Westland is a small dairy co-op but a big cautionary tale for our entire economy, not just the primary sector or narrowly dairying or even just co-ops. It shows how incredibly hard it is for a small commodity producing country like ours to move up global value chains to niches of greater value and market power. Astute strategies, excellent execution and diligent governance are required every step, every day.

And when we sometimes fail, it is often massive, well-resourced overseas companies that out-bid New Zealand companies for the valuable assets. Often, they already have the direct access to consumers at the top of the value chain which makes them dominant.

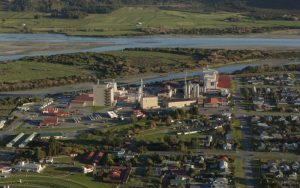

This is the case with Westland. On Thursday, its 429 farmer-shareholders will vote on whether to sell their co-op to Yili, the largest dairy company in China and Asia. It is the only viable option they have left after the co-op’s decade and a half of rapid expansion. In many ways the growth was good. But some long running bad decisions about capital management and strategy have cost the co-op its independence.

The $588 million deal makes sense for the farmer-owners in the short and medium term. They will receive $3.41 a share for their equity. Grant Samuel has valued it at $63.3 million to $99.7 million, compared with Yili’s $246 million offer, with the rest of the $342 million purchase price being the assumption of Westland’s liabilities and its excessive debt.

And Yili is promising to at least match Fonterra’s milk payout for the next decade, a welcome relief to farmers after Westland’s consistent under-performance against Fonterra in recent years because of its higher overheads and debt.

There’s no knowing whether Yili will pay more than Fonterra in years to come. It could if it was smart, and if it wanted to it could. It has invested $650 million in New Zealand since 2013 buying and expanding Oceania Dairy, a south Canterbury processor. If Westland accepts its offer, Yili’s investment here will hit $1.2 billion, slightly exceeding Fonterra’s investment in China in Beingmate, the troubled infant formula company, and farms.

Scale for a big ‘Kiwi’ brand

Oceania plus Westland would give Yili a big enough milk supply and production base to create a high-end, NZ-based brand under which to sell NZ dairy products to discerning consumers in China. If it succeeds, it could afford to pay its suppliers more than Fonterra pays because Yili controls its value and supply chain right to many of its customers, capturing value all the way up. Treating suppliers very well would guarantee their loyalty and innovation.

Of course, Yili could decide instead to maximise its profits here by only paying New Zealand farmers enough to stop them switching to competing processors. West Coast farmers would be particularly vulnerable to low payouts. It seems highly unlikely a competing large scale processor would invest there, given the efficiency challenge of collecting milk down the very long, thin coast.

Theoretically, a few premium, boutique dairy processors might set up on the coast over time to play to its magnificent natural environment. But they would need only groups of nearby suppliers. It’s hard to imagine Yili facing competition on much of the coast.

Fonterra couldn’t buy Westland

The opportunity for a New Zealand solution to Westland’s woes are long past. A few years ago, it might have sold some assets, most likely its Canterbury ones, to reduce its debt. But retreating to the West Coast would have only exacerbated its geographic limitations. Or, it might have found a joint-venture partner from home or abroad to increase its capital base, share the risks, increase its opportunities and maintain partial independence.

Being taken over by another dairy co-op was out of the question. Fonterra was the only candidate. But it has plenty of challenges of its own, thanks to its ill-considered and badly executed $1 billion investment in China. That has squandered its scarce equity capital, and increased its debt. Those in turn have forced changes of leadership, culture and strategy, and asset sales.

In essence, Fonterra has made some of the same mistakes as Westland. But, thankfully it has enough scale, skills and resources to dig itself out of its troubles. However, it might well have to bring in some external capital if it is to fulfil its potential.

Even if Fonterra was in better shape and willing to take on the Westland challenge, a merger was out of the question because of a disastrous capital decision Westland’s board made in their deep conservatism years ago. It has long kept its share price artificially low, currently at $1.40 a share, which is a fraction of Fonterra’s. Since shareholder-suppliers have to have shareholdings in proportion to the volume of milk they want processed each season, it was far cheaper to join Westland than Fonterra.

An equity-lite expansion

But that meant Westland raised far less equity capital than it could have to fund its expansion, thereby making it far more reliant on debt; and if Westland was to merge with Fonterra, its farmers would have to invest in its higher-priced shares. Many of them could not afford to, given the financial strains caused by Westland’s lower payouts.

It’s no surprise that the banks that have debt funded the rapid growth of dairying on the West Coast are among the most enthusiastic supporters of selling out to Yili. Some farmers are so strapped they can’t put their farms on the market for fear of losing much of their equity. They live on the forbearance of their banks, which are being careful to ensure an excessive number of farms for sale don’t depress the price.

ANZ, a big dairy farm lender on the Coast, stated in late May that the Yili offer was a “timely cash injection” for farmers who have struggled to recover losses incurred because Westland’s milk price lagged behind other dairy companies.

In other words, Yili is not only getting Westland’s shareholders off the hook, but also ANZ and the other banks they’ve borrowed from.

Yili helping ANZ too

ANZ went on to say that the deal was good for the economy of the West Coast, given dairy farming and processing accounts for some 14 percent of its economic activity. But that’s a rather unintelligent view of our economic potential. Yes, farmers get paid for their raw milk, and Yili’s workers get paid for their labour, and those locals in turn spend some of their money in their communities.

But by far the bulk of the wealth ultimately generated by that milk accrues to Yili and its shareholders and employees overseas. Yili’s offer is the best Westland shareholders can get. Yet such foreign ownership is absolutely not the best model for our entire dairy or primary sector, or the economy at large. We have to have the skills and capital to build up our own ownership of businesses that can push far up the value chain globally to where the real rewards lie.

That’s why Westland’s recent history is so important to understand and learn from. Back in 2001, when our dairy sector amalgamated to create Fonterra, Westland and Tatua were the only two co-ops, both small, that decided to go it alone. Waikato-based Tatua was in the heart of dairy country and was already moving away from commodity products. Its progressive culture and financial discipline have driven its subsequent growth and success.

But Westland began its independent life with three big disadvantages: its geographic isolation on the West Coast which, for example, increased transport and other costs; its commodity focus; and its conservative culture.

Over the subsequent 17 years it has substantially improved itself. It has strongly expanded its supplier base on the West Coast and over the mountains in Canterbury. It has expanded its milk collection by 34 percent just in the past seven years alone; it has invested in plant and overseas markets to move into higher value products such as infant formula; it has developed a full range of corporate functions it needs as an independent company, which it didn’t need when it was a small co-op dependent on the Dairy Board for marketing and innovation.

These days, for example, it has an office in Shanghai with some 20 staff to help handle its sales in China which were worth $118 million in 2018. This was its largest overseas market accounting for some 17 percent of its revenues that year.

Westland’s two big, bad decisions

But that admirable progress has cost Westland its independence because of two big, bad, decisions it made over the years – the capital one, and its decisions not to pursue its early lead in A2 milk. For excellent analysis of this please read this piece by Keith Woodford, the highly respected dairy sector consultant and researcher who had worked closely with Westland.

This is not just a dairy sector story.

Westland and Fonterra’s travails offer crucial lessons about governance, culture and strategy that apply widely across our economy. If we truly want to build and own a high value, resilient economy, we need to learn and apply them with every step, every day.

#Rod Oram investigates the political, economic, and business spheres in New Zealand.