Dairy farmers are indignant about beverages calling themselves milks when they are actually made of oats or almonds or sunflower seeds. Even worse, these impostors have been draining away at the market share of what cows produce.

But if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. While farmers loudly voice their complaints about alt-dairy products, conventional processors are starting to churn them out alongside traditional milk, aiming to cash in on their fast-growing popularity in the U.S. One of the country’s oldest dairies, HP Hood, has released a product called Planet Oat. The giant dairy-cooperative Organic Valley is the distributor for a line of almond-based drinks made by New Barn Organics, and a dairy processor handles the packing.

“We wouldn’t exist without Organic Valley,” said Ted Robb, chief executive officer of New Barn, which makes the almond drinks and other nut-based products, including what it calls a buttery spread. “They have a very hard time calling it milk. That really, really bothers them. But they do understand we’re thinking the same way around organic and deeper values.”

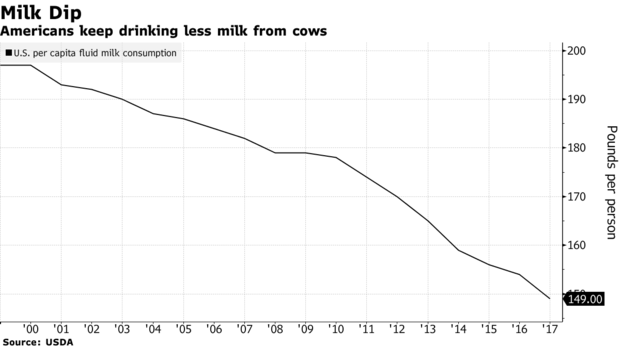

For the dairy industry, though, the value that matters most comes from the cow-based products they sell. That is troubled, to say the least. Americans are drinking 40 percent less milk than in 1975, and prices have suffered a rout. The downturn has been a near-deadly blow to stalwarts like Dean Foods Co., the top U.S. dairy company that has been forced to weigh a sale.

Meanwhile, the plant alternatives are hot. Sales of alt-milks were up 8 percent in the year through Jan. 26, hitting $1.7 billion, according to data from Nielsen. Plant-based cheeses and yogurts, while a smaller category, are seeing even bigger gains. Beyond Meat Inc., the maker of vegan burgers and sausages, surged 163 percent on its May 2 trading debut — the biggest U.S. listing since at least 2008 among initial public offerings that raised at least $200 million.

Outwardly, the dairy industry has harsh words for the plant-based competitors that are eating into their profits.

The National Milk Producers Federation is fired up about the Dairy Pride Act, legislation introduced in the Senate to force the Food and Drug Administration to police labels. In public comments to the FDA last September, yogurt-maker Chobani LLC said using dairy terms on labels for plant-based alternatives was “improper,” “illegal,” and “poses a public health risk.”

At the same time, dairy producers can’t help but get in on the zeitgeist. Chobani recently launched non-dairy products that are coconut-based. Notably, though, the products aren’t labeled as “yogurt.”

The new products aren’t “a replacement to dairy — dairy and yogurt aren’t ever going to be replaced,” the company said in an emailed statement.

Even dairy-icon Dean is in the plant business, and owns almost 70 percent of Good Karma Foods, a maker of flaxseed milk and yogurt.

“Plant-based becomes a cool opportunity to diversify our portfolio so we can be more relevant to consumers,” said Marissa Jarratt, senior vice president of marketing and general manager of the frozen business unit at Dean Foods. Jarratt said she doesn’t see a conflict between plant-based and dairy.

“We want consumers to have options they can choose from,” she said.

Or take the case of Elmhurst Milked in Brooklyn, which made waves a few years ago by transforming from a dairy processor to an alternative maker. It now supplies some Starbucks Corp.’s reserve locations with oat milk. It doesn’t advertise that it has the same ownership as dairy processor Steuben Foods. Steuben also serves as its co-packer and co-manufacturer, blending and bottling their ingredients, said Pete Truby, Elmhurst’s VP of marketing.

For HP Hood, one of America’s oldest dairies at 170 years old, the “horse is out of the barn” when it comes to labeling, said Chris Ross, vice president of marketing. Soy milk launched decades ago and no one challenged the label then, and forcing a change now probably won’t do much to stop the trend.

‘Not Peaked’

“Consumers still have a relationship with dairy, but at same time, their relationship with plant-based like almond isn’t going to end anytime soon,” Ross said. “It’s growing and has not peaked by any stretch of the imagination.”

Michele Simon, executive director at the Plant Based Foods Association, said that while it looks like there’s a fight on the surface, there’s an embracing of milk alternatives by traditional dairy companies because, particularly for processors, it’s “a huge economic opportunity.”

“From a processor perspective, they don’t care what goes into the cartons, they just want the cartons filled,” she said.