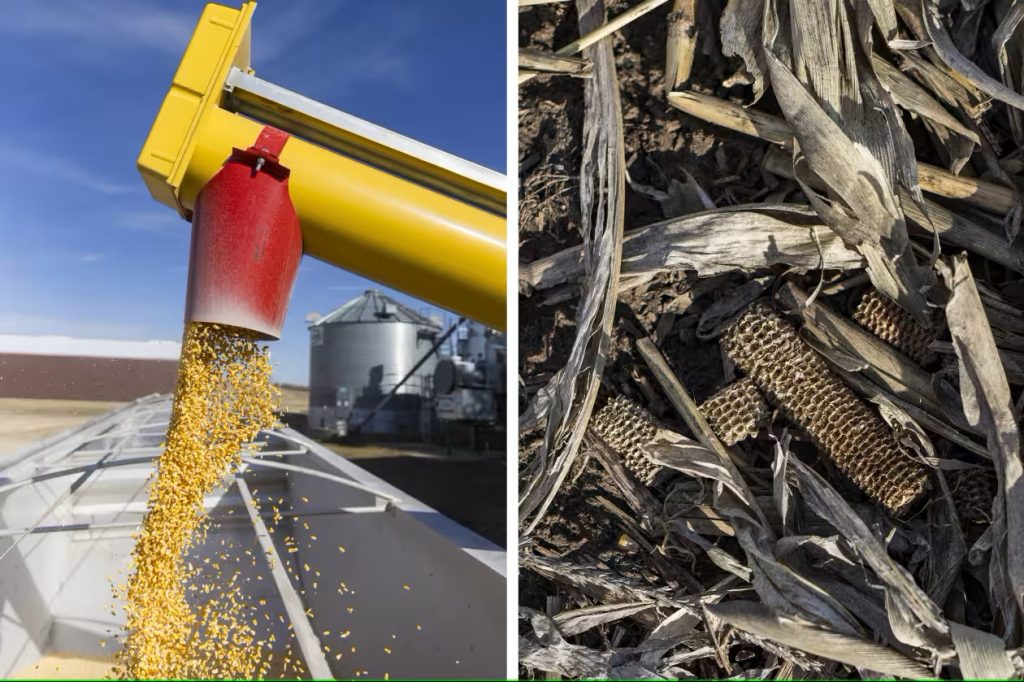

U.S. agriculture exports are at high risk for retaliation when reciprocal tariffs start on April 2.

Rural America sent Donald Trump back to the White House. Now, Trump’s new trade war is putting its loyalty to the test.

At the front lines are farmers like John Airy, who farms more than 1,000 acres of soybeans and corn in Central City, Iowa. Rising costs for everything from labor to fertilizer and a 20% drop in soybean prices challenged his business last year, though he says he managed to break even. This year, tariffs will probably produce new pressure on his bottom line as Trump wages economic warfare against the country’s largest trading partners, which also happen to be the biggest buyers of U.S. farm goods.

“Nobody is expecting to get rich this year. That’s for sure,” Airy says.

The Department of Agriculture expects U.S. farmers to export $170.5 billion for the federal fiscal year, which runs through September. That makes them prime targets for retaliation as countries try to impose pain to dissuade the Trump administration from its trade strategy. The administration’s tariffs and its efforts to shrink the government will also raise farmers’ costs, squeezing them on both ends. If Trump and America’s trading partners lose their game of chicken and get stuck in a protracted trade conflict, farmers could pay the price more than most other industries.

The trade war will enter its next phase on April 2, when Trump says he’ll unveil “reciprocal” tariffs targeting countries that have higher trade barriers than the U.S. The exact targets are unclear, but Trump in March foreshadowed that agricultural products would be in the mix. Farmers should prepare to sell more within the U.S., Trump wrote on Truth Social. “Have fun!”

Farmers may be facing economic challenges, but their optimism about their future prospects in early February was near its highest point since early 2021, according to a survey by Purdue University. Nearly half of farmers said that trade policy was the most important issue for their farm over the next five years, though only 47% thought it likely that a trade war would result in a significant decrease in exports.

Whether trade policy helps or hurts farmers depends on the balance between their gains from protectionism and the costs of a trade war. China, Canada, and Mexico are U.S. farmers’ largest foreign markets, and the three countries have implemented levies on nearly $30 billion in U.S. agricultural exports since Trump’s term began, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation, or about 17% of 2024’s exports.

Some farmers might benefit from increased protectionism, but others probably won’t be able to find enough domestic buyers to fill gaps created by a trade war. In the 2019 fiscal year, the U.S. imported more agricultural products than it exported for the first time in nearly six decades. Much of that swing was caused by Americans’ increased appetite for coffee, cocoa products, and certain distilled spirits that have few domestic producers.

Some products targeted with retaliatory tariffs have almost no domestic markets. For example, China is one of the biggest importers of U.S. pork variety meats, which include hearts, livers, tongues, and other organs that U.S. consumers aren’t likely to warm to soon. In March, China put an additional 10% tariff on such imports, bringing the total levy to 47%.

“I don’t think you’re going to be eating any more pigs feet than you currently do,” says Iowa Farm Bureau Federation economist Christopher Pudenz.

The Trump administration has raised tariffs on Chinese imports by 20 percentage points. In response, China in March put 15% tariffs on its imports of U.S. chicken, wheat, corn, and cotton, and 10% on sorghum, soybeans, fruit, vegetables, dairy, and meat products. Canada’s retaliatory 25% tariffs hit makers of processed foods such as wine, sausages, baked goods, and distilled spirits. Mexico held off on announcing retaliatory measures after Trump said he would suspend until April 2 tariffs on imports that fell under existing trade agreements.

Meanwhile, farmers’ operating costs could also rise because of some of Trump’s other policy changes.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture in February fired 6,000 employees as part of the rapid downsizing of the federal government led by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. Some of the employees who were cut studied infectious diseases and pests that could decimate U.S. crops. In response to some farmers’ concerns, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins this month said the department would bring many of those researchers back. Courts and other quasi-judicial agencies have also reinstated employees from the USDA and other agencies after finding that their terminations were probably illegal.

John Airy at his farm in Central City, Iowa. (Photograph by Kathryn Gamble)

The Department of Agriculture referred a request for comment to a Fox Business interview in which Rollins said farmers are prepared for an “interim period as we move toward what the president has said is the greatest age of prosperity not just for all Americans, but for our farmers and our ranchers.”

Trump “will ensure farmers have the support they need to feed the world, just like in his first term, while simultaneously leveling the playing field and expanding markets for all of America’s agriculture industry,” said White House spokeswoman Anna Kelly.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration is likely to raise farmers’ labor costs. Immigrants without work authorization made up about 42% of crop farmworkers in 2020-22, according to the USDA, with the highest concentration in California’s fruit and vegetable farms.

Costs for farmers’ inputs—such as fertilizer or new farm machinery—could also rise as a result of tariffs. In March, Trump imposed a 10% tariff on Canadian potash, an essential ingredient in fertilizer that has few U.S. sources. Trump also raised tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum, which are used in farm machinery. Prices of hot-rolled coil, a benchmark steel product, have shot up 32% this year.

Rollins has said the administration is considering financial support for farmers. Farm aid could mirror a $28 billion program that the Trump administration implemented during the China trade war beginning in 2018. The USDA made direct payments to producers of “trade damaged” commodities, which included corn, soybeans, hogs, and sorghum. Despite the financial support, farm bankruptcies rose to a record high in 2019, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Many farmers are coming into the new trade war from a position of weakness, after two years of droughts, labor shortages, and rising costs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic, says the Iowa Farm Bureau’s Pudenz.

The trade war could cost U.S. farmers market share. Trade disputes with the U.S. have already led China to seek to rely much less on U.S. soybeans in favor of those grown in Brazil, says John Beghin, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

That happened despite China striking a deal in January 2020 with the Trump administration to buy $200 billion more of U.S. goods and services in 2020 and 2021 than it had bought in 2017, including an extra $32 billion in agricultural products. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said that China didn’t live up to its end of the bargain and that he would press for “catch-up” provisions in any new trade deal.

“Once you have a tariff on U.S. product, the market gets lost very quickly, and even when the tariff goes away, you don’t get it back,” Beghin says.

The DOGE-driven cuts to federal spending may have other ramifications for farmers. The administration is attempting to shutter the U.S. Agency for International Development. In the last fiscal year, USAID bought roughly $2 billion in U.S. commodities including corn, sorghum, and rice for foreign aid. In March, the USDA cut more than $1 billion in funding for programs that gave schools and food banks money to buy food from local farmers. An executive order in February also froze $2 billion in payments for farmers who had signed contracts to undertake conservation programs authorized by President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

Many of the administration’s actions are being challenged in court. But some research projects are probably gone for good. USAID funded the Soybean Innovation Lab at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The lab was trying to help farmers cultivate soybeans in sub-Saharan Africa. The region primarily uses palm oil rather than soy in cooking and food processing. Developing the local soy market would have created new customers for U.S. soybeans, says Peter Goldsmith, the lab’s director.

“There were huge opportunities for the U.S. if [sub-Saharan Africa] flipped to soy from palm,” says Goldsmith.

Goldsmith’s lab also studied soybean red leaf blotch, a fungal disease that hasn’t yet been reported in the U.S. but that could lead to a precipitous drop in crop yields if it ever came here, Goldsmith says.

The lab received its official termination notice from the U.S. government in March, and Goldsmith says all of the lab’s employees will be let go or moved to other projects by mid-April.

Airy, who has worked the land for more than three decades, says he and other farmers are patient. They hope that sacrifices made now will pay dividends if Trump manages to force countries to lower trade barriers or purchase more of their products.

“If, say, you get another 12 months from now and some of these things aren’t being settled and put to bed, we’re going to really start feeling the pressure,” Airy says.

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K