counting them in the fuel retailers’ tallies.

Where companies are owned by the same parent – for example Kupe Ventures (which is owned by Genesis Energy) and companies in the Todd and OMV groups, Stuff has added their emissions together.

The tally typically captures emissions as far up the chain as possible. For example, coal, gas, petrol and diesel are counted against the tallies of whoever mines, drills for, or imports the fossil fuel to New Zealand – not those who fill up their cars and trucks, or burn gas or coal for their manufacturing.

Likewise, greenhouse gas emissions from rearing and farming animals for meat or milk are counted at the point where the animals or milk are processed, meaning Fonterra, Silver Fern Farms, Alliance Group and Affco appear as major emitters despite most of the emissions coming from their farmer-suppliers.

One exception to that rule is that companies such as NZ Steel, Fonterra and Contact Energy report the gas and coal they purchase in New Zealand under their own tallies, meaning it goes under their names in the list and not under the coal or gas miner.

Although the EPA data doesn’t cover all emissions – because only bigger emitters are captured – it captures more than 280 of the country’s largest petrol, waste, industrial and other companies.

If you live in the red parts of the Northern Hemisphere, then you just completed one of the hottest summers ever measured (based on 3-month average temperature)https://t.co/Swy7jgmlna

In the blue areas it was unusually cool (yes, there is blue on the map). pic.twitter.com/q51pvxH3Vx

— Dr. Robert Rohde (@RARohde) October 8, 2022

Tricky comparison

The EPA tallies can be quite different from the numbers companies put in their annual reports.

For example, companies’ annual reports cover a financial year, whereas the EPA reports cover a calendar year. The EPA reports often use basic estimates based on quantities of products produced, whereas companies may use more refined accounting in their own tallies.

Most importantly, though, voluntary reports by companies often cover a bigger or smaller subset of their climate impact, making the totals hard to compare.

For example, a company’s own emissions report might choose to only cover its own premises and exclude the impacts of its products being used elsewhere by customers (for example, petrol being used in someone’s car or gas being burned in an appliance). The EPA report counts emissions from products such as petrol at the point of import or production, slating the impact home to chains like BP.

On the opposite side of the equation, a company’s own report might voluntarily include the climate impact of its overseas supply chain (such as coal burned by Chinese manufacturers to make goods), but these would not be reported by the EPA because the climate pollution happened outside New Zealand.

Fonterra, for example, voluntarily reports the climate impact of its global supply chain in its own reports but can’t report this to the EPA. Genesis Energy, likewise, reports a larger total in its own greenhouse gas reporting (including business travel and its own energy use, amongst other things) compared to its EPA tally, which just covers the company’s coal importing and gas field production.

Starting this year, about 200 big companies will have to publicly disclose their climate impacts, including some that aren’t covered by the EPA reports. But the new rules still won’t cover big privately-owned emitters, such as Todd Corporation, or overseas-based companies, such as BP, meaning the next EPA report will still be revealing.