The adulteration of milk with chemicals and water is ubiquitous among unscrupulous suppliers, a practice that poses a risk to consumers. But the way milk evaporates may help discern its purity.

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, have developed a “low-cost and effective method” to detect the presence of urea and water in milk, by analysing deposition patterns after evaporation. Their findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal, ACS Omega.

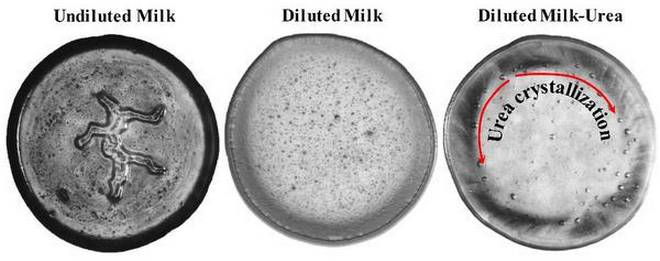

To determine the presence of adulterants, the researchers studied evaporative deposition patterns, which emerge when a liquid mixture like milk completely evaporates, causing volatile components to dissipate, and solids or non-volatile components to arrange themselves in distinctive patterns.

“Milk with and without water or urea showed very different evaporative patterns. In unadulterated milk, the evaporative pattern consisted of a central, irregular blob-like pattern. Water was found to cause distortion or complete loss of this distinctive pattern, depending on how much is added,” stated IISc in a press release.

Urea completely erases the central pattern. “As it is a non-volatile component, it does not evaporate but instead crystallises, starting at the interior of the milk drop and extending along the periphery,” it added.

With this method, the IISc team was able to detect water concentrations as high as 30% and urea concentrations in diluted milk as low as 0.4% using this type of pattern analysis. According to the researchers, the technique can be a replacement in the absence of equipment.

“It can be done in any place. It does not require a laboratory or other specialised processes, and can be easily adapted for use even in remote areas and rural places,” said Virkeshwar Kumar, a postdoctoral researcher. He developed the technique along with Susmita Dash, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, IISc.

The researchers believe that this technique can potentially be extended to test for adulterants in other beverages and products too. “The pattern that you get is highly sensitive to what is added to it,” said Susmita Dash in the release. “So, I think this method can be used to detect impurities in volatile liquids. It will be interesting to take this method forward for products such as honey, which is often adulterated.”

Expanding the scope

Once the patterns for all adulterants and their combinations are standardised, they can be fed into an image analysis software, for example, which would compare a photo of the sample’s evaporative pattern with other standard patterns to accurately detect the adulterants present.

“The next step that we are looking at is to test for a lot of other adulterants, such as oil and detergents that form an emulsion resembling milk,” said Susmita Dash.