Prince William believes Sam Elsom is onto something that could help heal the planet, but right now, Elsom’s golden elixir sits in a tank in a Tasmanian field, unsold and on a countdown to becoming useless.

He’s got 10 months. Ten months to shift $1.5 million worth of a seaweed supplement he has devoted the past five years of his life to producing or it will outlive its shelf life.

Yet Elsom remains optimistic his plan to put a dent in climate change will succeed. Frustrated, but optimistic. He’s got to persevere.

“You’ve got to believe you can do it,” he tells Australian Story.

His aim? To significantly reduce the methane emissions from livestock by feeding it an extract from a special type of seaweed called asparagopsis.

Elsom knows it’s just one potential solution “in a whole buckshot of solutions”, but believes there’s only “a sliver” of time left to turn the climate crisis around.

And there is hope. “We have to take that hope and throw everything at it,” he says.

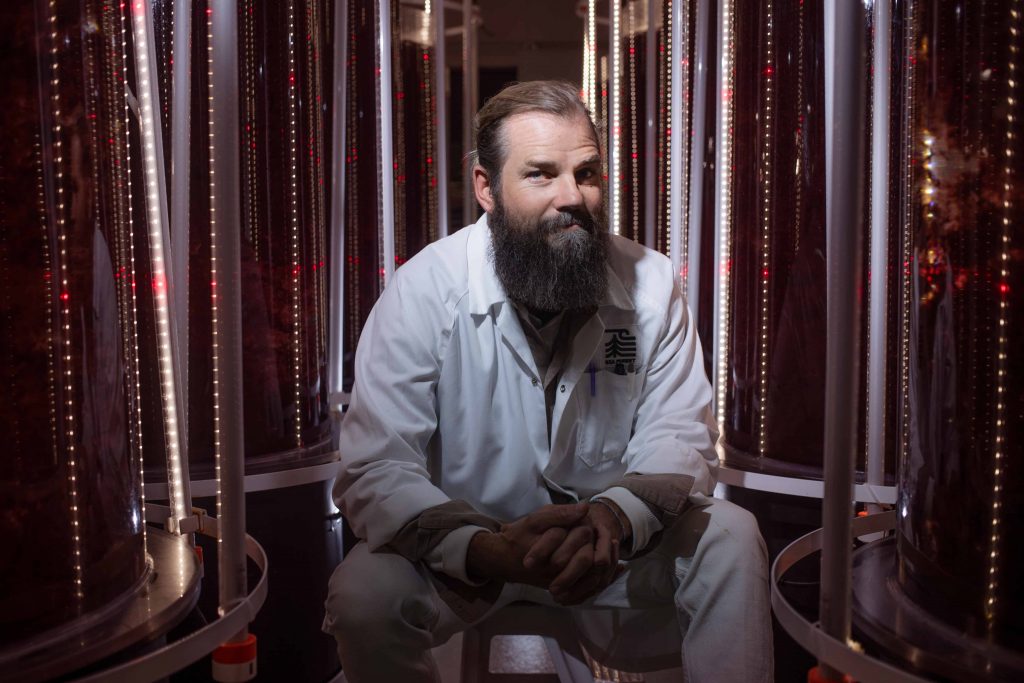

Elsom’s made huge advances since embarking on his ambitious quest. He’s created the country’s first large-scale asparagopsis farm through his company Sea Forest, built a world-class laboratory, made a seaweed-based feed and has the positive results and the drive.

What he doesn’t have is the market to take all his stock.

Bureaucracy, pricing and farmer cautiousness are the stumbling blocks to adoption in Australia, prompting his team to look overseas for buyers.

And now, the rest of the world is looking here after Elsom was named last month as one of 15 finalists in the prestigious Earthshot Prize, the judges of which include Prince William and renowned environmentalist Sir David Attenborough.

Earthshot heralds Sea Forest’s work as revolutionary, saying: “Applying such a solution to 15 per cent of the world’s cattle population could reduce three gigatonnes of emissions globally.”

As a finalist, Sea Forest now has billionaire Michael Bloomberg, a former New York mayor and business media magnate, as one of its global advisers for a year.

And come November 7, Elsom will learn if he’s one of five winners, receiving more than $1.9 million aimed at turbocharging innovative climate change solutions.

He’ll walk down a green carpet at a star-studded affair in Singapore, where guests are encouraged to wear sustainable or recycled fashion.

That will suit Elsom just fine — in a past life, he had his own sustainable fashion label.

Fashion designer-turned-seaweed farmer

On a windswept peninsula on Tasmania’s east coast, Elsom regularly plays host to farmers keen to learn more about the seaweed solution that started taking form in the tiny town of Triabunna in 2019.

Elsom explains how the business now employs dozens of locals, how the asparagopsis seaweed is grown, and how his scientists have developed the seaweed extract that, in current farm trials, is reducing methane output by up to 40 per cent.

Sometimes, as he talks in passionate detail about seaweed and photosynthesis and ruminant methane, they’ll ask if he is a scientist.

“It’s pretty funny when I share with farmers that I have a background in fashion,” Elsom says. “I’ve made a huge career pivot and it does surprise a lot of people.”

His life, he says, has always been a bit unpredictable.

Fashion wasn’t in the mix when Elsom left school. Chemistry and biology were his pet subjects and he’d been accepted into biomedical science at the University of Queensland.

But he decided to take a gap year and head to London. For a “surfie” boy from Noosa, London was a dizzying world of possibilities, captivating him with its range of creative career options.

He’d always loved drawing and had his own fashion style. His mother, Vicki Wood, recalls that when other kids were wearing boardshorts and T-shirts, Elsom would don an op shop waistcoat, topped off with a bandana or maybe a jaunty pair of John Lennon-style glasses.

So, he enrolled in a fine arts course, which led to fashion design, and he was hooked. On his return to Australia in 2000, he worked for other designers before creating his own label.

It was going to be different. “Ethical practices” and “sustainable products” were the hallmarks of his brand at a time when such buzzwords were just entering the lexicon. “We were trying to create elevated fashion with sustainability at its core,” says Elsom, whose beach upbringing instilled a deep connection with nature.

His garments were stocked in leading department stores in London and New York, and Elsom found himself travelling the world to meet with suppliers and ensure workers’ conditions were good.

But the idea was before its time, with consumers unprepared to pay the extra cost. Elsom struggled to shift his garments. He scaled back and started to look for “something with more purpose and meaning and a way to have a bigger impact on the environment”.

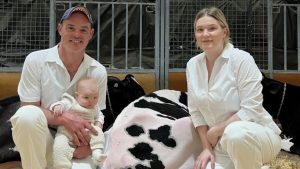

It arrived in 2017, when he and his designer partner Sheree Commerford watched a Climate Council webinar about the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

Commerford recalls: “We were both shocked and horrified. It scared us. We could see data on how fast global warming was occurring and how real that was for the first time.”

At the end of the presentation, some solutions were offered. One involved seaweed.

“Sam turned to me, and he said, ‘That’s it, I’m gonna grow seaweed,'” she says. ”And I was like, ‘OK. Really?'”

Elsom says: “I felt like it was almost a call to action that we need people with entrepreneurial nous to roll up their sleeves and help drive this for the planet.”

He plunged deep into research and discovered a groundbreaking 2016 paper from James Cook University and CSIRO that showed asparagopsis seaweed has a suite of compounds that switches off the bacteria that produces methane in the digestive systems of cows and sheep.

“I was really excited,” Elsom says. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is so easy.'”

It wasn’t. He’d need all his entrepreneurial nous to take a research paper and bring it to life as an innovative, methane-busting business.

‘We gave it a crack’: Taking research commercial scale

It’s good for a giggle, the idea of burping cows. “I remember when it was a bit of a joke,” Elsom says. But it’s deadly serious for the planet.

There are, says biologist Lesley Hughes, a member of the Climate Council, about 1.5 billion cows in the world, and about 1.1 billion sheep. “That’s an enormous amount of methane going into the atmosphere,” Hughes says.

“Methane has always played second fiddle to carbon dioxide in discussions about global warming. But that fiddle is getting noisier because the concentration of methane in the atmosphere is accelerating faster than the concentration of CO2.”

Elsom can rattle off the statistics; methane has about 28 times the warming impact of carbon dioxide, and agriculture accounts for about 15 per cent of global emissions.

But when he first picked up the phone to talk with Rocky De Nys, one of the authors of that groundbreaking paper, he was just a man with a dream. “I remember being nervous about having the right language and understanding some of the science,” Elsom says.

De Nys was intrigued by this environmentally conscious fashion designer and set aside time every Friday afternoon to talk about seaweed and methane.

Elsom grasped the scientific work quickly. “He’s obviously a very clever individual,” says De Nys, who has a “really simplified” way of translating the effect of reducing the burps of livestock. “Think of a cow as a car and that the methane emissions from a cow equal a car on the road,” De Nys says.

“[If] you take one cow and reduce its emissions completely, you’ve taken the emissions from a car off the road.”

De Nys, who has since started working for Sea Forest, applauds Elsom’s courage to take research and laboratory work and turn it into a business.

But if Elsom was going to grow asparagopsis – which would be a first — he needed someone to help drive the business and secure finance.

He talked with his good friend Heidi Middleton, the co-founder of fashion house Sass and Bide, who recalls him “waxing lyrical about this amazing seaweed”. She put him in touch with Stephen Turner, who had been involved in getting her sustainable fashion business off the ground.

Turner figured he’d have a cup of coffee with Elsom, then say farewell and good luck. A week later, after doing his own research, Turner called Elsom. He wanted in.

There’d be little chance of raising capital without proof they could grow the seaweed. They started on land first, a two-year process of trial and error, with Elsom and Turner footing the bills for university research and scientists.

Their brains trust finally cracked it, but the next hurdle was growing seaweed at commercial levels, which meant growing it at sea. Many doubted it could be done. But, Elsom says, “we gave it a crack”.

One day, an underwater drone was deployed to look at the seaweed they had “planted” on ropes submerged in the waters off Tasmania. It was in full bloom.

1.5m doses of seaweed ready to go

With a few calibrated squirts of the oily seaweed supplement into their feed, the dairy cows on Richard Gardner’s Tasmanian farm become far more pleasant to be around.

“There’s absolutely no doubt we’re getting at least 30 or 40 per cent reduction [in methane emissions] and could be getting well more,” says Gardner, a keen observer of climate science.

For about two years, Gardner has been trialling the supplement on 600 cows, about half his stock, through funding from dairy giant Fonterra. It makes no difference to the milk and has not affected the cows’ health.

But Gardner knows Elsom has taken a huge gamble. “I heard a lovely quote the other day: ‘It’s the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world who do.’ And I think Sam’s one of those people.”

Elsom has had big wins. With proof of concept, Elsom and Turner secured $5 million from private sources and $10 million worth of state and federal government grants. And this year, beef from cattle fed the supplement has been used in a burger produced by a leading Australian-owned chain.

Plus, Elsom has proved he can produce at scale — 1.5 million doses of the seaweed supplement are sitting in his tank.

But there’s one big problem: It’s hard to sell. “I never dreamed in a million years that we’d have a situation where we’d have more stock on hand than there were farmers willing to feed their animals,” Elsom says. “But this is the situation that we find ourselves in.”

The roadblock, as it was in his fashion days, is money. It costs about a dollar a head per day to add the supplement to feed, and while Elsom says that would have a small impact on a retail litre of milk, it’s “a cost that has a significant impact on the primary producer”.

Says Gardner: “At the moment, the economics of this don’t work for a farmer.”

‘Tiny cost, huge environmental outcomes’

So, the fashion designer-turned seaweed farmer is now a politician wrangler. He spends a large part of his time lobbying for carbon credits for the feed additive, which would help absorb the cost for farmers. Elsom believes such government assistance could help Australia meet its global methane pledge to reduce emissions by at least 30 per cent by 2030.

Another battle is to change a bureaucratic loophole that denies early adopters of the supplement access to any future carbon credits, which means farmers are more likely to wait for carbon credits rather than take the lead and use it now.

As Brian Mitchell, a Tasmanian federal MP, put to Elsom at a recent parliamentary agricultural standing committee: “What you seem to be saying is the science is established, this stuff works, but you’re currently sort of stuck in this bureaucratic limbo.”

Or, in Elsom’s words: “This solution we’re building requires little to no behavioural change for farmers. So, it’s business as usual and a tiny cost has this huge environmental outcome.”

Elsom is encouraged by the fact politicians are engaged. But he can’t wait for the wheels of bureaucracy to turn. He’s got 10 months.

Europe and the UK are much further down the road to reducing methane emissions than Australia, Elsom says, and interest there is strong. Trials have started on farms in the UK through a supermarket chain, and other European dairy companies are interested, as well as some in Japan.

And now, the Earthshot recognition is propelling Elsom and his vision before a worldwide audience. Just in time. “The next year or two is really critical,” Elsom says. “We’ve really got to find a way to make this work because there’s so much at stake.”

For now, Elsom’s desire to spend more time with his young family in northern NSW is on hold as he crisscrosses the country, meeting with politicians and overseeing the site in Tasmania.

But, he says, they’re aware this big venture, this big risk, is for their future and that of the planet, and they’re right behind him. “What we’re doing is incredibly risky,” he says. “But … the risks are even greater if we don’t.”