With cows producing more effluent than milk, the logistics of dealing with the huge amount of waste have resulted in an entire industry devoted to helping farmers manage effluent. Farah Hancock visits the Effluent Expo and asks industry experts what happens to all the poo.

Talk to old-timers who milked before television was colour and they’ll tell you stories about how cow poo in the milking shed was scraped up with a square-ended shovel and thrown over the fence into a paddock.

There it would compost and later get used in the vegetable garden. Water from washing down the milking shed was directed through a drain into a paddock where it proved to be a bonanza for blackberry bushes.

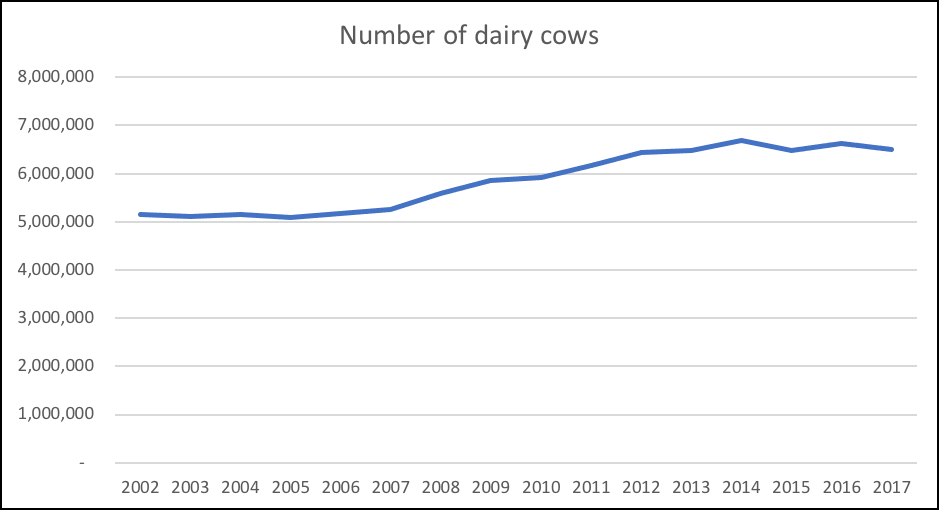

These days with 4.99 million milking cows and each herd averaging 414, flinging the poo over the fence would create towering poo mountains and vast swamps.

Roughly speaking, for every litre of milk that comes out of a dairy cow, around two-to-four litres of effluent also comes out.

While much of the estimated 70 litres of effluent cows produce each day happens in paddocks where it’s left to break down, around seven litres occur during milking.

Add the water used to wash sheds down and the effluent issue becomes, bigger, wetter and more problematic.

Estimations range from as little as 30 litres of water per day per cow, to 70 litres. Taking 50 litres per cow per day of combined effluent and wash-down water produced in the shed as a conservative middle ground, 100 Olympic-sized pools of waste are captured in New Zealand’s milking sheds each milking day.

Over the course of a 270-day milking year, that’s more than 67 billion litres, or almost 27,000 Olympic pools full of poo, pee and water. Putting it in context, the volume of milk processed by dairy companies in 2016-17, was 21 billion litres.

As one of the 100 or so exhibitors at November’s Effluent Expo mildly understated the situation: “Dairy farmers have a lot of effluent to get rid of.”

There’s so much of it, an entire industry has sprung up devoted to its disposal.

“There will certainly be no Christmas presents for the kids this year.”

Driving this industry’s growth is public concern about fresh water quality. Handled poorly, effluent pollutes waterways. Pressure put on regional councils by the likes of Forest & Bird’s report card on effluent compliance means councils and farmers are scrambling to ensure they are getting rid of effluent correctly.

The Effluent Expo was originally set up by Waikato Regional Council and is the only event of its type in the country.

With more than 4200 farms, the council is responsible for monitoring more farms than any other in the country. Its farming services team leader Stuart Stone says there are compliance issues in about 20 percent of farms. Some of the worst examples include overflowing storage facilities and effluent being pumped directly on to paddocks from an open pipe.

Stone: “Many of the balance of farm owners (80 percent) are either already fully compliant, have advised us of plans to upgrade or are investing time and money into farm infrastructure to ensure their operation is compliant.”

The council has now handed the expo over to the industry to run, but remains a sponsor.

A sea of mud-splattered utes in the expo’s Mystery Creek parking lot indicates there’s plenty of demand for the event, which now runs over two days.

Inside the exhibition space there’s a bewildering array of stalls touting equipment options including sumps, stone traps, storage ponds, separators, weeping walls, vibrating screens, pumps, stirrers, travelling irrigators and muck spreaders, as well as an array of digital apps and monitoring systems.

Some vendors have glossy brochures thicker than a Vogue magazine and offer rent-to-own schemes. Effluent solutions can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars depending on their complexity and capacity.

A farming couple from Putāruru, searching the expo for a deal on a pond liner, explained that purchasing even a single item was pricey.

“The cheapest way we can do this is probably spending around $30,000. We’re only a very small farm of 220 cows. There will certainly be no Christmas presents for the kids this year.”

The fines for not buying the liner could be 10 times greater, though. Non-compliance with council rules can incur penalties of up to $300,000 for an individual or $600,000 for a company.

Where does all the effluent go?

Rules around the disposal of dairy effluent are set by regional councils. Surprisingly, there are still some consents around the country allowing effluent to be discharged into waterways. However, many are being phased out.

For most farmers, the option is just to spread it over their paddocks. Done correctly it’s fertiliser for grass. Done incorrectly, where more effluent is spread than the soil can absorb, it can lead to pollution, non-compliance and hefty fines.

The sales patter of Effluent Expo stall holders to passers-by often begins with: “Where are you from? Get much rain there?”

The answer is crucial to managing effluent on the farm.

When it’s too wet, you can’t spread effluent. It either runs off the land into waterways or leaches through the soil, past the roots of grass, and pollutes groundwater.

If puddles of effluent can be seen on the surface of paddocks this indicates soil saturation. Spotted by council compliance officers, effluent puddles are likely to result in council compliance breaches.

“There’s a minefield of information out there on the worldwide web. You do a search for something and come up with millions of results.”

Instead the poo needs to be squirrelled away until the soil dries enough for it to be spread without causing issues. For some farmers this means they need to be able to store 90 days of effluent to get through a wet winter.

Storage options range from huge ponds dug into the ground to above-ground circular pools, similar in appearance to the traditional Para Rubber pool but much bigger.

Left for long periods, there’s the risk solids will settle at the bottom of the pond and a crust will form on the top. To keep the effluent easily spreadable it’s a case of stirred, not shaken. Enormous cake mixer-like devices agitate the pond regularly until the effluent is used.

Once pumped from the pond, there are a number of spreading options.

Tankers that jet out the effluent slurry can be towed behind tractors. A hose can go from the pond to portable irrigation units that the farmer moves around a paddock. Travelling irrigators that slowly winch themselves across a paddock to an anchor point are another option. Centre-pivot irrigation is seen as a gold standard.

Each system has pros and cons.

There’s the initial cost to consider and the labour hours needed. Towing a tanker of effluent around a paddock with a tractor takes more time than using centre-pivot irrigators. Centre-pivot irrigators can have smaller nozzles that may get blocked.

DairyNZ’s environment manager Aslan Wright-Stow says a lot of effort goes into giving farmers the right information.

“There’s a minefield of information out there on the worldwide web. You do a search for something and come up with millions of results.”

The DairyNZ website has a section devoted to effluent systems. It includes guides for various regions in the country, advice for what to consider when designing or managing an effluent system, and information about getting an effluent warrant of fitness.

Wright-Stow says the majority of farmers are compliant with council rules.

“Farmers who are doing the right thing are frustrated by those who are essentially letting the team down.”

Knowing how much effluent can be spread at once isn’t just a case of spreading it until just before puddles form.

Some regional councils have set maximum effluent application depth and rates. Elsewhere, farmers are encouraged to use soil type as a guide, with tables of suggested maximums on DairyNZ’s website. Sandy soils can cope with more effluent than clay, for example.

Farmers also need to calculate how much effluent they are spreading to understand the nutrients that effluent is adding to their paddocks. Effluent contains nitrogen, potassium and phosphate and the levels can vary based on the cows’ diets. Once that’s calculated with the likes of the Overseer tool, the amount of nitrogen fertiliser a farmer applies can be reduced.

Along with soil type, a key factor is future rain, according to Pāmu’s (formerly Landcorp) Taupō environment manager Robert Van Duivenboden. He describes winter-time effluent application as problematic.

“People have a large pond which is filling and weighing on their mind and they’re looking to put it out as often as possible, especially on the shoulders of winter.”

He says it remains to be seen whether “deficit irrigation” can work if the soil is peat or clay.

“Deficit irrigation is where we don’t put 10mm out unless 10mm can be accepted by the soils.

“The regional rules around the country vary, but none of them require deficit irrigation at this time. As a national overview, they really require that you don’t have ponding in your paddocks and you don’t put on an excessive amount, a very large number usually in any one day.”

What happens the day after effluent application is key, Van Duivenboden says.

“If 20mm of rain fall the next day, then you are really going to be flushing that effluent either past the root zones or via overland flow to ditches, drains and streams.

“For a large portion of the winter for many people, effluent must be put out on land in-between the fronts and we don’t really know the fate of that.

“Mostly it stays in our top-soils, but with a full winter to come behind it we don’t know if it moves through the soils too fast or not. Certainly, it never gets to streams. That’s an absolute no-no. But via groundwater? It’s probably unknown for most places in New Zealand.”

A new effluent system on a Pāmu farm cost $400,000.

“That buys you what I see as the industry norm, rather than anything spectacular,” Van Duivenboden says.

“It’s water-efficient and big enough to be compliant. I would love to be able to boast we’ve got something industry-leading here, but many others have got that as well. It does give you a sense of the scale of investment needed.”

Where to for poo?

Water-efficient systems that recycle water are on display at the Effluent Expo. Forsi Innovation’s Derrick Piper says its system is capable of recycling effluent and washing water to drinking standard. A unit used at a Massey University farm produces 1500 litres of clean water per hour. The water is re-used to wash down the milking yard.

“It doesn’t smell. It’s clear. It’s virus- and pathogen-free,” Piper says.

The nitrogen-rich solids that are screened-out with vibrating screens are easier to store because of the reduced volume. They can be spread when the weather is dry.

Despite their high price-tag, systems like this may become commonplace in the future as there’s greater emphasis on reducing water use and ensuring applied effluent doesn’t contribute to nitrogen leaching.

Pressure on farmers to change is coming from councils and public concerns about water quality. But industry is also encouraging good effluent management.

Some smaller milk companies, like Synlait and Miraka, require farmers to have an effluent warrant of fitness. Without a WOF, milk won’t be collected.

The voluntary WOF scheme costs farmers between $800 and $1300, and inspections are recommended three-yearly. Day-long inspections are conducted by independent assessors. Promoted on DairyNZ’s website, the scheme sits outside regional council compliance programmes.

Van Duivenboden says Pāmu farms have effluent WOFs. He describes it as similar to a car WOF.

Asked what he thinks would happen if Fonterra required it, he pauses: “I would say there would be a big rush on compliance.”

Fonterra, the country’s largest milk processing company requires farms be compliant with regional council requirements.

Why doesn’t it require farms to have an effluent WOF? A company spokesperson responds: “We are focused on helping farmers become compliant but how they achieve this outcome is a decision for the farmer, based on what is best for their business.

“For the many farmers who have a long history of managing a compliant system, a mandated WOF would be an unnecessary requirement and cost.”

The Putāruru farming couple shopping for a pond liner think it’s an investment they won’t need to repeat. The 10- to 20-year guarantee on liners should see out their farming career.

“Then it will be someone else’s problem and then there will be another whole set of rules, probably. By then I’m sure dairy farming will be banned in New Zealand. The do-gooders will have their way.

“So long as you like black coffee and dry Weetbix then that’s fine.”