Type “Wisconsin dairy farms” into a search bar and the headlines won’t inspire images of happy cows grazing bucolic green fields under skies filled with peaceful, billowy clouds. In fact, it might make you think that the Wisconsin license plate’s take on that image is beginning to feel awfully outdated. It begs the question: Can we still call ourselves America’s Dairyland if we lost more than 40,000 dairy farms in the last 40 years? Paoli, a tiny community southwest of Madison, may illuminate a new way forward for small farming towns everywhere.

Something remarkable is happening in the unincorporated community of Paoli. As you kayak the Sugar River south through acres of alfalfa and corn, you come to an oak savanna grove. Nearby, you’ll find a grassy lawn brimming with people on folding chairs and picnic blankets, which lie next to an old stone mill, then disappear as you float underneath Paoli Road. Cars pack either side of the road, crowding a smattering of one- to two-story buildings — some in various states of disrepair, others freshly painted, perky and welcoming. Out of your kayak and onto a stretch of no more than 500 feet, you walk past the local pub into Landmark Creamery, where you can buy sheep’s and cow’s milk cheeses from one of the most impressive cheesemakers in the country. Just four buildings down, seated for brunch at the old schoolhouse, you’re about to take a bite of your omelet when you bump elbows with the person at the table next to you. Turns out it’s the farmer who produced the eggs on your plate. You finish the day across the street at a bygone factory, brown brick and sprawling gray, with a patio and walking trails out back where you might gaze at the Sugar River, thickets of greenery and cornfields. As you lick around the sides of a cone of soft serve, you catch a glimpse of a white dairy barn in the distance. There, 65 Holstein cows are being milked for the next batch of fresh ice cream at Seven Acre Dairy Co.

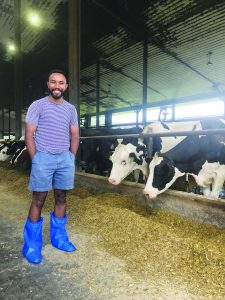

Paoli isn’t another slowly withering Wisconsin farm town. The people of Paoli — population 153 — are involved in a rare approach to community building that rests on the foundation of hyperlocal food systems. They’re looking to historic ways of life as a path forward for both farming and doing business — an approach that could become a model for growing small towns without sacrificing an ounce of local flavor. Tom Sarbacker, whose farm lies in the distance with those aforementioned cows, credits Landmark Creamery’s co-founder, Anna Thomas Bates, with perfectly summarizing what’s happening here: “She said the catchphrase of the people will be, ‘You traveled farther to come to Paoli today than the milk did,’ ” Sarbacker says.

This is a revival story. The last chapter of Paoli’s dairy history ends and begins around the same time family dairy farms began to consolidate into the megalithic operations we’re more likely to know them as today — right around when the Paoli Cooperative Dairy Plant shuttered. For nearly 100 years — from 1888 until the plant’s closing in 1980 — farmers in Green, Dane, Iowa, Rock and Lafayette counties brought their milk to the cooperative, where it was churned into sweet cream butter and Swiss cheese, among other dairy products that were still cutting-edge at the time. What started as a group of just seven farmers would become a leader in refrigeration and fluid milk technology on the forefront of bulk wholesale and retail packaging of consumer dairy goods. And with the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s world-class dairy research facilities just 15 miles away in Madison, the little dairying engine in Paoli was set for success.

Then it all seemed to end. A 1980 Capital Times article reported a “milk war,” set off by the Pabst family (of Pabst Brewing Co.), who built a dairy plant at Pabst Farms in Oconomowoc in 1908 and acquired the Paoli plant in 1955. “The [Pabst] family had failed to keep the plants abreast of the times, did not diversify into other products, and could not survive in today’s competitive milk market,” Nick Pabst told the Capital Times newspaper at the time.

That marked the end of the golden age of dairy farming in Paoli, or at least of the farmstead economy. At peak, some 250 family farmers around southern Wisconsin raised their herds of a few dozen head each to milk for the Paoli Cooperative Dairy Plant — and the community of Paoli grew around it. In the factory, men processed milk, churned butter and made cheese that women packaged and prepared for market. “Our milk used to go there years ago,” says Sarbacker, a fifth-generation dairy farmer in Paoli. “A couple of my brothers and sisters worked at the milk plant. I mowed the lawn over there. Then, in 1980 when it closed, our milk went somewhere else.”

In the late 1970s, as farms were already being told to “get big or get out” — the infamous mantra preached just a few years earlier by President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz — consolidation paved the way for industrialized operations, commodity monocrops and the eventual demise of 40,000 Wisconsin dairy herds. The dairy plant in Paoli, which had always collected milk from human-scale dairies, couldn’t keep up with this accelerated flow of industrial production.

Despite the factory’s closure, Sarbacker and his wife, Vicki, kept the family farm going, determined to stay small in the face of mounting challenges. Up the road, another fourth-generation Paoli dairy farm run by Junior Eichelkraut (his son, Darren, is now the fifth generation) would do the same. Thanks to hard work, grit and perhaps a little luck, they’re both still here, with herd sizes between 50 and 70 cows. Compare that to the largest dairy farms in the state, which milk close to 10,000 cows. “We went certified organic in 2010 as a means for me to continue the farm because we didn’t want to get big,” says Darren Eichelkraut, whose farm, Breezy View Dairy, sells exclusively to Westby Cooperative Creamery. Sarbacker’s Fischerdale Holsteins operates what would be considered a “conventional” dairy as a supplier for Foremost Farms.

Many dairy industry leaders would have called either of their modest approaches ill-advised. And neither farmer would have guessed that staying small would one day pay off so serendipitously. But that’s exactly what it felt like when an $11 million restoration of the Paoli Cooperative Dairy Plant reopened the factory earlier this year, creating a new customer right down the road.

By 2019, Paoli had already earned a reputation as a destination for shoppers. Artisan Gallery, which later became Abel Contemporary Gallery, occupied the Paoli Cooperative Dairy Plant for just over 30 years and made Paoli a haven for artists and art buyers, marking Paoli’s first reinvention. Then, in 2019, the gallery packed up and moved to Stoughton, once again leaving the plant derelict. It lived in transition as apartment housing, among other things, until Nic Mink took a fateful kayak ride down the Sugar River. Mink, a food systems academic turned entrepreneur, purchased the plant in 2021 and began to uncover its history. “What I’ve thought a lot about is, like, ‘Wow, there’s this small-dairy farm thing that’s kind of missing from our local food story, surprisingly,’ ” Mink says. “And why is that? And what can we do to change that?”

A two-year renovation turned the old factory into Seven Acre Dairy Co., keeping much of the original character and structure of the building intact. The space is now a cafe, restaurant and boutique hotel that tells the story of a significant era in Wisconsin dairy farming history. Mink brought in a team of talented Madison chefs, including Kyle Kiepert and Ben Hunter, to build a food program for The Kitchen and the Dairy Cafe and breathe life into recipes passed down by outstanding early 20th century farmstead cooks. Mink partnered with Landmark Creamery cheesemakers Anna Thomas Bates and Anna Landmark to outfit a state-of-the-art microdairy operation in the building, effectively bringing the factory full circle. But they won’t be making cheese. “It would have been very, very expensive to set up a modern cheese plant in that old situation,” says Thomas Bates. Instead, they’re processing Sarbacker’s milk into soft serve ice cream and using traditional methods to churn local whey cream into small-batch butter. “We built a business model, more than anything, to allow people to come here and be stewards of this really remarkable Wisconsin landmark,” says Mink.

Most ambitious, though, is Mink’s commitment to truly hyperlocal sourcing. “There’s nothing stopping us here from 85% of our food coming from within a mile of this spot,” he says. That commitment includes sourcing milk from Sarbacker’s farm and veal and retired dairy beef from both Sarbacker’s and Eichelkraut’s farms. Eichelkraut’s neighbors, Mike and Dagny Knight, own an aquaponics farm that’s partnered with Seven Acre to supply the kitchen with greens, an array of vegetables, edible flowers, microgreens, tilapia and bluegill. “[It’s] very unique to have a facility that can grow 365 days a year and grow pretty much whatever you need,” says Andy Ziegler, managing director at Seven Acre Dairy Co. Chefs from Seven Acre can pop over during kitchen prep and harvest anything that inspires them for dinner service.

A small dairy farm having a local client, and that client’s facility having a view of that farm, are unusual occurrences in the dairy industry these days. “This is something cool that actually happened to a small farm,” says Tom Sarbacker. Once thought highly unlikely or even impossible in today’s dairy industry, having the opportunity for a more localized market inspires hope. “If we can make a little bit more selling our stuff locally like this, it will help us be able to sustain and help us keep going,” Sarbacker says — and his son, Joe, who is also his partner at Fischerdale Holsteins, says the potential is even greater. “I feel like we’re excited about [the possibility of] that demand growing even past them,” Joe Sarbacker says.

You’ll be lucky to find a place to park your car — you’ll see many vehicles with Wisconsin plates, but also out-of-state tags — on a pleasant summer day anywhere off downtown Paoli’s single main drag. “In the early ’80s, most of Paoli was abandoned after the mill shuttered,” says Julie Walser, owner of The Paoli Road Mercantile and president of the Paoli Merchants Association. But a surge of interest from nearby Madison, Verona, Mount Horeb, and even Milwaukee and Chicago has slowly built over the last decade or so around Paoli’s arts, music and recreation scene. There’s live music in the park at The Mill, fish fries at Paoli Pub & Grill, craft beer at Hop Garden and upscale farm-to-table fare at Paoli Schoolhouse American Bistro. Visitors will find arts and novelty at the Paoli Road Mercantile and Lily’s Mercantile and Makery, and they can kayak on the Sugar River and bike the trails leading in from nearby suburbs.

“You can come in and you hit the paydirt as far as food, entertainment, nice people, watch a dog catch a Frisbee,” says Lori McGowan, owner of The Mill Paoli. Several hundred people make the trip each weekend — Seven Acre Dairy Co. has the capacity to double, or even triple, that attraction. “And it’s happening in such a small place,” adds McGowan.

But what if the hype surpasses its size?

Paoli’s boom has raised questions about what’s to come for the unincorporated community. Can Paoli continue to develop on the scale of $11 million investments and still hold onto its rural, small-town character — and can its infrastructure support it? Parking, overcrowding, competition, outsiders — these are all concerns about Seven Acre Dairy Co.’s success. And these tensions were mounting in Paoli long before Seven Acre arrived. “We’ve been really busy the last couple of summers, to the point of, like, there’s nowhere to park; it’s hard to get across the street; there are no public bathrooms,” says Debbie Schwartz, owner of the Paoli Schoolhouse American Bistro.

Parking, especially, seems to be an issue. The community has only one main road — Paoli Road is often so densely packed with cars that it’s hard for traffic to move through — and virtually no space to develop more parking. (It’s worth noting that Seven Acre Dairy Co.’s development did add significant parking to the community.) Town of Montrose chair Roger Hodel says that the township is not looking to purchase land for parking at this time, although it did add 15-20 lanes around Paoli Park and designated parking in a cul-de-sac where Paoli Road used to connect with Highway 69.

Despite some gripes about increased tourism and competition, many Paoli business owners agree that Seven Acre Dairy Co. is good for local commerce, and therefore the community. In general, more people coming to town to visit Seven Acre means more business for everyone else. Carly Eppings, livestock manager at Green Fire Farm, one of Seven Acre’s pasture-raised meat suppliers, is open-minded about the diversity that tourism can bring to Paoli. “I don’t think it’s threatening to create a welcoming space to enjoy good food and to enjoy people’s company,” she says. Mike Knight, who co-owns the aquaponics operation on Sun Valley Parkway, adds, “If you walk into the pub [on a Friday or Saturday night], there’s probably a different group of people that are over at Seven Acre or in the Schoolhouse, and I hope that’s good.”

It’s unlikely that Paoli can expect another development the size of Seven Acre Dairy Co. The community is, for the most part, hemmed in by the highway, as well as county and state land. It’s also bordered by acres of farmland that the Town of Montrose (where Paoli is located) has a vested interest in preserving. Mink suggests it might be in Paoli’s best interest to build with an eye toward keeping nearby small dairy farms in business. “It might seem paradoxical, but I feel like Paoli needs to strongly develop around this agricultural and local food purpose,” Mink says. “I think in many ways to not get eaten up by the maw of Verona’s and Oregon’s and Fitchburg’s — and to some extent, soon Belleville’s — development.”

All across the state, displaced dairy acreage is being snapped up by developers. If any of the dairy farms in Paoli were to sell, that land would be at high risk of becoming commercialized or developed. “Farming is cash poor and land rich, but the hope is that no one ever cashes in on that land … [so] that we just keep passing it [on],” says Sarah Sarbacker, Joe Sarbacker’s wife and partner at the farm. But the challenges of the dairy market make that hope less and less of a viable option for small dairy farms.

“It’s a market-based system, but it’s not anywhere close to consistent,” says Joe Sarbacker, of the dairy market. Fluctuating milk prices mean farmers don’t know what they’re going to be paid year to year. “To have someone else continuously tell you what you get paid makes it scary,” Eichelkraut says. Small conventional dairies are likely producing a more artisan product, but they lose out on premium prices because they lack volume. Tom Sarbacker points out that haulers don’t have to make as many stops when a large dairy can fill the whole truck, earning those dairies a better price per pound because they can produce at a greater scale.

Seven Acre Dairy Co. and Landmark Creamery’s microdairy operation is able to offer an alternative to the traditional dairy market for these small farmers by satisfying regulations around sanitation and health. It allows them the unique opportunity to take milk directly from the Sarbackers and use it to produce butter and soft serve in their own facilities. They can pay the farmers an above-market price and offer them a more consistent salary. Eichelkraut produces a total volume that is too large for local infrastructure to handle, but it helps his bottom line that Seven Acre is putting retired dairy cows and veal from his and Sarbacker’s farms on their menu. “Now [cull calves] are an asset rather than a waste product,” says Eichelkraut, who might get only $10 at auction for a Jersey calf.

Many small dairy farmers want to continue working directly with livestock and pass that management style down to the next generation. One of the contributing factors to consolidation in Wisconsin dairy farms — and farms around the country — is that the next generation is leaving the farm as their parents age out, lured into the city by the promise of higher-paying, more comfortable jobs. Jacob Marty of Green Fire Farm says, “If you want to get new people [into farming], you’re going to have to have a job description that’s a little better than what small-scale farmers currently have.” It might encourage the next generation to take a chance on farming. “As the generation running it now, if you can do it in a comfortable way where you’re enjoying yourself, your kids, or even the neighbor’s kids, will think, ‘They weren’t always upset or broke or having issues,’ ” says Eichelkraut.

Seven Acre Dairy Co.’s effort to adopt historical business practices and commit to neighboring dairy farmers and local sourcing creates a dual solution: Small dairies are supported with consistent, premium prices, which help them stay on their land and manage their workload, and Paoli holds onto its small, rural scope. “If you bring enough consumers here and make this thing all about local food and local dairy, you build the political will and you build the economic rationale for keeping a little bit more of this in farmland and food production,” says Mink.

And even the act of intentionally preserving the buildings that already stand in Paoli — such as the historic mill and the schoolhouse — has radical implications. “Hopefully, we do well enough that we can save this corner from the McDonald’s in 10 years,” Mink says. “Save this farmland from the 72-house tract.”

There’s still a lot to be done at Seven Acre Dairy Co. if it’s to fully realize its goals. It’s only been open for about seven months, and while business has been flourishing, there’s plenty of room to grow. Mink intends to purchase milk from Sarbacker’s at least once a month over the first year, and hopes to grow that demand to the point where they can take all of their milk in three to five years. He also thinks it’s possible that the Seven Acre kitchen could grow anywhere from 50% to 75% of its produce up the road at Knight’s aquaponics farm. There’s no doubt Seven Acre will need to diversify at least some of its sourcing beyond Paoli — and staff has been realistic about that, bringing in fish from the Red Lake Nation, purchasing pasture-raised meat and eggs from Green Fire Farm in Monticello and sourcing cream from Cedar Grove Cheese in Plain, though they’re looking to source cream closer. Mink is transparent about the loftiness of Seven Acre’s goals: “I don’t know if we’re going to get it right, but I know that we’re very thoughtful about this.”

For now, at least, Seven Acre seems to have successfully restored the Paoli Cooperative Dairy Plant to its former glory, not just as a dairy production facility, but also as a gathering place for the community. “It really was the hub where so many people sent their milk,” says Joe Sarbacker. “Now it’s revitalized that — everyone is coming to see that and feel that and connect with that.” Tom and Vicki Sarbacker say that they run into someone they know almost every time they stop in — which is often — and it’s reconnected them to many friends they had lost touch with. Seven Acre has been the news at all the recent weddings and gatherings in their circle. And while for dairy farmers, it’s personal, the restaurant, the cafe and the boutique hotel bring in a diverse crowd across socioeconomic backgrounds. Mink says, “We wanted to build a concept that brought a lot of different people together.”

It’s not easy to name another spot in Wisconsin — and maybe even in the country — where this sort of business model for small dairy sourcing, historical restoration and community collaboration is taking place. “We’re able to do this because [we have] a profound amount of financial and intellectual resources that have all been thrust into this experiment,” says Mink. Most small communities don’t have $11 million at their disposal. But if there was more intentional investment from local entrepreneurs, and certainly more dollars from the state to rebuild markets in favor of small dairy farms, could the approach in Paoli be a model for rural communities?

“I feel like there were certain indicators in this specific region that allowed us to develop and continue to develop this in a very unique way,” says Seven Acre managing director Ziegler, who is dubious that other towns could replicate what’s happened in Paoli. “[Also], having two heritage farmers here, who have been here since the early 1900s, that are still producing on a small scale, is unique.” Yet he thinks that at least digging into the historic potential of a small town and using that to guide the path of development could be replicable “in any community across rural Wisconsin for sure, and probably across the nation.”

“That’s what’s so cool about Paoli,” says Tom Sarbacker. “The buildings were just falling down, but someone has taken a hold of almost every one in here and made it into something.” And most of those spaces are based on food. In many ways, the Paoli Schoolhouse American Bistro and The Mill Paoli (and Landmark Creamery) paved the way for Seven Acre to take that investment in local food systems one step further. Where rural communities around Wisconsin are so often built around farming, supporting existing food systems remains the most obvious answer to creating self-sufficiency and economic security. “It’s something that the community can take pride in and it also just has so many downstream effects,” says Jacob Marty of Green Fire Farm. Darren Eichelkraut adds, “If they can make this work, I think it would spark it in a lot of other places — a lot of dying communities.”

Maybe it’s not even about the model and the ability to superimpose it onto other communities. What if what matters most, at the end of every day, is that you can say you went out and made a better life for your neighbors? “[I think] that’s enough,” says Mink. “Just a couple of people’s lives have improved because of a relationship — have become more rich, have become more full.” When resources and opportunities are constrained by size and location, people find the will to build relationships that often function outside of traditional ways of doing business. “A work ethic that [stuck with me] ever since I was in Mexico is, ‘I help you out, you help me out’ — and that way we grow together,” says Paoli Schoolhouse American Bistro chef Luis Garcia. “And I feel like that’s what we do here.” Keeping dollars circulating locally, supporting your neighbors, honoring history — those things prevail in Paoli.

Whether Seven Acre Dairy Co. can achieve what it’s set out to accomplish is a story that can only be told over time. But, for now, it’s given local dairy farmers something to believe in. “What this place makes you feel like,” says Tom Sarbacker, “is it’s kind of easier to walk to the barn in the morning.”