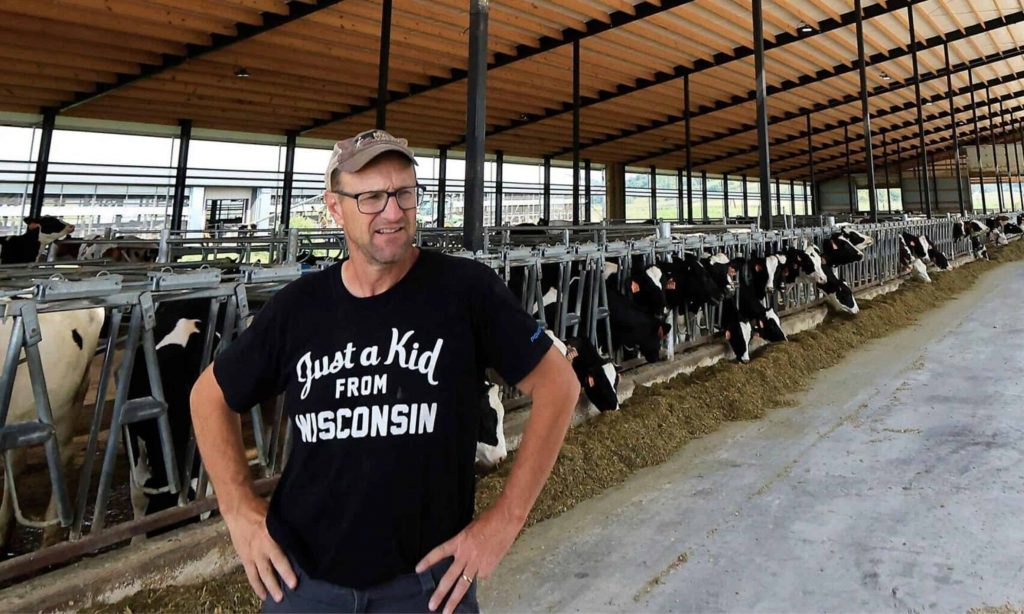

The Breunig family still milks cows — 500 of them — as it has for three generations. Mitch Breunig is teaching his son how to farm so he, too, can carry on the family’s legacy.

Mystic Valley Dairy owner Mitch Breunig uses a robotic feed pusher on his farm in Sauk City. Technology is increasingly reducing the need for labor for farmers, if they can afford it.

JOHN HART, STATE JOURNAL

But the way the Breunigs farm has changed dramatically, thanks to new technology that gives them and farmers around the world more information and makes the industry more efficient — for those who can afford it.

Cows can now wear Fitbit-like devices as collars or ear tags that monitor their eating, movement, breathing and rumination, the natural process by which cows regurgitate previously consumed food and then chew it further for better digestion. Robots push feed into pens to help them stay nourished and can milk cows with no human labor needed.

Data, rather than anecdotal evidence, is driving the decisions dairy farmers make daily, especially in Wisconsin, which produces the second-highest volume of dairy products in the nation, behind California. The state leads in the production of cheese, is home to over a million cows and generates $45 billion for the economy annually, according to the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection.

“It’s not your grandpa’s farm any more,” Breunig said. “When you’re in the moment, you don’t even realize it, but when you step back and look at the way you’re able to do things much more effectively, it’s amazing.”

Data-gathering tools and other innovations in the dairy industry will be on display Sunday through Oct. 6 at the World Dairy Expo in Madison. The event at the Alliant Energy Center brings in more than 500 vendors and 50,000 attendees.

Wearable technology, in particular, has had a big impact on the dairy industry, enabling farmers to monitor all their livestock all at once, at all hours of the day, Breunig said. The software senses cows’ breathing patterns or rumination levels, records the information and gives the farmer a report on the animals’ behavior or health. If a cow is exhaling more heavily than normal, it could be too hot, or if it’s not ruminating sufficiently, it could be sick. If a problem arises with a cow, Breunig receives an email alert.

The reports update every 20 minutes at Mystic Valley Dairy. Breunig can see the data on his smartphone and know when cows have a higher likelihood of becoming pregnant or are low on calcium, he said.

“Time is fixed. This enables us to use our time the best way,” Breunig said while walking through rows of cows. “It allows us to target the cows that need help.”

Positive signs

Since installing wearable technology, in addition to a robot that pushes feed into a cow’s pen to keep them nourished, Mystic Valley Dairy has increased its dairy output, raised cow pregnancy rates by over 10% and reduced labor costs, Breunig said.

“Before, you had 20 cows, and they’d run all over the pasture. You never missed a day at work because you did it all yourselves,” Breunig said. “Now, we’re easily able to have more cows, give them comfort, so they’re happy and healthy. We’re able to manage much better than it was 20 years ago.”

If implemented effectively, connectivity in agriculture — the ability to share information and data across platforms — could add more than $500 billion to global gross domestic product by 2030, according to a report issued by McKinsey & Company in 2020.

The rise in output could help meet the world’s growing nutritional needs. The global population is slated to creep up to nearly 10 billion by 2050, which would translate into a need of 70% more calories to feed the world sufficiently, the same report found.

Size matters

Dr. Jeffrey Bewley is the dairy analytics and innovation scientist at the Holstein Association, the world’s largest dairy cattle breed organization, which has over 20,000 members and supports research on the dairy sector.

Bewley said connectivity could have the power to revolutionize the way farming is done, but he anticipates changes will differ depending on farm size. Larger farms, the ones with the funds to pursue capital investments and more animals to spread fixed costs across, will likely be the ones able to adopt new technologies first.

Small and mid-size farms, already challenged by rising production costs and globalization, may face more barriers to technological adoption. The majority of the 700 farms Wisconsin lost between 2017 and 2021 were from the lowest sales class bracket, a metric that combines agricultural product sales and government program payments, according to USDA data.

But, farms occupying the lowest sales class, $1,000 to $9,999, still constitute the largest percentage of total farms in Wisconsin of any sales class group, which goes up to one million and over.

Bob Wills, the owner of Cedar Grove Cheese, an artisan cheese shop and producer in Sauk County, said farm technology is not feasible for all farmers.

“These technology solutions have potential value in some situations, but they probably would not be profitable or practical on the farmers that we buy milk from,” Wills said.

Still, a risk

One challenge that emerges for farms of all scales is knowing what technology to buy. In an industry known for volatile pricing and irregular profitability, many dairy farmers say they need to be extremely confident a product will deliver a return on investment before making a purchase.

“I’ve had technologies on my farm fail,” Breunig said, referring a device that he tried that was supposed to detect lame leg but gave false diagnoses on pregnant cows. “We really have to find those investments that really make a difference then go all in.”

A dairy farm can be a harsh environment for technology. Cows move around a lot and weather can be extreme, especially in Wisconsin, and many companies that sell these products do not allow farmers trial runs due to the complexity of installation. So, farmers need to seek certainty in their decisions, whether that be heavily researching a product, chatting with friends or reading honest testimonials.

A collar or ear tag cows generally cost around $100 each and are expected to last 5 to 7 years. Meanwhile, a single, labor-free robotic feed pusher is about $25,000 and services around 300 cows.

However, even if costs decreased, heightened technological adoption may not necessary follow, said Dr. Marcia Endres, a professor and researcher in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Animal Science.

Beyond money

There are other considerations on dairy farms outside of costs, such as how much training farmers need to employ these tools and consumer sentiment about machines, Endres said.

Plus, agriculture technology companies may want to keep costs elevated for to further fund research and development initiatives and create novel tools, Endres said.

“I don’t think this technology will ever be very cheap due to the costs of research and development,” Endres said. “But, who knows, I don’t have a crystal ball.”

But, if the technology functions well for an appropriate cost to businesses, it can pay big dividends over time, greatly reducing operating costs and working in tandem with farmers.

Crunching data

Yasir Khokhar is the founder and CEO of Connecterra, a growing agricultural technology company based out of Amsterdam with operations in Wisconsin. Connecterra is building a platform that aggregates, organizes and interprets data on a dairy farm onto one single platform. With this information, farmers can make more informed decisions and then measure their impacts.

The Connecterra platform is currently being tested and used on dairy farms nationwide, including in Wisconsin, and is free to farmers who partner with the company. Khokhar said he wants to refine and perfect the product before working to expand its market share, ultimately developing an interface with no data on it all, just applicable conclusions for users.

“We’re at a very interesting inflection point,” Khokhar said. “Because of all the challenges that the industry faces — labor, climate change, productivity, sustainability — a lot of these challenges need to be solved. Technology can help.”

Regarding the near future of technology and dairy, Bewley said he likely sees two main developments unfolding: the continuation of looking to other industries, such as human medicine, to reverse engineer technology for cows, and the betterment of pre-existing software.

It’s important to develop new gadgets, Bewley said, but it’s also vital to ensure they can actually be implemented by farmers.

“We should always dream big when it comes to what we can do with technology,” Bewley said. “It will be exciting to see what continues to happen as we move forward.”