After five years of low milk prices, dozens of farms have gone out of business in recent years. According to the state, Vermont now has 673 dairy farms — a loss of about 100 since 2017.

Those that are hanging on do so with a mix of hard work, off-farm income and sheer dedication to their cows and land. Here’s a look at how three farm families are confronting an uncertain future.

Philip Parent, Enosburg

Philip Parent’s Riverside Farm is on busy Route 105 in Enosburg. His favorite spot on the 320-acre place is a knoll above the barn, where his animals have the best view.

From here, you get a sweeping look at Jay Peak, the Cold Hollow Mountains – and Parent’s own family history in farming. His Quebec grandfather, his pepe, moved to Vermont in 1919 and began milking cows; Pepe’s sons followed the family tradition.

On a recent afternoon of bright sun and peak fall colors, Parent pointed out each place his relatives farmed.

“Where my dad first started is right across there, you can see a silo up there and that’s his original farm up that way. And my pepe, the farm is right there,” Parent said. “My uncle Leo was in the middle, my uncle Theobald was right over this knoll. … So we were all right in a row there, you know, being related to each other.”

Yet Parent, 59, is the last of his line to milk cows. He had hoped his oldest son Thomas would take over, but he moved to South Carolina this summer for a better job and a more secure financial future. Without his son to help, and eventually take over the place, Parent decided to sell off cows.

“That was a hard, stark choice I had to make. You know, I had to do it for my own sake,” Parent said. “And unfortunately that’s playing out too often.”

Parent’s emotions surface when he talks about the struggles he faced. Walking through his barn, his voice catches as he recalls how his father rebuilt it after a barn fire in 1976 so Parent would have a place to farm.

“I’d like to think what I did here had some value,” he said. “I wish we had gotten rewarded financially for it.”

Parent’s not alone. Those five years of low milk prices have left many dairy farmers deep in debt and earning less than what it costs to produce the milk.

“This isn’t right. This isn’t right,” Parent said. “This is where we have to come to a hard reality on that in this country. You know, why is it that the people that feed this country can’t even feed themselves? They have to go to the food banks. They’re on food stamps. Tell me what’s wrong with that picture.”

Travis Tremblay, Enosburg

But Parent’s story does not end with a farm auction and an empty barn. Riverside Farm still ships milk, thanks to Travis Tremblay, a 27-year-old who says he has farming in his blood.

“I hated to stop farming before and I had the opportunity here to get going again,” Tremblay said. “So, you know, we talked about it and he was all for it because he didn’t want to see the farm end.”

So Parent and Tremblay teamed up. The younger man brought his cows to the barn this summer, and they joined what was left of Parent’s herd. Now Tremblay milks about 30 cows.

“It’s all I wanted to do,” Tremblay said. “And I always dreamed of just having, you know, a farm of my own.”

Tremblay said it’s next to impossible for a young person to start farming on their own, without access to land or someone like Parent as a partner — and you also often have to work full time off the farm to get a bank to consider lending you money.

To make it work, Tremblay keeps a grueling schedule. He works as second-shift supervisor at a nearby cheese plant. That job starts mid-afternoon, so he gets to Parent’s barn late morning, milks the cows and has time for a quick shower in the milk house before heading off for eight hours work. He does his second milking after his factory shift, late at night, before heading off to sleep.

“When it comes down to it in your life, you got to do what you want to do,” he said. “And if I’m not going to be doing this, and I’m just going to be sitting at my plain old job and not have a farm at home, I’m going to think the whole time, you know, ‘I wish I was farming, I wish I was farming.’ So I’d rather live it, even if it means doing it the hard way, I’m still living it.”

And asked why he does it, Tremblay talked about the next generation.

“I guess the most satisfying part [is] I’ve got a little girl, and she’s almost four years old. And when she comes and helps out, that’s like the greatest thing in the world,” he said. “And I loved it before her, but having her there brings a whole new meaning.”

Morgan and Jennifer Churchill, Cabot

An hour or so south in Cabot, Morgan and Jennifer Churchill also see family as an essential part of the farm and its future.

On what was Jennifer’s 37th birthday, there was no sleeping in or breakfast in bed. She was in the large free-stall barn by 4:30 a.m. The first job was to hose down the milking parlor and robotic milker. As Morgan did barn chores, Jennifer milked a few cows that aren’t yet comfortable with the robotic device.

The Churchills raise their herd organically, and they sell their milk to Stonyfield Organic in New Hampshire. Over the last few years, they invested in a new barn and computerized milking machine.

The technology tracks data from each cow – its production, milk quality, breeding cycle, even their parent’s history. It also allows the 120 cows to choose when they want to be milked, freeing the farmers from a rigid early morning and late afternoon milking schedule.

That allows the Churchills more time with their children: Samuel, who’s almost 12, and Nora who’s 8.

“Basketball games, school functions are all 5:30, 6 o’clock at night — you know, when the average farmer is in the barn,” Jennifer said. “So now we can be more flexible.”

The Churchills both grew up in farming families. They recently were named Vermont Dairy Farm of the Year for their innovation and success, which includes milk production and quality.

Their kids are a big part of the operation. Samuel can run the skid steer, and both have helped out with the hemp crop growing in a nearby field. But Jennifer said they try not to put too much on them, so they make time to get off the farm as well.

“If you’re going to have to kids, you want to enjoy that part,” she said. “And we don’t want them to not have those experiences because of farming, because they’re not going to want to farm if they don’t get to enjoy, you know, the rest of it.”

Jennifer described Morgan as the dreamer, the one who proposes building a barn by themselves or borrowing money for a robotic milker; she said she tempers those dreams with hard questions.

The couple started small, with a small herd that included the occasional beef cow they milked anyway. In 2012, after leasing it for a few years, they bought the “Wonder Why” Farm on Churchill Road that had been owned by Morgan’s uncle. After remodeling the barn to accommodate more cows, they eventually decided to invest in a modern free-stall facility and the robotic milker.

They have a clear division of labor. Jennifer is more of the cow person, while Morgan — a self-described gear-head who also knows electronics and construction — handles most of the farm machinery.

“We make it look it look easy, but it’s not easy at all,” Morgan said. “But it’s fun!”

The Churchills said the organic market faces many of the same challenges as the conventional milk market: lower prices, slumping demand and competition from plant-based alternatives, such as beverages made from soy and nut products. Jennifer said organic is no longer the financial savior for Vermont dairy.

“It was five years ago. I don’t know if it will be in the future. … They don’t need more milk right now,” she said, “so it would be hard for somebody to get into it and start new.”

The couple said they’d like their children to take over someday, but it’s ultimately up to them.

“If they choose to farm, I hope that there’s still a future here,” Morgan said. “And I think our main goal now is to get our debt paid down as low as possible so that they’re not coming in with a debt that we had.”

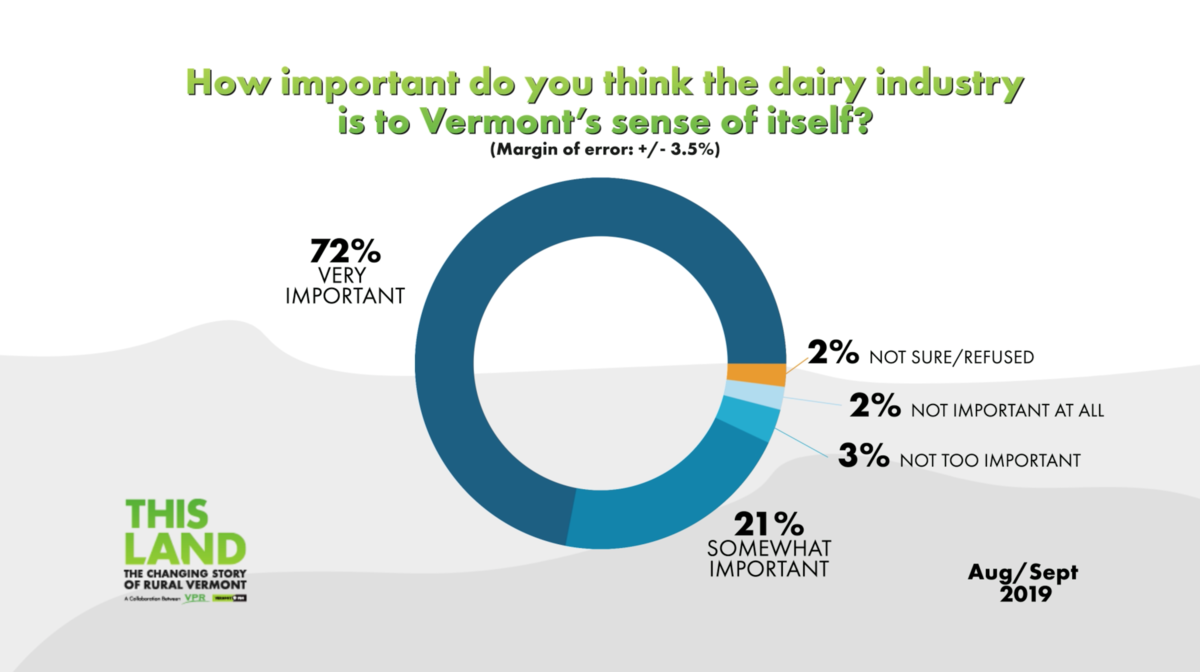

While the VPR-Vermont PBS Rural Life Survey found overwhelming support for dairy farming, Jennifer said she wishes more people would actually learn about farm life.

“And realize where their food comes from,” she said. “It’s important. … I think you have the two sides of Vermont: you know, you have people are way into the land and want everything on natural and organic. And then you have the other side that has no idea where anything comes from. And we need to get that happy middle ground again. Because there’s not many of us left.”