Dairy farmers are dumping the stuff, as some call for culling cows.

Milk is “indispensable for a healthy China and a strong nation”. So said officials in 2018 when they launched a campaign to supercharge the country’s dairy industry. They wanted to boost China’s food security by cutting its reliance on imported milk. At the same time, they hoped that the Chinese would become fitter by consuming more dairy products, which are rich in protein and calcium. Officials gave farmers subsidies to increase their herds of cows.

They urged state propagandists to “nurture the habit of consuming dairy products”.

The campaign has achieved some of its goals. Since it began, China’s milk production has risen by a third. Last year the country’s cows yielded 42m tonnes of the stuff, surpassing a government target two years early. But the public has not fallen in love with milk. The average Chinese person still consumes only about 40kg of dairy products a year. That is a third of the global average and less than 40% of what China’s health authorities recommend.

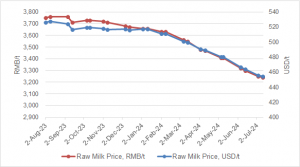

Because production has outpaced consumption, China’s dairy farms are awash in unwanted milk. As a result, they have been forced to lower their prices by 28% since August 2021 (see chart). At the end of September, one kilogram of raw milk sold for 3.14 yuan (45 cents) on average. That is below the cost of production for many farms. Most have been losing money since the second half of last year, reckons Lu Shi of StoneX Group, a financial-services firm.

Why aren’t Chinese people consuming more dairy products? For a start, many are genetically predisposed to be intolerant of lactose, a sugar found in milk. Outside areas like the Mongolian steppe, where nomads have long herded cattle, dairy products are not a big part of traditional Chinese diets. In the 19th century some Chinese were shocked by the love of milk displayed by visiting Westerners. “In many places our practice of drinking it and using it in cooking is regarded with the utmost disgust,” wrote an American missionary at the time.

These days Chinese parents are much more likely to tell their children to drink milk. Dairy companies sponsor the country’s Olympic athletes. But dairy products have not become staples. Chinese consumption is largely limited to milk and yogurt. Butter and cheese, which account for lots of milk production in other countries, are unfamiliar in many parts of China. Most people still “don’t understand the culture of cheese or how to appreciate it”, grumbles Liu Yang, a cheesemonger in Beijing.

Chinese people are even less likely to buy exotic foodstuffs at the moment because of the ailing economy and its effect on incomes. Meanwhile, a baby bust has reduced demand for infant formula (made from cow’s milk).

When Chinese firms produce too much stuff for the domestic market, they often export it. But selling Chinese dairy products overseas is tough. Because China has to import much of its cattle feed, the cost of production is high by international standards. Chinese dairy products have a poor reputation, too. Memories linger of a scandal in 2008 when Chinese companies were found to be adding melamine, a dangerous chemical, to their milk powder. Six babies died and hundreds of thousands fell ill.

All this leaves Chinese dairy farmers in a bind. Some are reportedly dumping milk. The state is trying to help by encouraging banks to extend more loans to farmers and to accept cattle as collateral. Officials have also called for raising public awareness of the health benefits of dairy products. But Li Shengli of the China Dairy Association thinks the problem is too many cows. In comments published by state media last month, he called for culling 300,000 of them. ■

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K