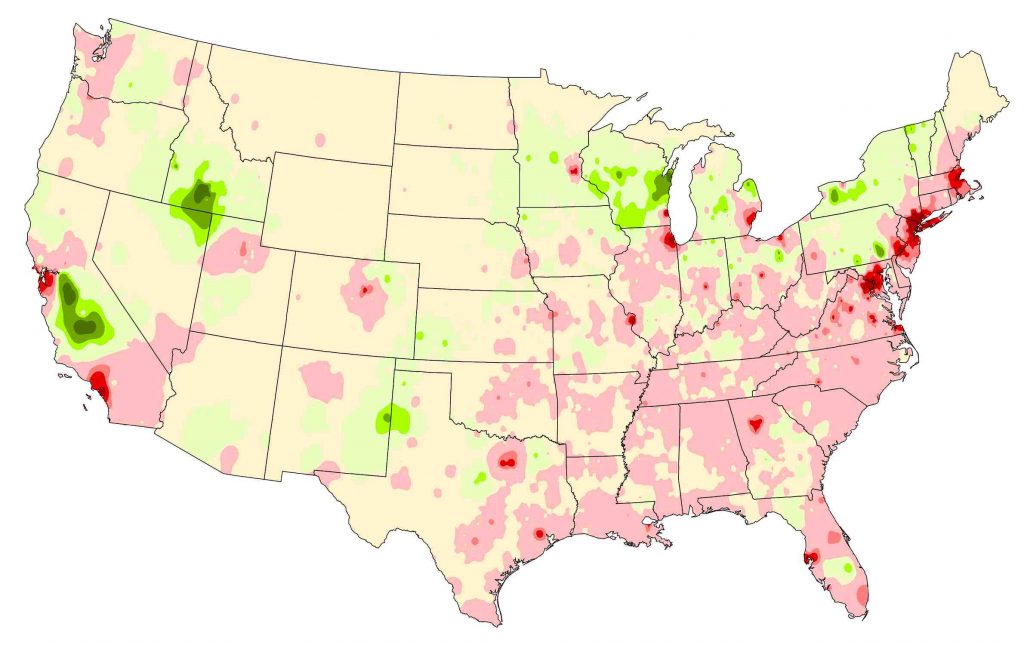

A stubborn slump in milk prices is hammering Wisconsin’s dairy industry. In 2015, prices plummeted, and have yet to recover. In 2018, the state lost dairy herds at a record-breaking pace, and led the nation in farm bankruptcies.

While the economic and human toll wrought by low milk prices have been documented, the factors that determine those prices can feel enigmatic or perhaps even baffling for people outside of the industry — and perhaps for those within as well.

Indeed, a dairy processors trade organization referenced the complicated American milk pricing system in a “Milk Pricing 101” lesson for its members: “There is an old joke about a senior-level USDA person testifying to Congress on dairy policy and milk pricing. He said there are only three people that understood it and two of them are lying.”

Hyperbole aside, the regulatory and market systems that determine the size of farmers’ monthly milk payments are indeed complex. To help demystify how milk prices are determined, Wisconsin-based dairy economists provide a crash course in the history and unique economics of milk pricing in the United States.

Dairy farmers are vulnerable to becoming price-takers

Just like any other business, to remain viable over the long term, a dairy farm must maintain enough cash flow cover expenditures. However, milk’s unique qualities complicate this basic business necessity.

Milk stands out from other agricultural products in three ways. One, milk has to be harvested 365 days a year given the biology of cows. Two, it spoils quickly, and requires refrigeration to extend shelf life. Three, at 85% water, milk is bulky and expensive to ship long distances.

These factors have historically made dairy farmers vulnerable to becoming “price-takers,” according to Mark Stephenson. He is director of the Center for Dairy Profitability at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and also chairs Wisconsin’s Dairy Task Force 2.0, a group assembled by former Gov. Scott Walker to address the ongoing industry crisis.

A price-taker is someone who lacks bargaining power in a marketplace and therefore has to accept the price dictated by those in power. Unlike other producers, who can sometimes sit on their harvest and hope for higher prices, or ship it to more lucrative markets, dairy farmers generally have little choice but to sell their milk immediately to a local processing plant at the price it offers.

Prior to the 1930s, Stephenson said this vulnerability led to what he called “destructive competition,” whereby dairy processors sought to increase their market share by lowering prices, to the detriment of farmers.

As a milk processor, “it’s pretty hard to distinguish my product from my competitor’s product,” Stephenson explained. “Why should it get a better price? The only way to sell more is to sell mine at a lower price than yours.”

Because processors have some market power over farms, prior to regulations they were able to dictate lower prices in an effort to increase market share. Without a different buyer for their milk and with no one to pass a price cut onto, farmers were faced with a lower income.

This destructive competition first became a problem in the U.S. dairy industry during the late 19th century, and in turn spurred dairy farmers to form cooperatives to restore a semblance of power in price negotiations with processors, Stephenson said. But these cooperatives found only limited success, and by the 1930s global economic pressures and ongoing destructive competition sent milk prices into a downward spiral.

“That’s why we got [milk pricing] regulation in this country,” said Stephenson. “When agriculture was really taking it on the chin in the Great Depression, there were real ideas that maybe government could do something.”

Those ideas culminated in the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act of 1937, which provided the foundation for the federal milk pricing system still used to this day.

To ensure the viability of dairy farming, this act of Congress authorized the U.S. Department of Agriculture to set pricing rules to encourage more order within the industry. Those rules have evolved over the decades, but their basic intent has remained constant.

Encouraging order in a volatile industry

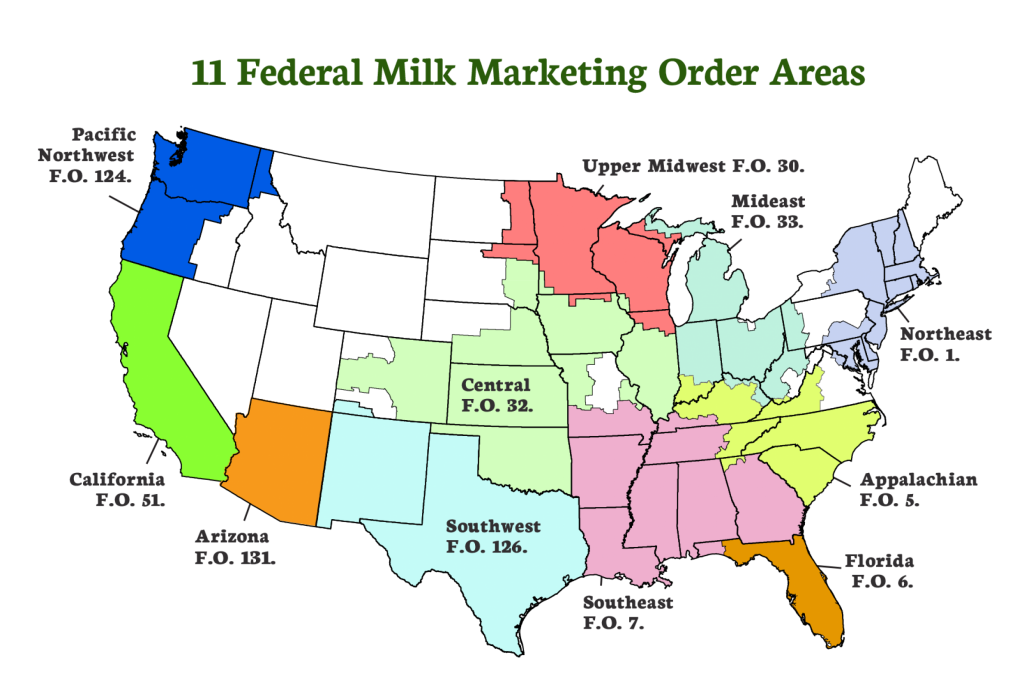

Today, federal rules establish a classified pricing structure for Grade A milk based on end-product, meaning raw milk that is processed and eventually winds up in a jug is priced differently than milk that is processed into cheese or ice cream. Grade B milk, which does not require the same set of sanitary conditions as Grade A, cannot be used for fluid consumption and is not regulated by this USDA’s price system. These rules also establish price pooling within most major dairy regions in the country, which are known as Federal Milk Marketing Orders, or FMMOs.

Because milk is processed into broad product classes with varying demand and manufacturing costs, federal regulators have established four pricing classes for Grade A milk: Class I is milk for fluid consumption, including buttermilk and eggnog; Class II is soft products, including yogurt, cottage cheese and ice cream; Class III is hard cheeses and cream cheese; and Class IV is butter and dry products, including milk powders.

The proportion of milk processed into the four classes varies by FMMO region. These regulatory regions are structured around fluid milk markets, so those where demand for fluid milk is high compared with its supply generally produce more Class I milk. Most of Wisconsin is within a fluid milk surplus region, and has historically supplied much of the nation’s cheese.

Milk for fluid consumption usually gets top dollar, Stephenson said, partly because of demand, but also because fluid processing plants have more variable needs and are therefore more expensive accounts to service. On the other hand, cheese plants usually receive a break on prices because, among other factors, their needs are less variable. Cheese processors also often take milk at times when fluid plants won’t, like weekends and during periods of surplus local production.

Only a few products determine the value of milk

The USDA calculates the minimum price for each class of milk based on the value of the milk’s component parts needed to make the various end-products. Those components include butterfat, protein, nonfat solids and other solids.

The USDA estimates the value of those components through a highly structured process, which changes occasionally but has remained more or less the same since the early 2000s, Mark Stephenson said.

The process begins with weekly surveys of dairy processors, who must report the wholesale prices they receive for several standard products considered indicative of the value of each component.

For instance, the USDA has deemed the wholesale market price for butter as a good gauge for determining the value of butterfat. Meanwhile the wholesale market price for cheddar cheese dictates the value of milk protein. Nonfat dry milk prices are a proxy for the value of nonfat solids, and dry whey prices indicate the value of other solids.

Regulators average the wholesale price surveys within each FMMO on a monthly basis. They then plug those wholesale averages into calculations that also take into account the proportion of each component in a given amount of milk — known as the component’s yield factor — as well as the cost of processing. Those calculations result in a monthly value for each component part, and those values are plugged into further calculations that determine the minimum price for each class of milk.

Impact of export markets

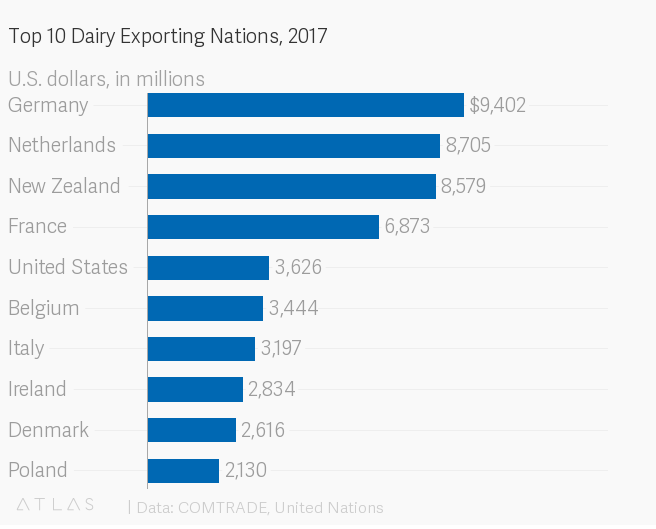

International demand for dairy products plays a significant role in determining milk prices, particularly in recent decades.

“Exports play a big role,” Mark Stephenson said. “It used to be that 3 to 4% of our milk production was exported, and now we export 15 to 17%.”

With this increased dependence on the global market, when international demand for American dairy products falls, as it did during the Great Recession and again in 2015, milk prices generally fall as well.

“Export markets are key to the viability of the U.S. dairy industry,” said Brian Gould, an expert on dairy pricing and professor emeritus of agribusiness in UW-Madison’s Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics. “If you lose those export markets, everything gets driven down.”

Indeed, the milk price fell rapidly in 2015 as American producers began losing market share to producers in Europe and New Zealand, Stephenson said. Ongoing trade wars have aggravated the export slump, he added. American farmers have been further sidelined as major dairy export markets like Canada, China and Mexico retaliate to American-imposed tariffs on raw materials like aluminum and steel by setting their own tariffs and restrictions on other goods, including milk products.

With lower international demand coinciding with growing production, commodities like cheese are piling up in the U.S. and contributing to lower milk prices.

“There are a host of reasons as to why [exports are down], but the bottom line is we haven’t been exporting as much as we need to,” Stephenson said.

Selling milk to make cheese

For a number of reasons, not least of which is Wisconsin’s longtime status as a region with a large milk surplus, most the milk produced in the state is processed into Class III hard cheeses, which can be stored and shipped to distant markets.

“Eighty to 90% of the milk produced in Wisconsin goes to cheese, so Class III is important here,” said Brian Gould.

However, this use doesn’t mean individual Wisconsin farmers who sell milk to cheese processors receive lower prices than they would if it were processed for fluid consumption.

Instead, each FMMO pools the dollars that all participating processors pay for Grade A milk on a monthly basis. Farmers receive a blended price reflecting the average amount those processors paid for milk over the last month. Only Class I fluid milk processors are required to participate in the FMMO pools, but Mark Stephenson said most Class II, III and IV processors also opt in because the pools allow them to pay higher prices to farmers without having to cut into their own profits.

A simple example to illustrate how price pooling works is to imagine an FMMO where 50% of the milk is sold to Class I fluid milk processors who pay $20 per hundredweight (cwt), and 50% is sold to Class III hard cheese processors who pay $18 cwt. The blended milk price in that FMMO would then be $19 cwt, and Class I fluid milk processors would pay $19 cwt directly to farmers and contribute $1 cwt to the FMMO pool. Class III processors can draw from the pool so their farmers also receive $19 cwt.

Other factors affect the price of milk, such as the distance between where Class I milk is sold and areas of surplus supply. Also, the USDA only regulates a minimum price for milk, with some processors paying more, including a premium for organic milk. But market changes in the organic industry are causing problems for Wisconsin’s organic dairy farmers too.

Several dairy-producing regions around the U.S. also operate outside of federal pricing system, which only applies to areas where a majority of farmers have opted into it. These regions are instead subject to state regulations.

How the system could change

The rules governing milk prices have changed over the decades, and both Brian Gould and Mark Stephenson predict more changes in the near future.

“The USDA expects to go to a hearing again sometime this year or next year,” Stephenson said. “It’s partly the current situation [in the dairy industry] and partly because the rules haven’t changed in a long time.”

Any potential hearing about regulatory changes would be open to the public, Stephenson said, and anyone would be able to provide input directly to USDA officials. He added that law stipulates the USDA can only draw from ideas entered during those public hearings when considering updates to regulations.

Gould said he would like to see the USDA better address overproduction.

Improving technology and genetics, and the decisions of thousands of dairy farmers have led to record milk production in Wisconsin and the U.S. just as market demand has slowed. Gould pointed to production rules in Canada as a possible framework for American regulators.

Stephenson agreed with Gould that the USDA would do well to find a better way to help farmers manage supply, though he did not endorse the Canadian supply model and considered it difficult to implement in the U.S.

“We could consider alternatives to coordinating the supply chain,” he said. “We had in the past 40,000 independent decision-makers, and when milk prices are high like in 2014, that’s a market signal that the market wants more milk … well, 40,000 individual decisions flooded the market. Maybe we can coordinate that better.”

Gould would also like the USDA to consider reevaluating the products it uses for pricing milk components.

“There’s been a tremendous increase in dairy products,” Gould said. “When you have a commodity-based pricing system, and you use just a few commodities to help set prices, is the value of milk really reflected in that price?”

Gould singled out cheddar in particular, given its importance to Class III pricing and the Wisconsin dairy industry. He suggested the USDA look into pegging milk’s protein value to another product or multiple products.

For his part, Stephenson said he didn’t think changing the commodity pricing structure would have that great an effect on milk prices.

“Right now, cheddar is kind of our currency in cheese in this country. It isn’t as though that’s the only cheese product we make or the largest volume, but it provides at least a beacon for prices,” he said. “We need something that reflects changes in the market’s valuation of products — I’m not suggesting that we move or not from cheddar, but I think it’ll be awhile before we get there.”