The study from USDA’s Economic Research Service looks at trends in the dairy industry from the 1980s through 2019. It found that the pace of consolidation in dairy “far exceeds” the rate seen in most other agriculture sectors.

“Consolidation in U.S. crop production was widespread across crops and was persistent over time; over 30 years, consolidation in crops doubled. The equivalent measure in dairy shows a 16-fold increase in 30 years,” the report said.

The report found consolidation in hog and egg producers has occurred at a similar pace to dairy, but other livestock sectors have seen consolidation at a much slower pace.

Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that larger operations are able to contain certain costs in ways that smaller operations can’t.

“It doesn’t mean that (smaller farms) are doomed to go away. But over time, they’ve been shifting and changing.”

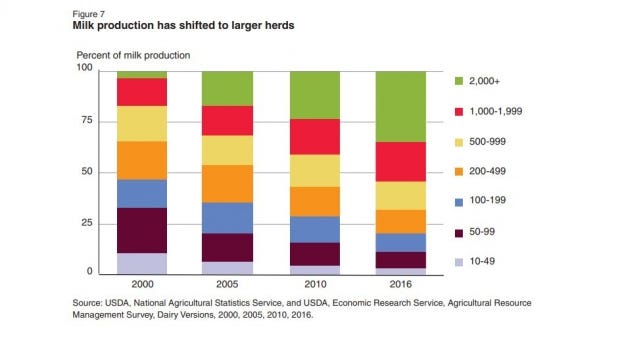

The USDA report found that in the year 2000, farms with 2,000 cows or more only represented 4.5 percent of U.S. milk production. By 2016, that group represented 35.2 percent of all milk production.

The report also shows the number of licensed dairy herds in the country fell by more than half from 2002 to 2019. Herd numbers declined by 4 percent annually through 2017, but that rate accelerated to 6.8 percent in 2018 and 8.8 percent in 2019.

Much of the decline comes from a falling number of small commercial farms, defined by the report as farms with less than 200 cows. The report found that trend has been concentrated in the Midwest and Northeast, particularly in Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Stephenson said the finding isn’t a surprise to many in Wisconsin, where the number of licensed dairy herds has been declining by record numbers in recent years.

“We’ve seen farms that have the types of things going on that indicate that they’re probably last-generation farms,” Stephenson said. “They are smaller. The operators may be older. They may not have a successor that’s coming into there, and their investments to replace some of the capital structure on those farms has just been in a holding pattern. And (leaving the industry) is probably a very sensible thing for them to do as they’re imaging their glide path to retirement.”

But Joleen Hadrich, extension specialist for the University of Minnesota, said the Midwest is losing more small commercial dairies because other regions have already experienced major consolidation.

“The reason why our small dairies have been able to succeed in the upper Midwest and the Northeast is due to the number of processors and local co-ops who are processing the milk. So there’s still a competitive market to where you can potentially sell your milk. And in these other regions, where it’s more consolidated, you may only have one processor as an option,” Hadrich said.

Hadrich works primarily with dairy farms on improving their profitability given the rapidly changing market conditions.

The USDA report shows month-to-month changes in milk prices have grown in recent years. In the 1980s, milk prices ranged from a low of $11.30 per hundredweight — 100 pounds of milk — to a high of $14.30 per hundredweight. By the 2000s, that range has expanded to a low of $11.00 per hundredweight to a high of $21.90.

Hadrich said this price volatility is here to stay, so farmers need to think more about profitability and managing their risk.

“The price of a candy bar consistently increases, right? It doesn’t decrease over time. So it’s a unique challenge that dairy farmers face. So one of the top recommendations I have for my producers is that you really need to know your break-even or your cost of production,” Hadrich said.

She also encourages farms to use forward contracts, where they secure a price for future milk production.

Stephenson said these kinds of risk management tools are how large dairy farms have been able to protect themselves against price swings in the last five years.

“What we’ve tended to see is that our larger farms have been less reluctant to use risk management tools available to them,” Stephenson said. “They’re protecting themselves against the worst of the lows and they’re giving up some of the highs in order to be able to do that.”

Stephenson said there is no existing mechanism to prevent sudden changes in milk price. But he said some dairy processors have been taking their own steps to try to lessen the impact.

“Cooperatives or even dairy plants that buy directly from farms in the COVID crisis simply told their dairy producers, ‘We can’t handle as much milk. You need to cut back 5 percent’ or something like that,” Stephenson said. “They created a big disincentive for milk production above that level. That did reduce milk supply. That did help to rebound milk prices. So those kinds of mechanisms can be used to help moderate price swings.”

Stephenson argues consumers can also have some impact on the future of the dairy industry.

“I do think that a lot of people value a countryside that has an aesthetic to it that may include small farms,” Stephenson said. “If they’re willing to pay for those additional costs that are highlighted by a study like this, then fine, so be it, let’s have more of that kind of industry. But this is showing us that there are costs to maintaining some of the things that we might feel are desirable attributes to a dairy system.”

Tim Trotter, executive director of the Dairy Business Association, said continued consolidation and the growing size of farms is inevitable for the dairy industry, just like many other industries.

“That trend is probably not going to change. But that’s not to say smaller or mid sized farms are not profitable,” Trotter said. “It all comes back to their financial wellness and that’s not always dictated based on the size of the farm.”

Trotter also said that consolidation isn’t necessarily a “bad word.” There are many benefits for farmers who decide to consolidate, he said, from achieving lower production costs to allowing producers to have a better work-life balance by sharing the labor.

“I think it’s just keeping your eye on the ball and knowing where you’re going and understanding when you need to make some changes,” Trotter said.