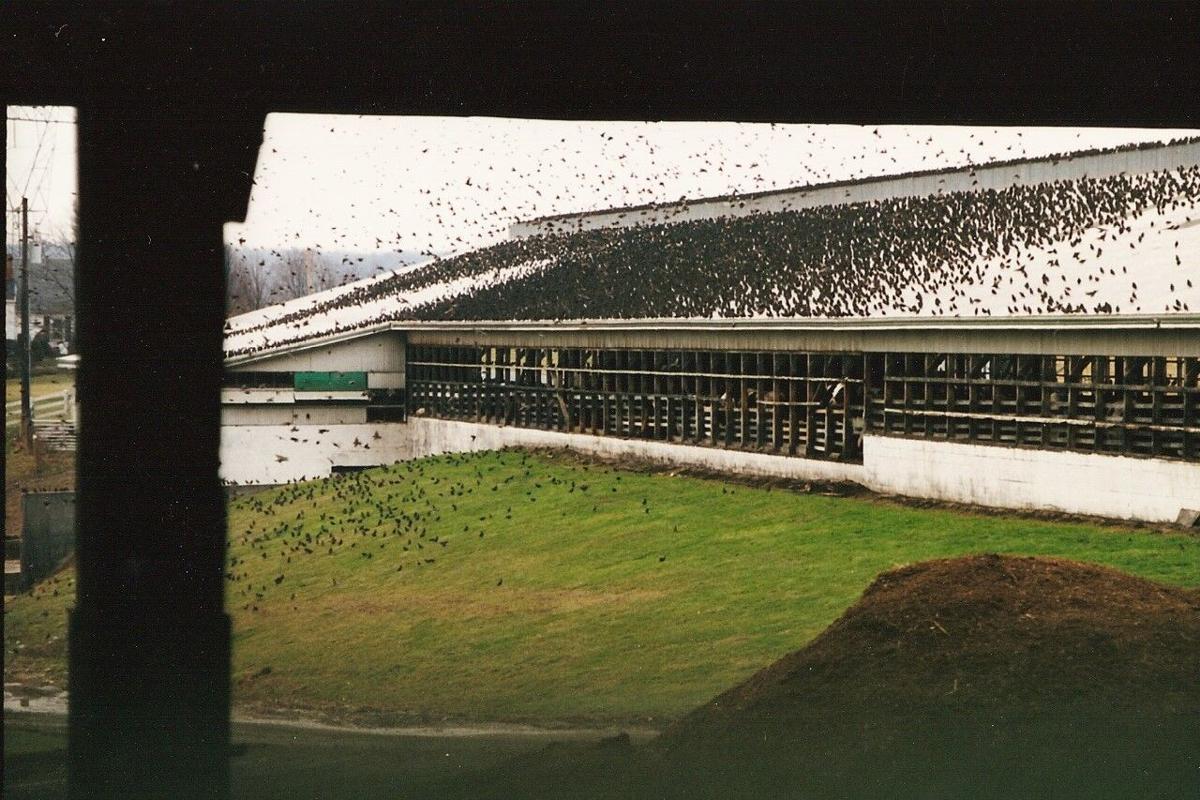

It seems like an insignificant amount if a handful of starlings perch at the feedbunk and feast away. But the diminutive birds can cause enormous losses for farmers, especially when they swarm into a barn by the hundreds or even thousands every time feed is put out for the cows.

And it does happen.

According to USDA’s National Wildlife Research Center, Pennsylvania dairies lose 6.3% of their feed to starlings each year — about 178 million pounds. Large flocks of starlings can drive feed costs up 33% and reduce milk production, and that’s not all.

USDA APHIS photo

While starlings can consume a significant amount of feed, they also generate plenty of waste, triggering a host of disease issues. NWRC research shows the occurrence of Johne’s disease on Pennsylvania dairies can increase as much as 148% where large starling populations are present. Salmonella cases can skyrocket 900%, and veterinary bills can rise 25%.

The losses are staggering if not devastating during a time when feed costs are already climbing.

Nokota Harpster, wildlife biologist with USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service in Harrisburg, said her office has encountered dairy barns with infestations of 10,000-plus starlings that feast every time the cows are fed.

Harpster and the affected farmers have a term for these non-native nuisance birds.

“Rats with wings,” she said. “There’s just tons of them, and farmers experience a huge economic loss.”

Myron Gehman milks more than 300 cows on his farm in Mifflintown, Pennsylvania, and he’s been battling starling problems for years. The birds roost on the large trees around his house, sit on the water fountains inside the barn and feast at the outside feedbunk whenever he puts out TMR (total mixed ration) for his cows.

The numbers vary each year, but Gehman estimates there are hundreds of starlings invading his farm.

“They’re terrible, dirty and defecate all over everything,” he said. “You see droppings where they roost, droppings on the feed, and it’s unbelievable how much feed they can consume. They cluster at the bunk and just peck away at the flake roasted beans in the TMR.”

Gehman knows it’s nearly impossible to eradicate the birds, but when the damage gets to the point where he can’t tolerate it anymore, he calls Harpster to address the situation.

Limited funding prevents USDA Wildlife Services from managing starling populations on every dairy farm where a problem exists, but Harpster said they do respond to those who request assistance.

Calls were higher than normal last year, she said, and the Harrisburg office treated six farms alone. Costs to a farmer requesting treatment from Wildlife Services varies based on mileage, supplies and time, but Gehman said the expense is worthwhile.

“I’ve been very happy with what Nokota does. Starlings are tricky and their behavior changes, so it’s a challenge to control them,” he said. “It’s like trying to figure out rats. They’re evasive.”

USDA APHIS photo

Wildlife Services employs a detailed plan of attack for starling problems. The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Game Commission and state and local police are notified prior to any treatment program. The process starts with pre-baiting for five days using a specialized feed to attract the starlings and get them accustomed to coming to a particular location to eat. Then, USDA biologists come in and put down a treated feed containing a toxicant. Once ingested, the starlings die in three to 48 hours, Harpster said, and there are no secondary effects for other animals, such as a cat or hawk, that may consume a dead starling.

“We require farmers to report all non-target bird species coming in to eat with the starlings,” Harpster said. “But 99% of the time, when you have hundreds or thousands of starlings coming in, you rarely see songbirds.”

Farmers are responsible for cleaning up dead starlings after a treatment, and any that remain are targeted in a second application or harassed with shotgun blasts and chased away.

Gehman said the treatments are effective, but sometimes it requires patience.

“The starlings tend to feed here and roost at a neighbor’s farm. The last bait we did here, by mid-morning the starlings disappeared like they wanted to roost, so we thought it wasn’t working,” he said. “But my neighbor called and said we had a good kill because the dead starlings were all over at his place. They went over there to roost after eating the bait. He didn’t mind cleaning them up because he wanted them gone as well.”

There are an estimated 160 million starlings nationwide, so the problem will likely persist. Federal and Pennsylvania laws do not protect starlings, but the use of avicides in the state is regulated by the Department of Agriculture. Toxicants such as Avitrol and DRC-1339 (which includes Starlicide) are classified as restricted use pesticides in Pennsylvania, and can only be used by a state-certified pest control operator. In the case of concentrated DRC-1339, use is restricted to USDA personnel.