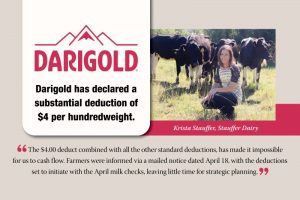

Strong cheese production and slowing exports took a toll on U.S. dairy farmers this year. Class III milk prices fell from $19.43 a hundredweight in January to $13.77 cwt. by July.

On the Class III front, many factors converged to force cheddar cheese blocks down from January’s $2 a pound to the $1.40 a pound range by mid-June, said Corey Geiger, lead dairy economist with CoBank’s Knowledge Exchange division.

Chief among those factors was strong cheddar production as the Midwest brought new processing capacity online, and production rose 4.2% year over year by May, he said in the latest CoBank Quarterly Report.

But milk supplies were ample, and Midwest spot Class III prices ran $6.50 cwt. below the federal order value from January through June — twice as low as the five-year average, he told Capital Press.

Domestic appetite

Domestic cheese consumption has been holding its own, up 1.3% year to date through August versus a year earlier. July consumption jumped 3% year over year for the largest monthly gain of the year, he said.

The butter boom also continued.

“With the fall baking season around the corner, butter markets soared to a new all-time high, moving past $3.50 per pound in October trading on the CME. Spot butter prices have since fallen back to the mid $3.30 per pound range,” he said.

“The sharp upward movement took place even though butter production grew by 4% this year. While butter churns have churned out more butter, demand — which is up 8% so far this year — more than absorbed that extra output,” he said.

Class IV prices held up better than Class III, with a low of $17.95 in April. Class III prices turned positive in August, largely lifted by slowing milk production.

Culling cows

Dairy cattle culling has helped milk prices. In September, the U.S. posted lower milk production totals for a third straight month. The main drivers included unusually hot weather and lower milk output throughout the western states, hindered by fewer cows and lower yields, he said.

While September milk production was reported down 0.2%, USDA adjusted August milk production down to a negative 0.9% year over year and revised July production down to a negative 0.8%, he said.

“Revised numbers suggest that the dairy herd has been shrinking more quickly than previously thought, and that was driven by low milk prices. Intuitively, this makes sense due to the strong dairy cow slaughter numbers,” he said.

USDA revised August dairy cow estimates downward by 11,000 and revised July dairy cow estimated downward by 14,000. Additionally, September’s dairy cow herd represented the lowest figure since January 2022, he said.

Lower exports

To some degree, stronger milk production led to lower milk prices. But lower export volumes played a larger role, he said.

“After posting back-to-back record years on both value and volume, international sales have slowed in 2023. The biggest wildcard for milk prices is China, the world’s leading dairy product importer, which is facing an economic downturn,” he said.

“An improving U.S. and global economy would help boost milk prices as consumers would seek high-quality dairy proteins,” he said.