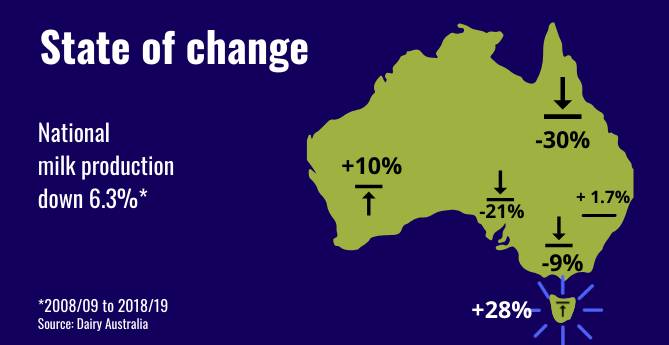

National milk production is at its lowest in a quarter of a century and forecast to shrink a little more again.

But what none of the statistics can measure is the way Australian farmers feel.

“Jaded, untrusting, negative, cynical,” is how prominent dairy farmer Daryl Hoey describes the prevailing mood.

What went wrong?

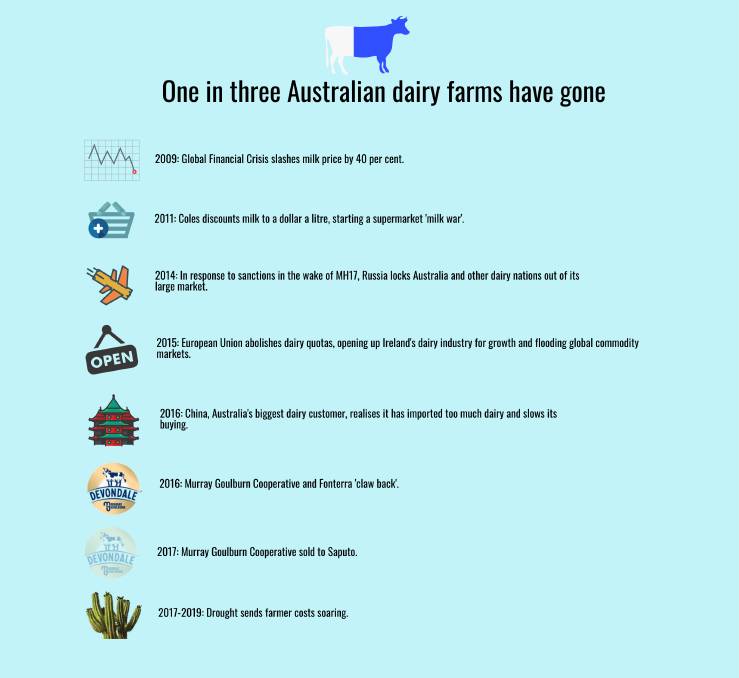

Like so many catastrophes, the dairy crisis was actually caused by a constellation of problems.

Australia is made up of several dairying regions, all with their unique pressures and there’s a very real distinction between those that send almost all of their milk to supermarkets and those whose milk is turned into other dairy products like cheese, butter, food ingredients or infant formula.

About 60 per cent of Australia’s milk is produced in Victoria and, while the portion of national dairy product that’s exported has fallen from 45 to 35pc since 2008/09, the price most Victorian farmers receive remains closely tied to global commodity markets.

For decades, farmer-owned cooperatives set the benchmark milk price and the last big one, Murray Goulburn (MG), dominated the processing landscape.

But, finding itself with ageing plants and short on capital, it hired former Sunrice managing director Gary Helou in 2011 to turn the cooperative around.

Mr Helou took big risks, partially floating the co-op, undercutting other processors to supply Coles ‘dollar milk’ and launching a suite of new products.

His timing was terrible.

When Australia joined other countries to apply sanctions after the shooting down of MH17 over Ukraine in 2014, the Soviet response was to ban our dairy products.

Then Australian Dairy Farmers president Noel Campbell described the Russian market as “not insignificant for dairy”.

“We exported around 22,000 tonnes of product, mostly butter, valued at $112 million in the past year alone,” he wrote.

“But the days are long gone of Australia first looking to Europe to buy our dairy produce.

“If there is some good news sitting alongside the bad, it is that Australian dairy products bound for Asia are fast becoming one of this country’s export success stories.”

Australian dairy was banking on China and the local and international rich list, including Gina Rinehart and Gerry Harvey, were racing to buy dairy assets as the pundits talked up ‘rivers of white gold’.

And then the Chinese economy softened, its warehouses chock-full of imported dairy product.

The price MG paid for milk became unaffordable and, in April 2016, it shocked farmers with a massive step down.

Fonterra followed a few days later, slashing its May and June milk price to $1.91 a kilogram of milk solids, about 14 cents a litre.

The suddenness and savagery of the cuts threw thousands of businesses into turmoil.

Many sold cows to abattoirs, dried them off and even shut down their dairies.

Both processors then made adjustments, with MG topping up farmer cashflows out of the co-op’s equity and Fonterra offering low-interest loans for desperate suppliers.

But the damage was done.

“That initial step down forced all those suppliers to take drastic action and some never recovered from it,” Mr Hoey said.

“Most farmers supplying other processors were not financially affected but no longer see the world or the industry in the same way they did before.”

In June 2017, MG made one last fatal error.

The processors to declare the new season’s price, it opened at $4.70kgMS, the equivalent of about 36cpl and well below the cost of production for most.

Despite a significant price rise before the season began, MG haemorrhaged supply and the once-proud coop was sold to Canadian processor Saputo later that very same year.

Dollar milk

The ‘fresh milk’ regions like Queensland, New South Wales and Western Australia were worst hit by the supermarket milk wars.

And, of those states, Queensland has done it toughest, with production down 30pc since 2008/09.

Queensland Dairyfarmers’ Organisation president Brian Tessmann said the ripple effect of discounted milk had been underestimated.

It had not only reduced the price of generic milk but, stealing market share from branded products, forced their prices down too.

“It ripped a huge amount of money from the supply chain and everybody who depended on it,” he said.

Mr Tessmann said the loss of production in Queensland had meant more milk had to be shifted from NSW and Victoria, leaving factories there underutilised and inefficient.

A lack of research investment in sub-tropical dairy pastures over the last 30 years had left Queensland farmers especially vulnerable.

Drought

Almost all the states were in drought during the last part of the decade. And even those regions spared the big dry suffered skyrocketing feed and water costs.

The impact is obvious in northern Victoria, the irrigation powerhouse, where the 2018/19 regional return on assets sits at -1.7pc according to the Dairy Farm Monitor Project.

Hope builds

The shockwaves have brought a recognition of the need for change.

Government responded with a mandatory Dairy Code of Conduct aimed at improving the relationships between farmers and processors, which takes effect from New Year’s Day.

Industry responded with the Australian Dairy Plan that is hoped to unite the entire supply chain and will be released in 2020.

Irrespective, Victorian farmer Daryl Hoey is optimistic about dairying.

“I know there’s always going to be ripples and there’s always going to be shocks in the system but I am actually positive,” he said.

“I’d like to think that we can start growing industry back to 10 billion litres and have more stability but it’s going to take a few things to fall in place for that to happen.”