In other words, they are on the lookout for fake cheese.

“This looks like the fishiest thing ever,” one of the food investigators, Domenico Vona, said this month after some Internet sleuthing led him to an “Italian parmesan” made in Ukraine.

Vona studied the product details of the deep yellow vacuum-packed hunks.

“This is blatant,” he said as he filed a complaint to the online marketplace, Alibaba, where it was being sold. “This is definitely not Parmigiano.”

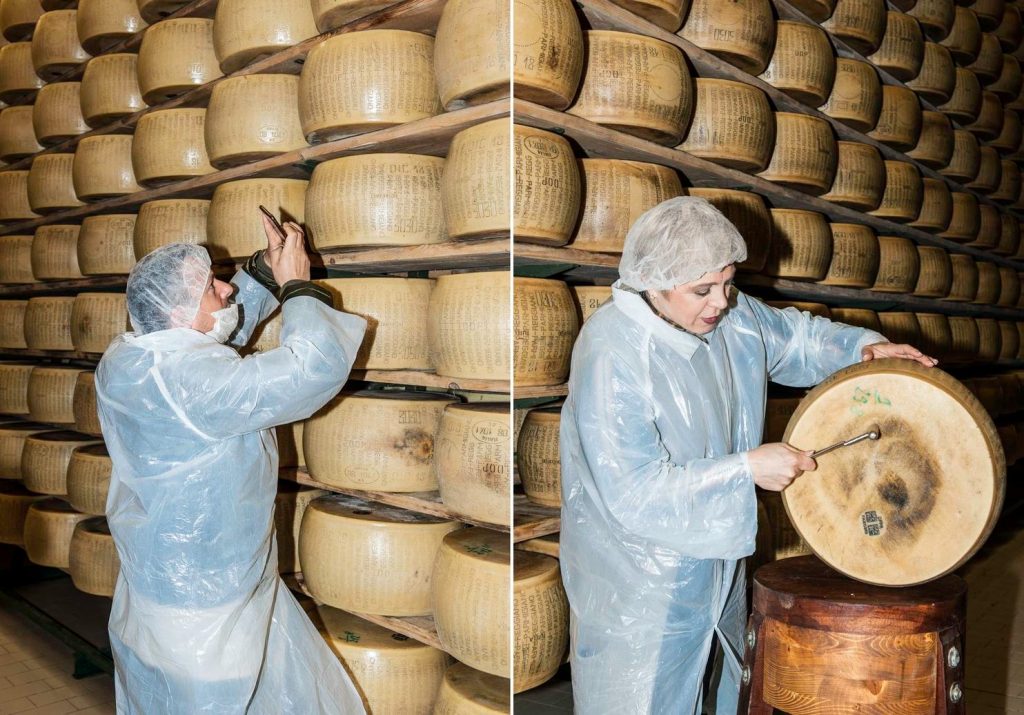

If Italy had its way, there would be no such thing as Ukrainian parmesan. Or American parmesan. In fact, there would be no generic parmesan whatsoever — only Parmigiano-Reggiano, produced inside a small patch of Italian countryside, under exacting specifications, at one of 330 dairies whose cheese wheels are tested with percussion hammers and then branded with markings of authenticity if they pass muster.

Italy is doing what it can to reclaim its signature cheese, as well as other mimicked food and alcohol products, in a campaign combining old food traditions and some new nationalistic sentiment.

In Brussels, Italian diplomats are pressing the European Union to protect Italian foods in trade deals being negotiated with other nations. In Rome, the government team of self-described food cops is signing agreements with online marketplaces to crack down on the Internet sale of faux Italian wines, sausages, cheeses, among others. And the country’s populist leaders — with their “Italians First” slogans — are bashing “Made in Italy” food knockoffs while extolling the greatness of Italian cuisine.

“I want a tricolor flag — big like this — on Italian products,” said Italy’s most powerful politician, far-right League party leader Matteo Salvini, who regularly touts his all-Italian diet on social media.

Within the European Union, foods and wines linked historically to a particular region are categorized as “geographical origin” products. And they are fiercely protected inside of the bloc. The sale of generic parmesan, for instance, is banned in Europe. Other foods with European protection include Asiago, Roquefort, Morbier, the ham called Prosciutto di Parma, and Grana Padano, a Parmigiano cousin. When hashing out trade deals, Europe has tried to press other countries to apply a version of those protections.

But in the many places where European rules don’t apply, parmesan has become the perfect emblem for the debate over whether a nationally significant food can and should be appropriated, and even tweaked, by foreigners. Parmigiano-Reggiano is trademarked in the United States and most other countries, and the term cannot be used for non-Italian cheese. With parmesan, though, producers have nothing stopping them.

“While [our parmesan] is not exactly the same, it’s very similar,” said Jeff Schwager, the president of Sartori, an artisanal Wisconsin-based company founded in 1939 by Italian immigrants. “We intentionally produce ours where the cheese is a little creamier.”

He said the farmland of Wisconsin isn’t so different from that in Italy.

Much of the cheese-loving world says Italy is refusing to let food culture evolve. You might need healthy cows and good workers to make delicious parmesan, they say, but you don’t need Italian soil.

Italians, though, say their defense of Parmigiano is rooted in a mix of good taste, economics and sense that they are upholding culinary commandments. The consortium that regulates domestic Parmigiano production estimates Italy is losing billions of euros because of “counterfeits.” Dairy farmers and producers here worry that foreigners have gotten accustomed to weaker-tasting, imitation parmesan — and could lose faith in a cheese whose name means, literally, “From Parma.”

Agriculture Minister Gian Marco Centinaio, a member of the League, told The Washington Post that Italian and Japanese foods “are the most copied in the world,” and, as a result, Italy has 100 billion “potential frauds we need to attack.”

“Those are markets where we could place our original products,” Centinaio said. “The problem is vast and we are surrounded. In some cases, it feels like we are in Fort Alamo.”

Some of the work of finding those so-called frauds takes place in Rome, in a government building decorated with idyllic paintings of hay and pastures. The Central Inspectorate for Fraud Repression and Quality Protection has been around for several decades, but Italy’s populist leaders recently boosted its budget.

“Food, for us, is a strategic asset,” the agency’s director, Stefano Vaccari, said.

Parmigiano-Reggiano is produced in a flat northern strip of provinces that gave the cheese its name: One of the provinces is Parma. Another is Reggio. The region’s politics traditionally lean slightly to the left, but its food rules are ultraconservative. Beyond the approved zone for Parmigiano-making — an area that includes five provinces, bounded by two rivers — the cheese cannot be made. Within the zone, the cheese can be made only one way: by following rules — created by a consortium of producers — governing cow diet, milk temperature, fat content, even the dimensions of the finished cheese wheel.

The production of Parmigiano moves at a nonindustrial pace because there is no other way. The cheese is churned in copper vats — by rule, of course — that must re-oxidize after use, meaning the vats typically remain unused for roughly three quarters of the day. As a result, there is almost no round-the-clock Parmigiano production. The process is hushed, deliberate. One typical company, Bertinelli, has three workers who make cheese every day from 10 vats that look like overturned church bells. They use cheese cloths, wooden sticks and their hands.

“You expect a factory to be sterile, almost like a hospital,” said Ilaria Bertinelli, the daughter of the company’s founder. “But it’s not.”

A visitor to the region might quickly hear about how the Parmigiano process has changed little over nine centuries, or about customs documents showing the exporting of an ancestral Parmigiano cheese during Medieval times. Cheese makers are aghast at the suggestion that the formula for Parmigiano might possibly be altered for the better; in fact, if it changes, they say, the cheese is no longer Parmigiano.

But in some other ways, production is changing. Fewer Italians are performing the cheesemaking jobs, which pay well but require early wake-ups and heavy lifting. Bertinelli’s workforce consists of one Italian-born “cheese master” and two assistants, a married couple from the Ivory Coast. One of those workers, Mamadou Diawara, said he relishes a stable job but doesn’t love parmesan. “I like softer cheeses,” he said. “French cheeses.”

In 2016, Cook’s Illustrated, the American culinary magazine, oversaw a test in which 21 tasters sampled five kinds of parmesan and two kinds of Parmigiano. The American cheeses tended to be “rubbery and bland,” the magazine said, compared to the more pleasing Italian cheeses, which were fattier and less salty. But one of the American parmesans was quite tasty, and even had the trademark “crystalline flecks.”

“If domestic producers — or producers anywhere — were to follow more of the Parmigiano-Reggiano specifications, we think they could make a comparable cheese,” the magazine wrote.

Italians are dubious of that claim.

When the leaders of the Parmigiano-Reggiano consortium visited New York last year for a food convention, they used the downtime as they often do on foreign visits: to conduct a test of their own. They went to supermarkets and bodegas across the city, buying up whatever parmesan they could find, and they returned to northern Italy with a suitcase full of samples.

They retreated to a laboratory to study some of the harder-to-spot variables. But they also smelled the cheese, broke it apart, tasted it.

Consortium director Riccardo Deserti said the American parmesan lacked the complexity and couldn’t compare with the original. He had a suggestion about what to call it.

“A cheese,” he said. “Simply, a cheese.”