It was Oct. 8, 2018.

In the parking lot at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, three of Roecker’s friends were discussing what had happened that day to Statz, whose dairy farm was a few miles from town.

Roecker broke down and cried.

“You guys just don’t know what it’s like dealing with this,” he told them.

Roecker, who is also a dairy farmer, understood the severe depression that Statz experienced when his farm was in trouble. He’d been through it himself.

“You have this burden that you carry,” he said. “I kept feeling all the time that I was a failure, that I had let everybody down.”

Some parishioners at St. Peter’s, where Statz was a member, knew he was battling depression. But since he was receiving out-patient treatment, they assumed he wasn’t at risk of dying from suicide.

Statz had suffered from depression for years. He felt deeply responsible for keeping his third-generation farm afloat through hard times – including the dairy crisis triggered after milk prices collapsed in late 2014.

In his mind, difficulties on the farm would quickly slip from “bad to catastrophic,” said Brenda Statz, his widow and wife of 34 years.

She and Leon hadn’t lost their farm, but they had struggled some as they transitioned from dairy to beef and grain farming. For Leon, the change represented a huge failure.

“He would say, ‘I’m a dairyman, not a grain farmer,'” Brenda recalled.

This year alone, about 800 dairy farmers in Wisconsin quit or were forced out of the business, a rate of more than two per day. Some left in despair, having lost not only their livelihood but the home they grew up in, which their parents or grandparents had built.

“You feel like you are letting down all the previous generations of your family if you don’t farm anymore,” Roecker said.

Success can be costly, stressful

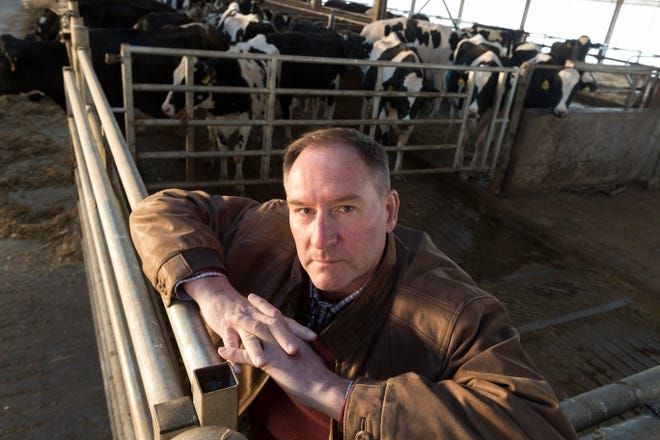

At Roecker’s Rolling Acres, you’d never know anything was amiss. It’s a showcase operation that has hosted many foreign visitors touring Wisconsin dairy farms.

The 300-cow operation has been in Randy Roecker’s family since the 1930s. He’s an experienced farmer and board member of Dairy Management Inc., the national organization that promotes dairy products through ad campaigns such as “Undeniably Dairy.”

Thirteen years ago the farm underwent a major expansion costing about $3 million.

It was aimed at keeping the farm up to date, and to bring Randy’s two children, now adults, into the operation as his parents, now in their 80s, ease out.

“It’s not all gloom and doom in the dairy industry,” Roecker said. “But in order to survive, in any business, you have to grow. If you don’t, you’re falling behind.”

Still, the debt, and the recession that followed the expansion, triggered financial stress that became unbearable. The farm was losing up to $30,000 a month, undermining years of hard work and careful planning for the future.

That’s when Roecker’s depression kicked in.

“I just felt so alone. There was nobody to help me get through all this stuff,” he said. “It got to the point where I wanted to die every day.”

He couldn’t turn it off at night, either.

“All of this starts playing with your mind,” Roecker said. “You try to sleep, and it gets worse because it’s all going through your head. You feel like everything’s spiraling out of control.”

And, that’s exactly what happened.

One time he found himself in the barn, looking up at some ropes in the hayloft. More than once he had contemplated ending his life by suicide, and it scared him.

“I never had problems with depression before, but when this hit me, it was bad,” he said.

Farmers push back against depression

Roecker was hospitalized three times for depression. Over a period of about seven years he battled it with therapy and antidepressant medications which, as a side-effect, can increase suicidal thoughts.

Some people knew he was struggling but didn’t step up to help. His wife of 32 years, overwhelmed with the stress from the farm, filed for divorce.

“I felt like all of my friends just dropped me, that no one wanted anything to do with me,” Roecker said. “I felt like I was suffering alone in silence. The awareness of depression is out there, but we still have to shed this stigma of not talking about it.”

With help from a therapist, he gradually started getting his life back in order. Then the 54-year-old farmer heard about Statz’s death.

“It just put me back where I was,” Roecker said. “I told my therapist, that since I have gone through this myself, and there is just nobody out there helping farmers deal with this, I feel like it’s my calling to do something.”

Roecker, Brenda Statz and fellow church member Dale Meyer, a retired police detective, organized “Farm Neighbors Care” events at St. Peter’s church.

At one of those meetings in early December, farmers talked openly about their struggles with stress, depression and financial hardships.

About 40 people, including some who were not St. Peter’s parishioners, met in the church basement for a lunch of turkey sandwiches, soup and cookies served in exchange for a free-will offering.

They chatted about the wet fall harvest and how challenging it had been for farmers to get crops out of the fields. There was a lighthearted, humorous presentation from Ben Bromley, a former Baraboo News Republic columnist.

Then the discussion turned serious, with presentations from farmers, parishioners and public health officials who offered resources for anyone experiencing mental health issues.

“Leon was a member of this church. He was stressed out, but we felt that we didn’t do what we should have for him,” Meyer said. “And in Randy’s situation, people knew about it, but nobody got around him and said ‘Randy, how can we help?'”

One of the takeaway messages was that farmers could also help each other because they understood the unique challenges in agriculture, where the weather and global markets, out of a farmer’s control, can turn their world upside down.

“We’ve had low milk prices for five years … you burn through the equity in your farm because you’re borrowing money to keep going,” Roecker said. “I tell my friends in town, ‘You don’t know what it’s like. We have no savings, no benefits.'”

The handful of meetings this year have drawn farmers from hours away and have been replicated at other churches in Wisconsin, Minnesota and North Dakota.

“I want other farmers to be able to reach out to me,” Roecker said. “I have gotten calls from people in four or five states. The biggest thing is to just listen.”

Help is available for farmers

For some, the notion of friends, neighbors and relatives knowing about their mental health issues is simply too much, even if they would understand. But there are confidential services anyone can turn to for help, and that includes places that understand farmers.

The Wisconsin Farm Center, part of the state agriculture department, has a staff very familiar with farming. The Madison-based agency offers a wide range of free services including help sorting out farm finances. They offer vouchers that farmers and their families can use to get counseling at clinics across the state.

“We want farmers to feel like they’re being understood. You’d be surprised at how much just spending an hour with someone can help,” said Angie Sullivan, the Farm Center’s agriculture program manager.

The agency has a mediation service that can give farmers some relief from creditors. Also, there’s help available for settling family disputes, like when different generations disagree on their farm’s path forward.

“Let’s talk about some ways you can manage this really difficult time in your life,” Sullivan said. “We can sit at your kitchen table as many times as you need us, to go over your financial picture or your transition plan.”

Some of the agency’s staff are ex-farmers or are still farming. Some have 30 years’ experience in agricultural banking and other areas of agribusiness.

“What we’re seeing, unfortunately, is many farmers have not been able to pay back their operating loans for the last couple of years. Many are stressed to the limit credit-wise,” Sullivan said.

The group Farm Aid offers similar assistance. Its (800) FARM-AID crisis line provides services to farm families, and its Farmer Resource Network connects farmers to organizations across the country.

“In the last two years we have seen a pretty drastic increase in the number of calls, as well as the number of calls that have a crisis component,” said Madeline Lutkewitte, manager of the Farm Aid crisis line based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“We have had a lot of calls from people in dairy farming who just haven’t been able to keep up with their bills and can’t get loans for the remainder of the year and next spring,” she said.

This winter, Wisconsin farm couples can attend workshops in Mineral Point, Wausau, Appleton, Waupun, Eau Claire and Rice Lake, aimed at helping them manage stress associated with financial problems.

The workshops, sponsored by the state agriculture department and University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension, will include a segment on how to talk with children about problems on the farm, and decision-making when the farm may have to shut down.

“Our mission is to keep people farming … but sometimes there are no options except to leave, so we want to do whatever we can to help people be prepared for that, and to make it through that time as a couple and a family,” Sullivan said.

Dairy farmers are especially vulnerable

Leon Statz’s identity was in being a dairy farmer, and it showed in everything he did.

Year after year, he won awards from his cooperative, Foremost Farms, for producing high-quality milk. His wife, Brenda, displayed those awards at his funeral, thinking Leon would have liked that.

“His pride was in producing a quality product,” she said.

And he lived for the challenge.

So when Leon’s depression became so bad that he hadn’t worked in months, he sank in despair.

“His philosophy was, if you weren’t working, you weren’t worth anything,” Brenda said.

He would try to help out a neighbor on their farm but would be overcome with anxiety that he might do something wrong, that some machinery might break while he was operating it.

“He would leave me notes and say, ‘I am trying to do the best I can,’” Brenda said.

Since Leon’s death, she has become an advocate for farmer mental health and suicide prevention.

There aren’t many reliable statistics on farmer suicide rates, but experts say that dairy farmers are especially vulnerable because their lives are inseparable from their work – cows must be milked two or three times a day, 365 days a year.

“We only went on one vacation, ever, with our kids when they were little,” Brenda said.

Often, farmers experiencing depression will isolate themselves. They don’t visit with neighbors as much as they used to, or they may spend more time in the barn alone. Some will make their death look like an accident.

Farmers are private people, and if they reach out for help, you had better take it seriously, Brenda said.

At the Farm Neighbors Care meeting at St. Peter’s church in Loganville, ex-dairy farmer Steven Rynkowski opened up about his story and delivered a heartfelt rendition of the song “Take Heart My Friend.”

For much of his adult life he had experienced episodes of depression. Then, his farm ran into trouble following an expansion that pushed him into financial difficulties.

He overdosed on alcohol and pills, maybe not a suicide attempt, but it sent him to the hospital.

Three years after his overdose, and 30 years after he started dairy farming right out of high school, Rynkowski quit the business.

“It was very hard on me because farming was my way of life,” he said.

He’s since helped other farmers face the end of their career.

“I don’t wish what I went through on anybody. But because I went through it, I am a different person, a better person. … It’s not going to be an easy road out of it, but there is life after dairy farming,” Rynkowski said.

He added: “My faith has a lot to do with it. You are a child of God, and you have worth well beyond farming or whatever it is you do for a living.”

If you or anyone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline, at (800) 273-8255, for immediate help.