As highly pathogenic avian influenza has spread in dairy herds across the U.S., a new study led by a broad team of researchers at Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine helps explain why.

As highly pathogenic avian influenza has spread in dairy herds across the U.S., a new study led by a broad team of researchers at Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine helps explain why.

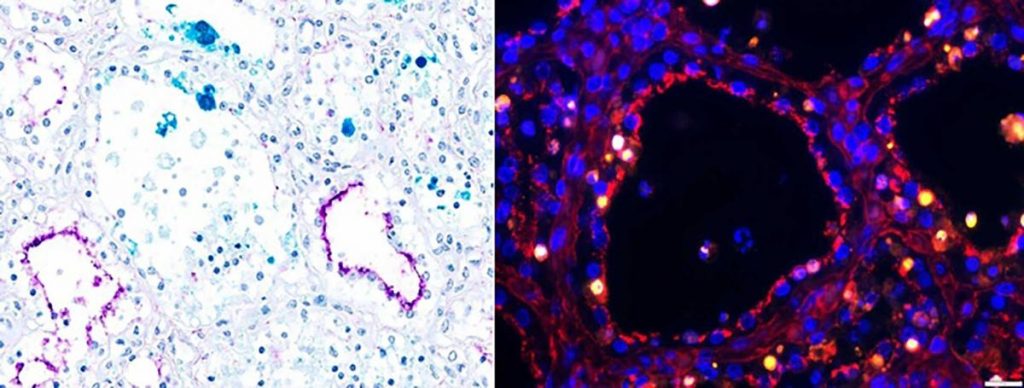

Sialic acid, a sugar molecule found on the surface of some animal cells, acts as a receptor for influenza. Without sialic acid providing an entry point to attach, a flu virus is unlikely to find a potential host hospitable.

Before the recent HPAI outbreak in dairy herds, there was scant research into sialic acid levels in the mammary glands of cattle. Scientists had no reason to suspect the milk-producing organs would be a good target for influenza.

“In livestock, we hadn’t usually looked in milk for viruses. Bacteria, sure. But not so much viruses,” Eric Burrough, professor of veterinary diagnostic and production animal medicine, said in a university news release.

“The idea that the mammary glands are being passively infected is put to rest by this paper,” he said. “They’re pumping out tons of virus and that’s a risk.”

The infected dairy cattle samples ISU researchers examined — both mammary glands and respiratory tissues — had receptors for flu strains that originate from birds as well as humans and pigs.

The presence of both types of receptors poses added risks, as a single cell infected by avian and mammalian viruses could lead to potentially dangerous mutations, Bell said.

The study was published in the July edition of Emerging Infectious Diseases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s peer-reviewed journal.

Another article in the same edition of Emerging Infectious Diseases describes the initial diagnosis of HPAI in dairy, a finding made at the ISU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory this spring.

Speedy teamwork in the face of new public health threats is essential, said Rahul Nelli, research assistant professor of veterinary diagnostic and production animal medicine.

“Having different departments coming together to collaborate was key for this study and will be key for future investigations,” Nelli said.

Further research could involve influenza receptors in other species and organs, including a closer look at dairy cattle, Bell said.

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K

Legal notice about Intellectual Property in digital contents. All information contained in these pages that is NOT owned by eDairy News and is NOT considered “public domain” by legal regulations, are registered trademarks of their respective owners and recognized by our company as such. The publication on the eDairy News website is made for the purpose of gathering information, respecting the rules contained in the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works; in Law 11.723 and other applicable rules. Any claim arising from the information contained in the eDairy News website shall be subject to the jurisdiction of the Ordinary Courts of the First Judicial District of the Province of Córdoba, Argentina, with seat in the City of Córdoba, excluding any other jurisdiction, including the Federal.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

eDairy News Spanish

eDairy News PORTUGUESE