On a cold March afternoon in southeastern Minnesota’s Driftless Area, Casey O’Reilly sent his three sons to coax the cows into the milking parlor.

It didn’t take much.

“This one’s always first up,” Carsyn O’Reilly, 17, said, nodding toward a Holstein standing in the entryway. “She knows her spot.”

One by one, the dairy cows lumbered into stalls as the teenage sons sprayed orange disinfectant on the udders. Everyone — including Casey’s wife — helped out.

“I’ve got a real job, too,” Kim O’Reilly, who works as a banker in town and grew up on a Wisconsin dairy farm, said. “On top of this one, that is.”

She knows they’re one of the lucky ones.

Organic dairies embody the imagination of yesteryear’s farms. Black-and-white cows feed on green pasture in the summer. Sons and daughters return from school to lift pails of feed or bottle-feed calves. Farms average, maybe, 100 cows — not 1,000.

And the system works because consumers pay steeply for what they believe is a premium milk or cheese or yogurt.

But in 2022, organic farmers were tested, perhaps like never before, under the weight of skyrocketing feed prices.

In January, after lobbying from the organic industry, the Biden administration announced $100 million in market assistance to eligible small and medium-sized organic dairy farms. But as winter turns to spring, the payments have not arrived. And the thinning margins have left some wondering about the once-unthinkable alternative.

“We’ve been organic forever,” said Casey O’Reilly, when asked if he’d ever consider leaving farming. “It’s the only way I’ve ever done it.”

The dilemma of getting bigger

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has regulated organic milk since the early 2000s. But the commercial industry really took off in the 1980s.

The rules are relatively straightforward. Cows — when pasture is available — should eat grass or forage. When pasture isn’t available, they need to feed on organically grown grain, such as soybeans or corn grown without pesticides or herbicides.

While organic milk represents a sliver of the overall milk sector, it’s still a sizable market with a commercial value of $22 billion in 2021. For over a decade, supermarkets across the country have carried national brands such as Horizon, Stonyfield Farm and La Fargo, Wis. based Organic Valley.

When Organic Valley, a cooperative, expanded into Minnesota in the early 1990s, milk from Casey O’Reilly’s farm was on the very first truckload of the company’s milk produced in the state.

Today, O’Reilly and his family milk 95 cows. The average head-per-herd for Organic Valley suppliers is 75 cows. Compare this to the average conventional American dairy head count that exceeds 300. Out west, the herds grow larger. New Mexico, for example, averages over 2,700 cows per farm.

But while organic farmers are often attracted to this smaller scale, it can also be their limitation.

As consolidation racked the conventional dairy industry (with half the nation’s dairies closed between 2003 and 2020), many conventional dairies survived by getting bigger, purchasing more feed and milking more cows.

But scaling up is more difficult in the world of organics.

Adam Warthesen, government relations director for Organic Valley, described organic farming as “scale-neutral.”

“(Organics) doesn’t prohibit anybody from getting as big as they want to get,” Warthesen said in a February interview. But he acknowledged the dilemma for farms caught between growth and their sustainability mission.

“Our co-op?” said Warthesen. “We’re interested in supporting rural communities.”

Last year, those small-scale dairies were more vulnerable to price spikes triggered by events halfway around the world.

The trouble with organic soybeans

Days after Russia invaded neighboring Ukraine at the behest of Russian President Vladimir Putin, prices on the world grain markets shot up amid fears that a blockade of vital Black Sea ports would cause a shortage of wheat, corn and soybeans around the globe.

By May, citing unfair trade practices, the U.S. moved to block organic grain shipments from India, another key exporter of organic meal.

While corn farmers in Iowa and Illinois benefited by fetching higher prices, livestock producers and dairies nervously watched the price of their animals’ feed balloon.

By July, the price on organic soybeans hit $35 a bushel.

“We hadn’t really seen prices that high for a while, if ever,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison dairy researcher Charles Nicholson, an associate professor of animal and dairy sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

On the O’Reilly dairy nestled between Goodhue and Red Wing, Casey said a truckload of soybean meal he bought to last six months cost him $46,000. He’d typically spent $30,000.

The sticker-shock was the latest blow to the dairy farming community, which has grown accustomed to watching peers exit the business. “There’s one that got out

a few years ago. His son just didn’t want to milk anymore and he was getting too old,” said O’Reilly, counting his neighbors who’ve left the industry. “One didn’t have any boys who wanted to take over the farm, so he sold the whole farm. But there’s not a lot in that next generation.”

Over the winter, soybean prices have stabilized. But the pressures the organic milk industry faces are rippling to the storefront.

Milk sales in a time of inflation

The St. Peter Food Co-op in St. Peter, Minn., has long been a harbor for organic and natural foods on Hwy. 169 in south-central Minnesota. But the co-op’s general manager, Erik Larson, said the inflation seen over the last year has dampened sales of Organic Valley products.

“We’re seeing this trade down,” Larson said. “People are getting caught in the pocket book with inflation and saying, ‘Well, I’ll just drink conventional milk this week.'”

Larson cautioned against drawing too many conclusions about consumer spending, observing that his receipts suggest demand for Crystal Ball Farms, a single-herd milk producer in western Wisconsin, have soared by over 60% over the last year.

But he only needs to look at his own kitchen to see what’s happening. He keeps a jug of Organic Valley in the fridge. But he keeps jugs of conventional milk for his sons.

“When a teenager is going to eat three bowls of cereal in a day, they’re going to get conventional milk,” Larson said.

Organic Valley’s Warthesen described consumers’ interest in organic milk as elastic — industry parlance for a drop in consumer demand when prices go up. “We just didn’t have the ability to walk prices up that high during inflationary periods and not see huge consumer drop-off,” he said.

It’s an industrywide squeeze.

In January, French dairy giant Danone, which owns Horizon, put the company up for sale, saying that while the brand remained strong, its earnings “diluted” higher-priority lines.

Then there is the problem of oversupply. Even before the pandemic, the nation had a glut of organic milk. When producers saw lower prices, they instinctively sought to produce more, worsening the oversupply, said Britt Lundgren, Stonyfield’s director of in western Wisconsin, have soared by over 60% over the last year.

But he only needs to look at his own kitchen to see what’s happening. He keeps a jug of Organic Valley in the fridge. But he keeps jugs of conventional milk for his sons.

“When a teenager is going to eat three bowls of cereal in a day, they’re going to get conventional milk,” Larson said.

Organic Valley’s Warthesen described consumers’ interest in organic milk as elastic — industry parlance for a drop in consumer demand when prices go up. “We just didn’t have the ability to walk prices up that high during inflationary periods and not see huge consumer drop-off,” he said.

It’s an industrywide squeeze.

In January, French dairy giant Danone, which owns Horizon, put the company up for sale, saying that while the brand remained strong, its earnings “diluted” higher-priority lines.

Then there is the problem of oversupply. Even before the pandemic, the nation had a glut of organic milk. When producers saw lower prices, they instinctively sought to produce more, worsening the oversupply, said Britt Lundgren, Stonyfield’s director of Organic and Sustainable Agriculture.

“We have these specific circumstances that are in organic supply chain that are driving a problem,” Lundgren said.

Future for organic dairy

Dairy farming is a relatively tightknit community — and organic dairy is even tighter. Of the 2,600 dairies in Minnesota, only 104 are certified organic — 10 fewer than a decade ago.

But in pockets of the country, such as southeastern Minnesota, where fluid milk tankers run winding country roads and cheese factories sit in valleys, optimism remains.

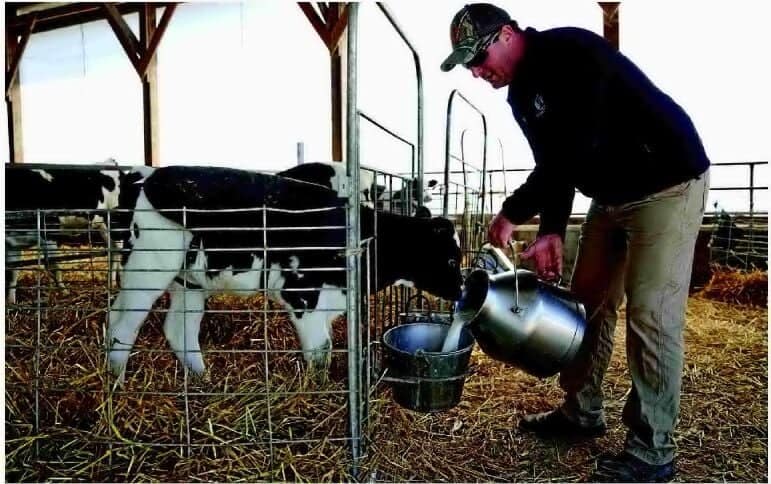

Amid the hard times, Kim O’Reilly tries to focus on the benefits of the family farm. “We’re blessed,” she said, as she bottle-fed a two-day old calf.

The O’Reilly boys brought another 16 cows into their 8-by-8 stalls. Casey marveled that, for some reason, they still wanted to follow their dad into the organics business.

And then he grabbed a hose dangling behind the legs of a cow, hoping to finish milking before sunset.