Rep. Usher L. Burdick took the stage before hundreds of North Dakota farmers on the brink of strikes and riot on Sept. 14, 1932, and made a promise he couldn’t keep.

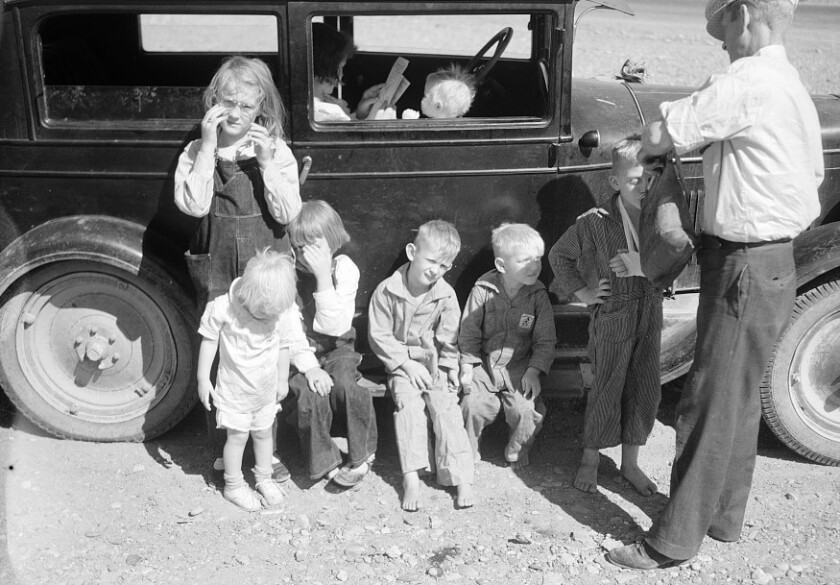

Surrounding North Dakota and Minnesota, all the way to Wisconsin, New York, Illinois and beyond, bankers were foreclosing on farmsteads ravaged by drought and locusts; milkmen weren’t making a livable wage.

Desperate farmers — like 47-year-old Henry Frazon — blamed the banking system. Out of frustration, Frazon shot and killed George Keup, a former vice president of the Farmers State Bank and the mayor of Columbus, North Dakota, on Sept. 17, 1932, in Keup’s money exchange office.

“Picketing shall be unnecessary, and if you will unite, if you will organize, if you will join hands with the farmers in Iowa and elsewhere, you will see your object obtained in 60 days,” promised Burdick, who was also president of the North Dakota Farmers Holiday Association, a chapter of the national organization intent on helping farmers boost produce prices.

Within days of Burdick’s announcement, headlines in The Forum and other newspapers predicted a “Full-fledged farmer war” in North Dakota, while “Milk war rumblings” stretched across at least 11 Midwestern states.

Picketers, known at times in the press as “holidayers,” began blocking highways with ropes leading to markets in St. Paul, Worthington, Minn., then westward into North Dakota cities like Bismarck, Williston, Minot, and Oakes.“They’ve got their backs to the wall, and faced with the prospect of losing their homes and their life savings, they’re ready to fight,” said Tolna, North Dakota farmer, Dell Willis, at the time.

Brandishing clubs and blocking roads with steel girders, heavy wire cables and spiked machine belts, farmer pickets went into action in Worthington on Sept. 19, 1932, and soon afterward lost in their first brush with the law after sending a truck full of sheep into a ditch.

Strikes slowed down grain deliveries in Williston, and by Sept. 22, “holidayers” had spread to 36 counties in North Dakota, effectively cutting off all entrances to Minot “24 hours a day,” said Chris Linnertz, secretary of Ward County Holiday Association.

And then, on Sept. 25, The Forum reported: “While farm strike enthusiasts through the middle west Saturday mustered their forces for a concerted drive to tighten their lines, the nation watched the spectacle of milk destruction to close down the supply in America’s largest cities.”

One newspaper headline read: “Milk Supply Destroyed” near Atlanta, Georgia. Milk producers in upstate New York threatened to stop shipments, which would aggregate millions of gallons daily lost to New York City unless rates were established to a “living minimum.”

Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, were on the brink of striking. “Milk holidays” continued among farmers in Ohio and Michigan.

Farm strike organizers bragged to The Forum that they had procured two million producers to clamp down on grain and produce markets, and that the movement’s influence had spread to Great Britain, where a general milk strike began in October 1932.

The movement then sailed across the North Sea to Norway, where fishermen dumped massive amounts of herring into the ocean, and in California “Thousands of tons of fruit into the Pacific ocean in order to maintain prices,” said T.T. Fuglestad, secretary of Farmers Holiday Association for Griggs County, North Dakota.

The strikes continued intermittently until February 1933, when strikers armed themselves with clubs and bombs, faced U.S. soldiers and the Chicago mob, and the so-called “milk wars” began.

Wisconsin terror

The Wisconsin Farm Holiday Association and the more radical Wisconsin Co-operative Milk Pool vowed to reduce supply and raise prices by withholding milk from the market, according to a 2018 research paper entitled “The Milk Strikes of 1933,” by Andrew Keene.

Strikes began in Feb. 1933 when more than 25,000 pounds of milk were deliberately tainted with kerosene. When some activists resorted to intimidation and violence to disrupt the supply of milk, the state called out the National Guard.

Troops responded with live ammunition. At least three farmers were killed in clashes among picketers, protesters and soldiers, and soldiers shot and killed one teenager while driving a car to assist a picket line.

By Nov. 1, the strikes took a more grisly turn. A creamery near Plymouth, Wisconsin, was bombed, causing massive destruction. That same day, a cheese factory near Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, was also bombed, causing minor damage to the building.

Later that week, a cheese factory near Belgium in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, was dynamited and burned. And a 60-year-old farmer was shot and killed by a stray bullet that had been fired at a picket line in the town of Burke, Wisconsin.

Milk riot in Fargo/Moorhead

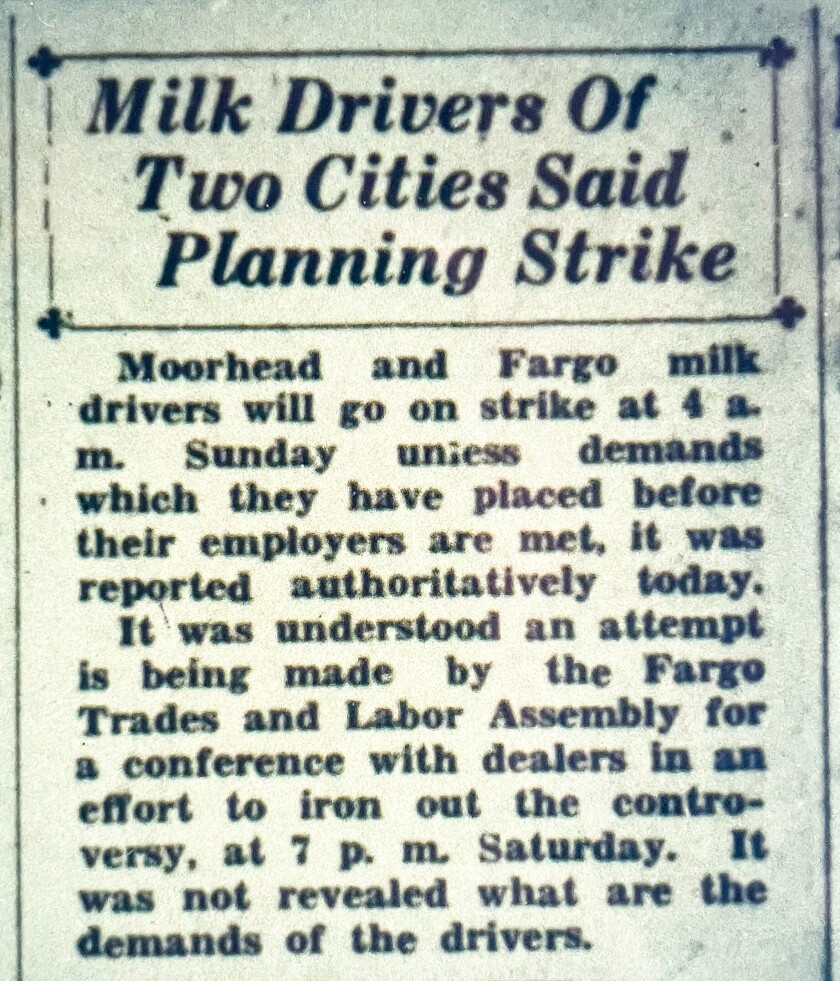

A year late to the “milk war,” Fargo unions held strikes in late 1934. Local newspapers caught wind of the intended milk strike two days before members of Chauffers, Teamsters & Helpers of Local Union No. 173 began at midnight, Nov. 4.

“Picketing, minor violence marks hectic Sunday, but temporary agreement reached,” a headline in the Moorhead Daily News reported.

The first strike order came after milk drivers voted to walk out. American Legion posts quickly erected emergency distribution stations in both Fargo and Moorhead, trying to get milk to neighborhoods with children.

Late on Nov. 4, a union organizer, Miles Dunne, “a leading figure in the Minneapolis truck strike” in 1933, and five others were caught tipping over milk trucks of dairy workers who didn’t comply, and pouring milk onto the streets, according to the Moorhead Daily News.

Six people were arrested and charged with inciting a riot, according to the Moorhead Daily News, but a book written by A.J. Muste and published in 1935 entitled “The New Militant,” reported the violence was much more severe.

Up to 10 “comrades” were in Muste’s room in Fargo following the late-night riot.

“The telephone rang. Miles Dunne was wanted. Fargo, N.D. was calling. The call was from a newspaper man in Fargo and conveyed the news that a few hours before the police force, which has (had) sworn in 300 special deputies in that town of about 25,000 inhabitants, had appeared at union headquarters with warrants…” wrote Muste.

The union men, or communist comrades, refused to give themselves up.

“So the police shot tear gas bombs through the windows, rounded up 94 strikers and threw them into jail… Thus our gathering was transformed into a council of war. Strike and defense plans were mapped out,” Muste wrote.

The Fargo Police Department told Forum News Service recently that they did not have records of the incident in police headquarters.

Headlines for the following two weeks made no further mention of violence. A 10-day truce was called after mediators stepped in. Talks nearly broke down at midnight on the final day, but negotiators, which included North Dakota Gov. Ole H. Olson, brokered a 5-day truce extension.

Even from a microfiche machine, scrolling through the newspaper pages published in 1934, the tension was palpable leading up to the final day.

‘Mob cheese’

In Chicago, the Italian mob still loyal to Al “Scarface” Capone, saw opportunity. Even though Capone was in prison for tax evasion at the time, his organization bought Meadowmoor Dairies in 1933.

Capone knew that the mob would be needing money because he believed President Franklin D. Roosevelt was preparing to repeal Prohibition . Once bootlegging and speakeasies became extinct, his revenue sources would dry up.

The mob began eyeing the dairies and the milk crisis.

Bullying its way into the milk business, the mob began undercutting dairy prices because they weren’t unionized, selling milk for 9 cents a quart, which was 2 cents below the regular price of other distributors. They extorted pizzerias into buying only “mob cheese.”

Capone’s political fixer, Murray “The Camel” Humphreys, then came up with an idea, according to the New York Times. He went to Steve Sumner, the union leader of the Milk Wagon Drivers’ Union Local 753, in 1933. He asked him to “lay low” so Meadowmoor could hire non-union workers to undercut other dairies.

In return, the union would receive the mob’s protection, and Sumner and his union drivers could protest Meadowmoor, which would give Meadowmoor reason to raise milk prices again.

Sumner refused. The beginning of Chicago’s 18-month-long milk war began and culminated into numerous bombings with trucks destroyed and vendors beaten.

Communist propaganda

While many of the strike organizers, including some elected officials across the state were reportedly pushing socialist agendas at the time, a schism between strikers occurred in North Dakota after “Reds” infiltrated the Holiday movement.

Headlines at the time read:

“Williston Farmers Quit Picketing; Claim Communists Active.”

“Reds at Work in Farm Strike.”

Charged with organizing pickets around Williston farm market highways without official recognition by the North Dakota and Williams County Farm Holiday associations, farmers broke away from P.K. Barrett of Sanish, North Dakota, a communist candidate for Congress, and L.J. Dahl of Sioux City, Iowa, also a communist, who was giving out picket instructions.

“Holidayers” became “enraged,” saying they had been “duped by outsiders,” and quit.

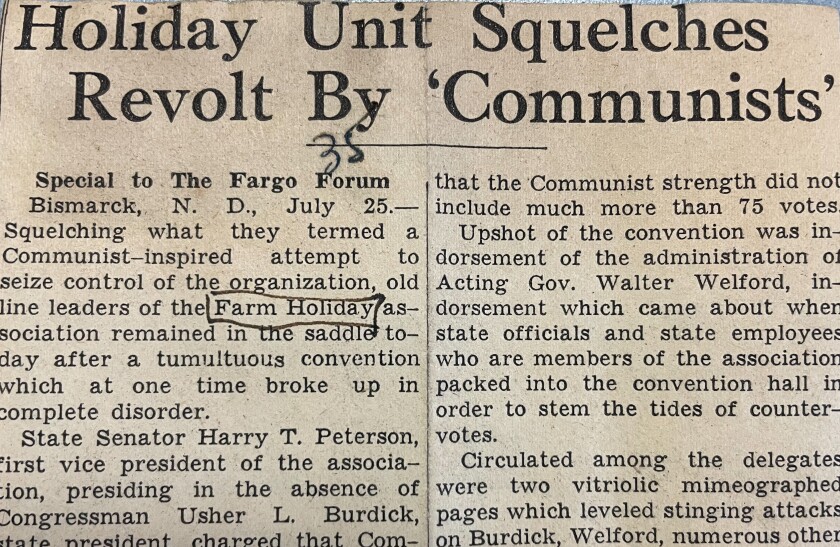

The Farm Holiday Association also “squelched” what they termed a Communist-inspired attempt to seize control of the organization, and kept “old-line leaders” remaining “in the saddle” after a tumultuous convention that at one time broke up in complete disorder.

State Sen. Harry T. Peterson, first vice president of the association who presided in the absence of Rep. Usher L. Burdick, charged that communists attempted to pack the meeting to sway votes. Communist strength did not include much more than 75 votes.

At the time, communists circulated their own weekly newspaper called the “Iconoclast,” and they repeatedly attempted to take over the Holiday leadership. In another takeover failure, “two vitriolic mimeographed pages which leveled stinging attacks” against Burdick, and other leaders of the Holiday association, were circulated.

Accusations included: “farming the farmers,” they were “reactionary” and guilty of “nepotism,” and that people were hiring “Negro help”

At the same time, the Holiday Association in North Dakota sponsored bills and tried to push legislation that many considered to be socialist, even vigilante in nature. On July 19, 1934 Burdick introduced legislation that would have immunized the poor against crimes.

“If and in the event a man needs food and clothing for his family, and such be not forthcoming from federal, state or local relief agencies, he can go out and get it and be protected against criminal prosecution,” said Burdick during a street corner speech in Bismarck.

He also proclaimed a legislative program that included a five-year moratorium on all property mortgages under which there would be no foreclosures “with interest at the rate the international bankers pay the government, which is nothing.”

End of the milk wars

From “Black Thursday,” or the stock market crash of 1929, to the Dust Bowl, to the milk wars and farm strikes to Roosevelt’s New Deal, overturn of Prohibition, the Social Security System and more, the Great Depression didn’t truly end until 1941, when America entered World War II, according to Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Most of the milk wars, while violent, sizzled out in 1934.

In Fargo, strikers and mediators came to an agreement. After 15 days of secretly-held heated discussions, “The Fargo-Moorhead milk strike ended,” the Moorhead Daily Times reported.

The agreement became known as the “Milk code,” which stated drivers and salesmen were entitled to $20 a week with 4% commissions; wholesale drivers received 1.5% commissions, and inside worker wages saw a boost to $18 a week. Truck drivers, some of the most vocal strikers, saw their salaries boosted to 40 cents an hour.

But the violence didn’t stop with the milk code.

In early December, the Frank O. Knerr Dairy Company was picketed. Roofing tacks were strewn throughout the property. Employees who didn’t strike were targeted.

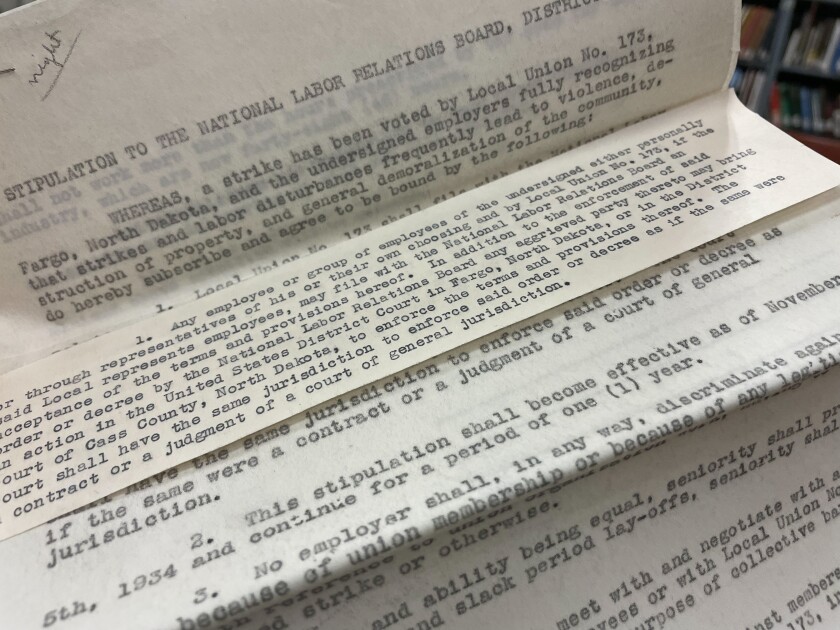

According to testimony discovered within the North Dakota State University Archives, the Fargo Trades and Labor Assembly warned the dairy company that they were out of compliance with the milk code agreement.

When owner Frank Knerr didn’t agree, strikers attacked, court documents stated.

Charles Elgin, a driver for the dairy company, was delivering crushed ice to the John Holzer Confectionary store on Broadway on Dec. 10. From out of the shadows, two men emerged, striking him on the right temple and knocking him to the ground. It was dark out, and the assaillants escaped discovery and the police, who gave a short pursuit.

The next day, J. Haas was preparing to go to work at the dairy when union workers found him, threatening him that if he didn’t quit some “radical would pop him off.”

On Jan. 6, 1935, Alice Knerr, vice president of the dairy company, discovered sugar had been poured into the gas tank of her car.

Late at night that same day, Melvin Sexton and James Colby were delivering empty cream cans when three men came out from behind boxcars at the Great Northern Railway Station.

“Heave on her boys,” Sexton testified he heard before the assailants tipped his milk truck over.

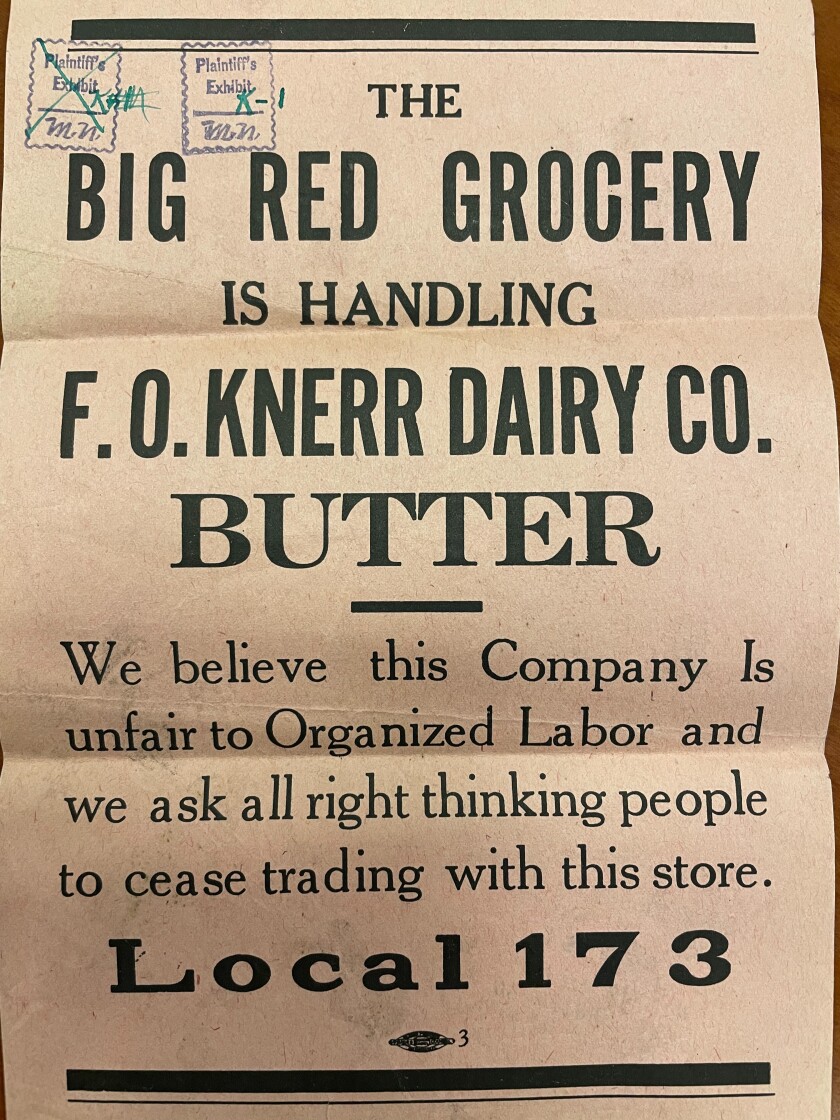

And in January 1935, union members discovered that the Big Red Grocery was purchasing Knerr dairy products, and began a campaign to stop customers from going to the store.

Saying he had suffered damages exceeding $1,000, Knerr sued Chauffers, Teamsters & Helpers of Local Union No. 173, the Fargo Trades and Labor Assembly, Miles Dunn, (sometimes spelled Dunne), W.N. Lind and others, saying that he was operating under a “Butter code,” not under the milk code that was part of the milk strike arrangement.

Defended in court by a young Quentin Burdick, future politician that would come to be known as “The King of Pork,” the defendants were ordered to pay $141.95 in damages, and all charges against the defendants were dropped, according to existing court documents.

In Wisconsin, farmers felt defeated after repeated attempts at strikes to raise milk prices, and . Roosevelt’s New Deal also approved living conditions for milk farmers, and many strikers returned home in 1934.

In Chicago, mass arrests in the late 1930s and a government agreement in 1940 with farmers’ organizations and unions to halt tactics such as price fixing and hampering with store sales of milk, ended the milk war.

By the time Capone was released from Alcatraz in 1939, he was suffering from a severe case of syphilis and died in his Florida mansion when he was 48 years old.

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K