After a developer began eyeing rural northwest Wisconsin for a large swine farm, five small towns enacted ordinances aimed at curbing environmental and health impacts.

Then, the state’s biggest business and agricultural interest groups fought back. They engaged disaffected residents. Some locals sued. Others ran for political office. New leaders in one Polk County town rescinded regulations on concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs.

Now, officials in the remaining towns with livestock regulations wonder whether they, too, are in legal crosshairs.

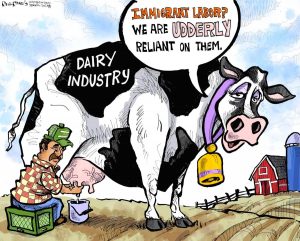

The Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation and Wisconsin Dairy Alliance have filed a far-reaching public records request for documents from an advisory group that shaped the municipalities’ CAFO rules.

In 2019, a developer proposed an operation, known as Cumberland LLC, that would have housed up to 26,350 pigs — the region’s first swine CAFO and what would be the largest in Wisconsin. Residents later formed the advisory group, believing that state livestock laws insufficiently protect health and quality of life.

In October, two farm families, represented by WMC Litigation Center, sued one municipality in the advisory group: Laketown, population 1,024. The town’s livestock, crop and specialty farms make up almost two-thirds of the landscape.

The plaintiffs, later joined by the Farm Bureau, argued that Laketown’s ordinance diminished property values and prospects for future expansion, a government overreach that could “essentially outlaw mid-to-large sized livestock farms.”

Scott Rosenow, the Litigation Center’s executive director, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

The records request follows the dismissal of that lawsuit, but some residents wonder if the lobbying organizations are “fishing” for another case, the latest effort to prevent local governments from regulating farming in America’s Dairyland.

Pig farm proposal roils northwest Wisconsin

Cumberland’s proposal sparked heated public meetings, dozens of letters to newspapers and the formation of a nonprofit opposition organization.

The CAFO would be constructed in Trade Lake, north of Laketown in neighboring Burnett County. Sows would be bred and piglets trucked elsewhere after weaning, where they would grow until slaughter.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources rejected Cumberland’s application in March. The developer recently pitched a scaled-down project that would house 19,800 swine.

CAFO opponents in Laketown include back-to-the-landers, who view such farms as inhumane to animals. Others fear the health impacts of the millions of gallons of manure facilities generate annually, to be spread on farm fields.

About 90% of all nitrate groundwater pollution in Wisconsin comes from fertilizer and manure application, according to the DNR. The naturally occurring nutrient helps crops grow, but scientists associate exposure in drinking water with birth defects, thyroid disease and increased risk of developing certain cancers.

Other concerns are rooted in economics. Some Laketown farmers say CAFOs threaten smaller operations; others fear shrinking property values.

“It’s nothing more than big corporations getting together with the government and putting the screws to the little people,” said Vietnam Army veteran and recently ousted Laketown supervisor, Bruce Paulsen, who, like many opponents, speculates that the pork will be exported to China.

Laketown’s ordinance explained

The town ordinances regulate not where, but how CAFOs operate.

Laketown’s rules applied to new operations housing at least 700 “animal units,” the equivalent of 1,750 swine or 500 dairy cows, and required applicants to submit plans for preventing infectious diseases, air pollution and odor; managing waste and handling dead animals.

It also mandated traffic and property value impact studies, a surety for clean-ups and decommissioning and an annual $1-per-animal-unit permit fee — atop costs to review the application and enforce the terms of the permit.

The ordinance did not affect existing livestock facilities as long as the farms did not change owners, alter their animal species or expand beyond 1,000 animal units. But several residents believed the strict requirements amounted to a CAFO ban that would bar existing farms from growing.

Others protested government spending on the advisory group. Some said the smell of manure comes with living in a rural area.

Polk County Supervisor Brad Olson asked why farming gets blamed when excessive road salt and wastewater treatment plant overflows also taint water.

“I don’t think anybody denies that agriculture is part of the problem — or has the potential to be part of the problem in pollution,” said Olson, who farms crops and used to be a dairy farmer. “If we’re going to look at pollution, let’s look at the bigger picture.”

Clothing-optional campground owners Jen and Scott Matthiesen initially signed onto the lawsuit before attorneys requested they withdraw out of concern their business — “we’re not a nudist camp,” Jen said — would distract from the case. The couple worried that singling out farming could pave the way for special regulation of other businesses.

New Laketown Sup. Ron Peterson ran on the promise of overturning the ordinance. He believes it unlawfully superseded state laws. Those laws ban local authorities from regulating livestock more strictly than the state — unless they can prove a need to protect health or safety.

“The Wisconsin Legislature has been very clear in the statute that it’s their intent that they want uniformity in the regulation of animal agriculture,” said Peterson, a former attorney.