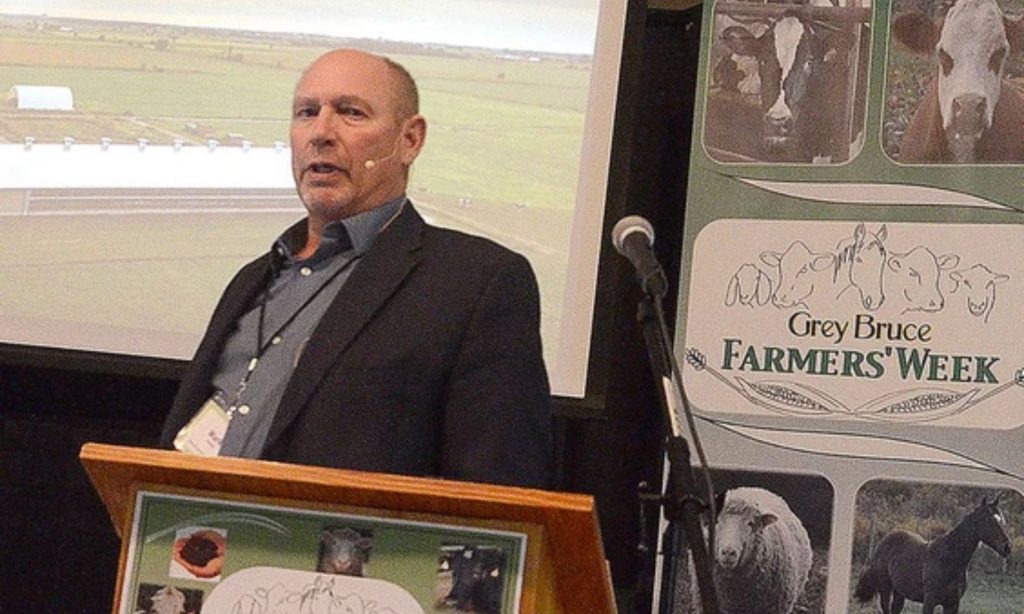

The issue was top of mind during Dairy Day at Grey Bruce Farmers’ Week on Jan. 5. DFO board member Mark Hamel admitted the organization was unprepared for such a large-scale emergency. He also said the organization could have communicated better with producers.

Hamel said he and others at DFO – which buys all milk in Ontario and handles its transportation, processing, pasteurization and distribution – take responsibility for how the crisis was handled. The DFO has made the decision to spread the losses from the dumping across its more than 3,300 members through a compensation and cost recovery plan.

“We didn’t have a good crisis emergency plan in place,” Hamel said. “I will take ownership of that – not all of it, but my share of it. We didn’t have a strategy in place.”

Hamel, who represents DFO Region 11 consisting of Grey and Bruce counties, said the DFO has a strategy in place for handling situations like skimming milk overproduction. In the spring of 2020, for example, dairy farmers in the province and across Canada dumped milk on a rotating basis after demand dropped significantly when COVID-19 shutdowns forced restaurants to close.

But Hamel said the policy in place wasn’t set up to deal with what forecasters were warning would be a “generational storm.”

What hit Ontario over the Christmas weekend – with extensive road closures between Dec. 23 and 26 – was widespread in the number of producers impacted and milk dumped in a short period.

Hamel said almost 45 per cent of Ontario’s producers were affected by the storm. In late December, producers took to social media and showed their milk being dumped. Some farmers, who have limited capacity to store milk as their cows keep producing the perishable product, reported losses in the thousands of dollars. Many had never had to dump milk before, the DFO said.

Paul Vickers, a dairy farmer from Meaford, was vocal in his frustration of the approach taken by the DFO and how it had decided to waver from its usual policy in dealing with the situation. He said he isn’t worried about the dollars lost, but what he called a “swirl of governance” within DFO.

“I will be honest with you, I have dumped milk other years and nobody has really given it a second thought or a second glance,” Vickers said. “Why is it any different when one or two, or a few people do it, as opposed to a larger per cent of the producers?”

DFO chair Murray Sherk sent a letter to producers in early January outlining the organization’s plans to pool the financial losses of missed pick-ups among all producers, not just those who were forced to dump milk when trucks couldn’t get through.

Hamel said the direction from DFO this time was not a policy change but a one-time directive in a unique situation. Hamel said the DFO’s current policy for dumping milk is still in place, and has worked well in the past.

“We have tried to do a better job in the past and clearly we didn’t do a good enough job this time,” he said. “We are taking that away and we are going to try and correct the situation, make sure we have better emergency and crisis situations in place clearly documented to producers, transports and the processors.”

Producers who had to dump their milk will be compensated for their loss, while the DFO is covering the loss through an expected reduction to the milk blend price of about $2.50 per hectolitre. Hamel said the reduction would be in place for a month, adding that lower demand during the holiday season would have decreased the price by $1 to $1.50 per hectolitre even without the storm.

The DFO has said consumers are unlikely to see any impact from the situation.