He kept his word, but now times have changed.

“I’ve got to make $16 (per 100 pounds, or 11.6 gallons of milk) just to break even,” Dwight Raber said, as he turned the pages on a printed report that details daily production of the farm’s 235 cows. “Right now, I’m at $13.89, and it’s been that way for two years.”

In Raber’s younger days, a cow that produced 100 pounds of milk a day was a herd superstar. These days, that’s almost the average. Large-scale dairy farms and low milk prices have forced Raber to find new ways to keep the bills paid and their farms operating.

Raber added beef cattle to the farm to supplement the dairy portion. But even so, he has come to the conclusion that he just can’t make a living at it anymore.

So, at 10 a.m. Wednesday, Raber will sell his herd of dairy cows and much of the equipment he has accumulated through the years.

The same story is being played out at an increasing pace across Ohio, which lost nearly a quarter of its dairy farms in just over two years. In January 2017, there were 2,647 dairy farms in Ohio, compared to 2,045 by January of this year, according to license statistics from the Ohio Department of Agriculture. The state lost another 51 dairy farms already this year, slicing the statewide number to 1,994.

In addition to the Holstein cows, the Raber sale includes a Jaguar chopper, a six-row folding rotary corn head, a silage table, skid loader, trucks, a tractor, tandem twin manure spreader, disc, hay baler, cultivator, a computerized calf-feeder, milking units and a 3,000-gallon bulk tank, which held milk until it was trucked away daily.

“He has poured his heart into this farm,” said Raber’s wife, Julia, an English teacher at East Canton High School. “He just goes and goes, 24/7. But it’s time to slow down; it really is. His mother also told him, ‘Please don’t ruin your health.’”

***

The trend in dairy farming is alarming, said Dianne Shoemaker, an Ohio State University Extension Field Specialist in dairy product economics. “It’s … not the way I’d like to see the dairy industry going.”

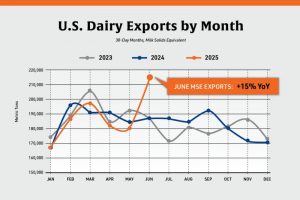

She said the business has changed dramatically in the past 25 years. Profit margins are smaller and smaller, which often requires farms to get even larger to survive. Shoemaker said about 17 percent of the milk produced in the U.S. is exported.

“There’s a lot of milk out there,” she said. “Back in grandfather’s day, the milk prices were local. Now they are global … or they are at least influenced on a global level.”

Dairy farmers enjoyed a boom year in 2014, but it has been bad four years in a row, Shoemaker said, adding that the plight of Ohio farmers is partly due to a glut of milk coming into the state from megafarms in Michigan — often at less than market rate.

Farming is all Raber has known. He’s accustomed to working long hours, waking up at 4:15 a.m. and quitting at sunset, but that lifestyle has become ever more grueling now that he’s 58 years old. The stress of keeping his farm afloat took its toll, and he was hospitalized with blood clots last summer.

Raber and his brother, Bruce, who died in 2007, grew up working the farm. So did his father, Russell. Same for his grandfather Ernest. And his great-grandfather Albert, who founded the farm after he came to the U.S. from Switzerland in 1891 and changed the family’s surname from Reber to Raber because he grew tired of hearing it being mispronounced.

“I’m a little scared,” Raber admitted.

Over the years, the farm grew to its present 500 acres.

Dwight and Julia Raber’s two natural-born sons, Alan and Scott, helped for years on the farm. But ultimately, they chose other careers: Alan is a Stark County Sheriff’s deputy, and Scott manages Titan Machinery stores in Nebraska.

“We never tried to push them into farming,” Dwight said. “We let them find their way. … I remember when I was a kid, I played sports in high school. And after the games, my friends would say they were going home to sleep or do whatever. But I’d just go home and work for four hours. It’s just what we did.”

Dwight and Juliahave three other sons — all adopted as young boys from Russian orphanages: Aaron, 20, Isaac, 18, and Austin, 15.

***

Dairy cows get milked twice a day. They’re also particular about their feed. Their mix has be consistent and exact in order for them to produce milk at a high level.

Beef cattle are less high-maintenance.

Raber said he’ll take advantage of his extra time to tidy up the property and pay more attention to aesthetics, as his mom and grandmother did.

“This was a showplace; I want to return it to that,” he said.

Raber smiled and shook his head as he walked by a series of cow hoof indentations in the wet grass near the farmhouse — evidence of a recent “jail break” by some in the herd.

“We’ve been so blessed for so long, and with our wonderful sons … but it’s time,” Julia Raber said of the upcoming auction. “There’s such a beauty about the land. It’s spiritual.”

After Dwight’s mom died a decade ago, her ashes were scattered in a small garden she tended behind the farmhouse. A plaque marks the location. Julia Raber is sure Lela, the matriarch who’d kept the farm going for so long, would understand and approve of the auction.

After all, the Rabers still have the farm, even if it will change.