Those cheese prices are now over $2.50, and Class III milk is $21 — leaving some folks contentedly scratching their heads.

But dairy producers shouldn’t become complacent. Markets correct, and they correct quickly, Sara Dorland, economist with Ceres Dairy Risk Management, said in a webinar sponsored by Compeer Financial.

“Today it feels like there’s simply not enough cheese to be had. All of a sudden there will be,” she said.

It was a perfect storm of events that caused markets to correct and likely overcorrect, she said.

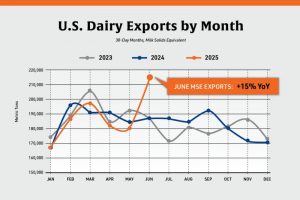

The downturn in restaurant demand led the industry to take corrective actions. Processors and dairy cooperatives put plans in place to limit their milk supply. Milk was being dumped, and culling picked up in some parts of the country. U.S. cheese companies also took advantage of low cheese prices to export a lot of product.

In addition, people got sick of cooking by May and started ordering take-out, delivery and buying food online. The worst period was the end of April and first of May, when USDA decided to allocate funds for the food baskets program under the CARES Act, she said.

“We needed some help. Unfortunately, USDA made the evaluation off of that finite amount of time but didn’t take into account the countermeasures that had gone into place,” she said.

The little bit of needed grease in the wheels ended up being a gusher, she said.

“What we ended up seeing was a tremendous amount of demand coming into the system in a very short amount of time,” she said.

The perfect storm of demand is now a signal to dairy producers to bring on as much milk as they possibly can, she said.

While production is likely to maintain through the hot, humid summer, that milk is going to show up later this year, she said.

“I’m pretty darn certain that every time I see $20 milk, I see farms add cows and grow milk supply,” she said.

She expects the same in Europe and Oceania, raising more concern.

“All of the farms across the globe are being told, ‘We need more milk and we need it now,’” she said.

U.S. exports of nonfat dry milk powder should be positive due to competitive pricing. But with high cheese prices, she doesn’t expect any new commitments.

U.S. dairy is going to have to find some level of demand this fall, and there will be things working against that. Jobless claims continue to rise, there’s some uncertainty in the economy and struggling food service outlets are paying really high prices for cheese, which could lead to fewer promotions.

In addition, the pandemic will likely cause stops and starts to businesses and could resurge, she said.

Schools restocking supply lines should support cheese prices, however, and they could stay stubbornly high longer than people are anticipating, she said.