Migrant Justice, a Vermont-based, farmworker-led organization, is pushing for fair wages for the workers that underpin the US dairy industry.

Enrique Balcazar remembers the disillusionment he felt the day he arrived in Vermont from Mexico to work on a dairy farm for the first time.

He was excited to begin a promising new life in America, with opportunities and comforts he could never have imagined back home. But this fantasy was quickly shattered by the harsh reality of dairy farming.

“When I got there, I saw that I was going to be living in an old trailer all by myself,” he says. “No cellphone service. No internet. Just totally alone and isolated. That was my first shock.”

When Balcazar began work a few days later, he didn’t know how to do the job and didn’t understand the language. But he immediately began putting in long hours, seven days a week.

He was excited when pay day came around and he got his first check. “When I opened it, my heart sank. I was only getting paid $3 to $4 an hour,” he says. “For the work I was doing and as hard as I was working, it was much less than I expected.”

Balcazar approached the farm manager, who told him, “it is what it is,” and if he stuck around, he might eventually get a raise.

Months passed, but the raise never came.

Vermont’s dairy industry relies heavily on the labor of undocumented migrant farmworkers. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Balcazar’s story is typical for undocumented migrant farmworkers in Vermont, who now comprise the overwhelming majority of dairy workers in the state.

Dairy farms in the region are under immense pressure to cut costs due to industry consolidation and globalization, which allows powerful agribusinesses to place downward pressure on farmers’ incomes. Farmers then hire migrant workers who they can pay far below minimum wage.

The visa program and federal law designed to protect seasonal migrant workers, such as agricultural workers in California, for example, don’t apply to dairy farmworkers in Vermont because of the year-round nature of dairy production.

As a result, the majority of these workers face dangerous work conditions and live in substandard housing. Despite paying taxes, they do not have the rights of US citizens and are under constant threat of deportation by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol.

Migrant Justice, a Vermont-based farmworker-led organization, was founded in 2010 in response to the death of José Obeth Santiz Cruz, a 20-year-old migrant worker from Chiapas killed in a tragic workplace accident, and the rampant exploitation taking place on most dairy farms.

Its signature program is Milk with Dignity, which enlists powerful corporations to pay a premium to help raise wages and improve conditions on supplier farms. Compliance is monitored by an independent third-party organization.

Will Lambek, an activist with Migrant Justice, says that one of the reasons that dairy workers created this program is because of the state’s failure to address labor and housing violations.

“The structure set up through the Department of Labor and the Department of Health have left farmworkers out and haven’t protected their rights,” he says. “So, that’s why dairy workers created their own model … to ensure dignified treatment for their workers.”

Rubinay Montero, a Migrant Justice leader, marches through Middlebury, Vermont in December 2022. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

When Balcazar was just seven years old, his father moved to Vermont to work on a dairy farm. He would send money back to Mexico to support his family, but the money wasn’t enough, so in 2011, when Enrique was 17, he followed his father to the United States.

As a child of farmworkers, getting a visa wasn’t an option, so he decided to risk his life crossing the border. It was a significant risk, but it was his best chance to earn enough money to continue his education in Mexico.

That’s how he became one of the millions of mostly black and brown migrants and refugees escaping unstable governments and economic crises caused in part by centuries of imperialism, exploitation and deliberate underdevelopment. Many arrive in the U.S. to take jobs that offer low wages and no benefits, that would otherwise remain unfilled and that are essential to the US economy.

After a couple of months working on that Vermont farm without a raise, Balcazar found a new position on the farm where his father worked. It was there that two members of Migrant Justice visited him and invited him to a community assembly. That visit would change everything for Balcazar.

When he showed up at the assembly, he felt a strong sense of community because there was a room full of farmworkers, just like him, talking about the same injustices that he had experienced. It was the first time he realized that his experience wasn’t an isolated incident; the problems his community was facing were systemic.

“For decades, the migrant community has been criminalized and persecuted by a system that wants our labor but doesn’t care about our lives,” says Balcazar.

At that moment, he thought about his parents and everything they had gone through. “It left a mark on me and I had a realization of the challenges and the solution: organizing for our human rights,” he says.

Although Balzcazar was working 60-70 hours a week without a day off, he became increasingly involved in Migrant Justice. At the time, it was starting to organize for freedom of movement, allowing migrant workers access to driver’s licenses. “That was really exciting for me because I saw that people were working together based on those common experiences,” says Balacazar. “And so, right there, I was hooked.”

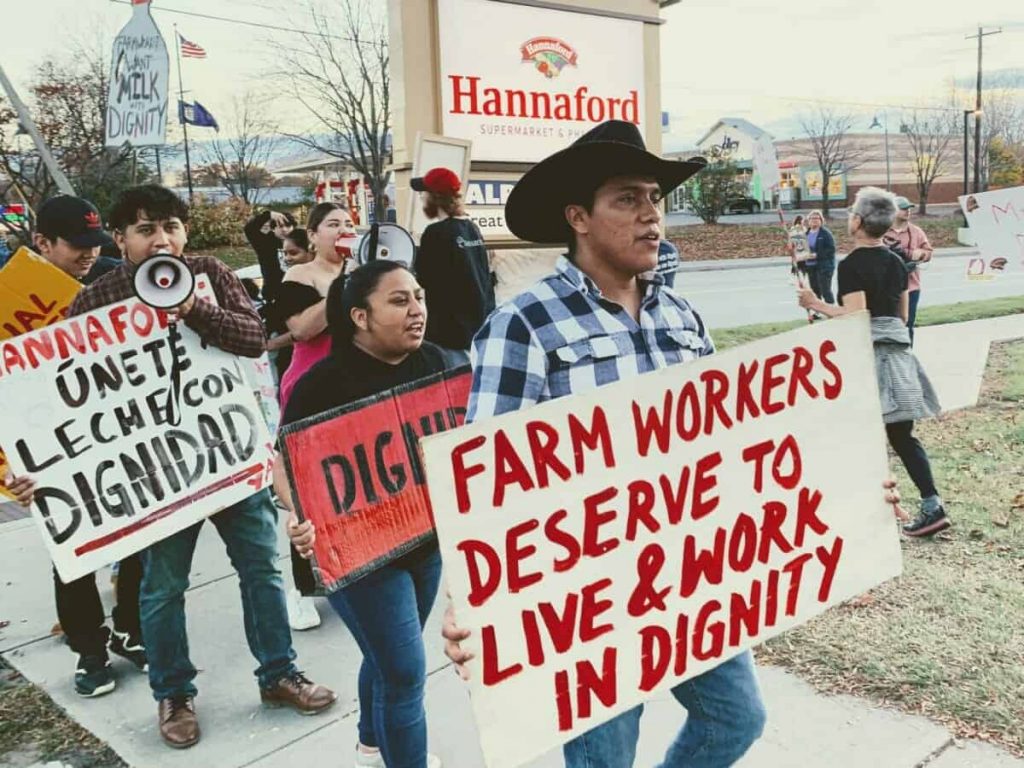

Enrique Balcazar leads a protest at a Hannaford Supermarket in April 2023. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Balcazar has since emerged as one of Migrant Justice’s most visible and vocal leaders. His activism has helped to improve not only his own work and living conditions but those of hundreds of migrant dairy farm workers in Vermont.

After two years of advocacy, Migrant Justice was instrumental in passing a law allowing migrant workers to get driver’s licenses, which has changed farmworkers’ lives in rural Vermont.

Balcazer also became a part of developing the Milk with Dignity program and the campaign to enlist Ben & Jerry’s, which is based in Vermont and is the largest ice cream company in the US with 2022 sales of $910.68 million.

In 2014, Migrant Justice began pressuring the company with protests in front of Ben & Jerry’s stores, picketing its board meetings and marches.

One day, they marched 13 miles to their ice cream factory. “Imagine working 12 hours on a farm, before spending the whole day walking under the sun and going right back to another shift. Those were the sacrifices that we made to defend their dignity,” says Balcazar.

It was during this time that Balcazar and other community leaders were detained by ICE. Eventually, thanks to mobilization from the community, Balcazar was freed.

“That was a really difficult experience, but having gone through it, I want to say this deepened my commitment even more to continue fighting for justice and human rights for my community,” he says.

Migrant Justice eventually won a contract with Ben & Jerry’s in 2017, which covers 100 percent of Ben & Jerry’s northeast dairy supply chain and 20 percent of Vermont’s dairy industry. This has changed the lives of more than 200 farmworkers. Migrant Justice reports that, since the agreement, $3.4 million has been invested in workers’ wages and bonuses and dramatically improving labor and housing conditions. The goal is to expand the program to cover every farm in Vermont and nationwide.

Farmworkers picket in front of the corporate headquarters of Hannaford Supermarket in Scarborough, Maine in February 2023. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Now, Migrant Justice is trying to enlist Hannaford Supermarket to the Milk with Dignity program. Hannaford is headquartered in Maine, with nearly 200 shops all over New England and New York. It’s one of the largest supermarket chains in the Northeast and a significant buyer of dairy products in the Northeast.

“Hannaford has had a number of responses over the course of the campaign and has consistently rejected calls to sit down with dairy workers in their supply chain,” says Lambek.

Hannaford is a subsidiary of the Dutch agribusiness giant Ahold Delhaize, which reported $91.51 billion in sales in 2022. Both companies claim to be committed to respecting human rights.

However, Migrant Justice alleges that labor and housing rights violations are taking place on supplier farms for Hannaford supermarkets. Hannaford has said it has investigated those allegations and that none have been substantiated.

After facing pressure from the public, one of Hannaford’s responses has been to set up its own hotline, called the “Speak Up” line. Workers in its supply chains can submit a complaint if their rights are being violated. When it made the announcement last year, workers decided to take the company up on it.

“Workers on 10 farms submitted complaints, and, through their experience, have shown that this company line is a farce,” says Lambek. “It hasn’t protected any worker’s rights and hasn’t provided any remedy for workers who have been abused.”

Most recently, in June of this year, Hannaford released a statement saying, “Because of the complexity and scope of the issues facing migrant farmworkers, we do not feel this approach is scalable. Nor do we feel that these issues can be solved with a patchwork of loosely affiliated programs like Milk with Dignity working independently.”

Research supports the effectiveness of Milk with Dignity’s approach. Milk with Dignity is an example of a worker-driven social responsibility program (WSR) that is designed and led by farmworkers. It was modeled after the Coalition of Immokalee Workers Fair Food Program and has been shown by a 10year longitudinal study to be “the most effective framework for protecting human rights in corporate supply chains.” Earlier this year, Harvard Law School published a report calling WSR “a new, proven model for defining, claiming, and protecting workers’ human rights.”

Farmworkers pose outside their farm, a participant in the Milk with Dignity Program. Efrain (R) reflects: “Before you just had to do what they told you. No holidays, no sick days, no vacation, no bonuses, no raises. Before we didn’t have protections. Now we do. We feel more dignified.”

Balcazar can attest to how much migrant workers’ lives improve once their employers join WSR programs such as Milk with Dignity. When he reflects on his arrival in Vermont 12 years ago, the change has been drastic.

“Now, you can drive to the store without fear, you can take your family out to a park and, if you’re working on a farm, then, when you’re working, you have dignified conditions that you deserve,” says Balcazar.

Balcazar and his community envision a future where their Milk with Dignity program expands to cover every farm. Public awareness and support can help them achieve this goal.

“The next time that you drink a glass of milk or eat that pint of ice cream,” he says, “remember: the cows don’t milk themselves.”