Banks should not advance large loans to farmers, least of all to those in the poultry business, an exasperated Ramesh Mehla said over the phone. He should know, for the Mehla family has been fighting to save their agricultural land in Karnal, Haryana, from being auctioned by banks.

October was a harrowing month: dealing with recovery agents, settling a part of the loan by pawning gold jewellery, and rescuing Mehla’s cousin, 28-year-old Sandeep, who attempted suicide by taking poison and survived after spending three nights in an ICU.

It all started in February this year, when social media rumours linking consumption of chicken and eggs to the novel coronavirus spread like a wildfire. As consumption collapsed, farmers were forced to bury live chicks, starve their chicken to death and destroy their daily harvest of eggs.

In a sense, the poultry industry in India, valued at around ₹1.3 trillion was an early victim of the covid-19 pandemic, much before the stringent lockdown in end March impacted other sectors.

“We had a (outstanding) loan of ₹1.5 crore and the land was mortgaged to banks,” Mehla said. “We pleaded with the banks to give us time till December but they won’t listen. Now one of my uncles has shut his layer farm (which produces eggs). It will take months to make good the losses.”

About 70% of the poultry businesses in our area are out of business, said Yudhvir Singh Ahlawat, a farmer leader from Bhiwani in Haryana. Saddled with large losses they have no working capital left to restart their business. Suppliers are unwilling to extend feed or chicks on credit, leading to a demand-supply mismatch in the end market, Ahlawat added.

The hammering of the poultry business explains a peculiar aspect in India’s retail inflation basket—despite falling incomes and a corresponding dip in demand, protein inflation has remained stubbornly high in recent months.

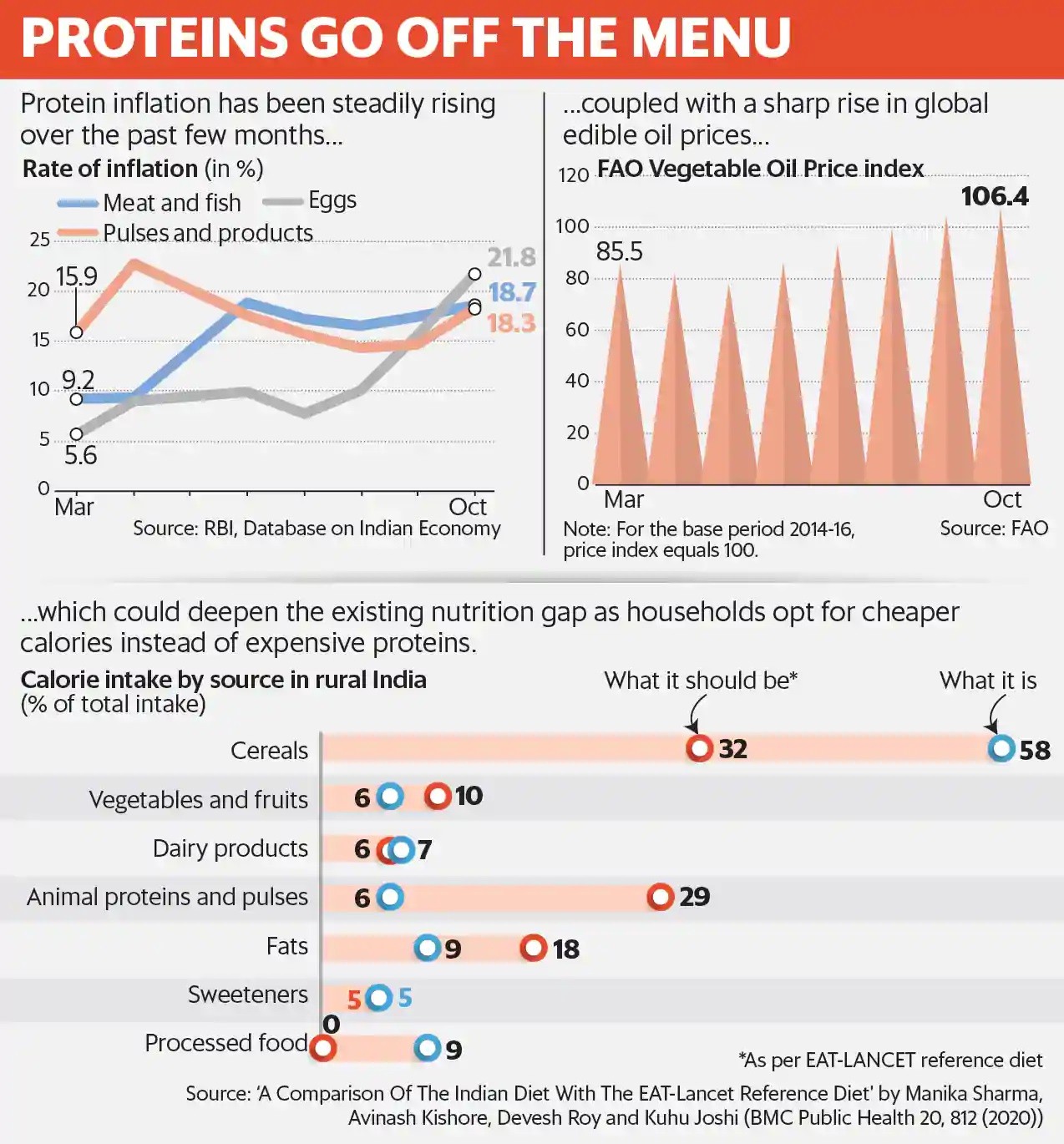

In October, retail prices of meat, fish and egg grew at 19-22% year-on-year. At 18% higher prices, pulses too were significantly expensive compared to last year. The only solace is that consumers were spared a spike in retail prices of milk and milk products, primarily because the pandemic did not impact the dairy supply chain (though farmers incurred heavy losses due to lower procurement and a fall in consumption as hotels, restaurants and catering came to a grinding halt).

Coupled with higher year-on-year prices of vegetables like onions and potatoes following production losses due to excess rains, retail food inflation spiked to 11% in October, the highest since January.

“The high protein inflation is a transitory phenomenon reflecting the demand-supply gaps,” said Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist at Crisil Ltd. “The overall high inflation shows that food demand has been robust unlike discretionary purchases. But we can expect this to cool down in the next few months as farmers respond to the rise in prices by augmenting production,” added Joshi.

Nutrition gap

Currently poultry meat is retailing at over ₹200 per kg while eggs are selling between ₹7-10 per piece, a steep rise from last year. And poultry prices may take months to moderate—largely because of the time it takes to get the production cycle back on track.

High prices of eggs, in particular, also threaten to worsen the nutritional standards of poorer households. Cereals constitute about 47% of the average Indian diet and 70% of the calorie consumed by the poorest rural households—indicating an excess consumption of cheap carbohydrates and not enough of proteins, fruits and vegetables, found a June 2020 study by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

The share of calories from protein sources was only 6-8%, compared to 29% in the ideal (reference) diet.

A peculiar aspect of the Indian diet is that cheaper cereals like rice and wheat contribute about 70% of the protein consumed by households, said Avinash Kishore, research fellow at IFPRI’s Delhi centre.

“In an ideal situation, we should be consuming more eggs, fish and pulses. And India is already paying a price for keeping rice and sugar cheap (plus junk food) which has led to a dual problem: the coexistence of hidden hunger due to protein and micronutrient deficiency alongside obesity. Often, the same person can be anemic and obese. The solution lies in stabilizing prices of proteins such as pulses by increasing availability.”

Disruption in poultry

Currently poultry production is about 75% of the normal and by February (next year), we can expect a 90% sales recovery. So, despite consumer budgets diverted to essential food items, retail chicken and egg prices are still moderate,” said Prasanna Pedgaonkar, a Mumbai based general manager working with Venky’s, among the largest poultry processors in India.

Ashok Kumar, former president of the Karnataka poultry farmers and breeders association, explains why it could take up to a year (counting from February onwards) for the production cycle to normalize. “It takes about 40 weeks to prepare a bird till it starts laying eggs—and production can’t be suddenly ramped up responding to a recovery in demand.”

A 10,000 bird broiler unit (for meat) needs an investment of about ₹10 lakh and it takes about 45 days to ready the birds for consumption. For a 30,000-bird layer firm, one needs to invest about ₹1.5 crore. “It is a risky venture. The pandemic wiped out these investments (back in 2016 the industry received a blow due to demonetization) and many farmers were forced to sell their land,” said Ahlawat, the farmer leader from Haryana.

A single estimate is reflective of the extent of the damage. The losses suffered by the poultry industry in February and March actually wiped out the entire year’s (2019-20) profit, said Ashish Modani, vice-president at ICRA Ltd. “For those who are in the business, realizations are at the pre-pandemic level. We can expect production to normalize soon (in a few months) but prices may not come down drastically from the current levels due to rising feed prices,” Modani added.

Pulse of the matter

The first advance estimates of Kharif crop production released by the agriculture ministry in September showed that production of rain-fed pulses to be significantly higher, from 7.7 million tonnes last year to 9.3 million tonnes in 2020-21 due to higher plantings.

The 21% higher production numbers, however, could be underestimating damages to moong, arhar and urad crop varieties due to excess rains in late August and September in states like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. This partly explains the increase in pulse prices (18% higher year-on-year in October) in the retail inflation basket.

For instance, Abhishek Raghuvanshi, a farmer from Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, harvested a meagre 25 quintals from 90 acres of urad plantings. “In a normal year, the yield would be about 180 quintal. Lower than estimated production is a reason why urad is selling at a premium of up to ₹8,000 per quintal despite subdued demand (compared to support prices of ₹6,000 per quintal),” Raghuvanshi said.

Sizeable procurement of Kharif pulses by the government has also played a role in lifting prices, said an industry insider who did not want to be named. The centre has so far approved procurement of 4.5 million tonnes of pulses and oilseeds at minimum support prices. As government agencies liquidate these stocks in the market, wholesale prices will cool but retail transmission could take longer.

Global tailwinds

Consumers in India can expect retail food prices to moderate by February-March, when supply of proteins as well as widely consumed perishables like onions and potatoes are likely to normalize. Prices of green vegetables are expected to soften with the arrival of winter.

However, high global food prices remain a key concern. Global food prices rose for the fifth consecutive month in October led by cereals, sugar, dairy and vegetable oils, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said in its monthly Food Price Index report.

While higher cereal prices benefited farmers in India by expanding exports of rice, the rise in edible oil prices had firmed up retail food inflation since India imports about 70% of its domestic requirement. Led by firm palm and soybean oil prices, the FAO vegetable price index rose by 1.8% during October to a nine-month high. Domestic prices are also higher as the Centre raised import duties to boost local production.

The current steep prices of items comprising the retail food basket—be it eggs, pulses or vegetables—is evidently taking a toll on millions of households. And the pandemic could be worsening India’s nutritional standards.

Even before the pandemic hit, a leaked government survey showed a sharp 9% fall in rural consumption, including on staples, between 2011-12 and 2017-18. A more recent survey by ActionAid India found that about a fifth of the surveyed families did not have enough food for two meals a day.