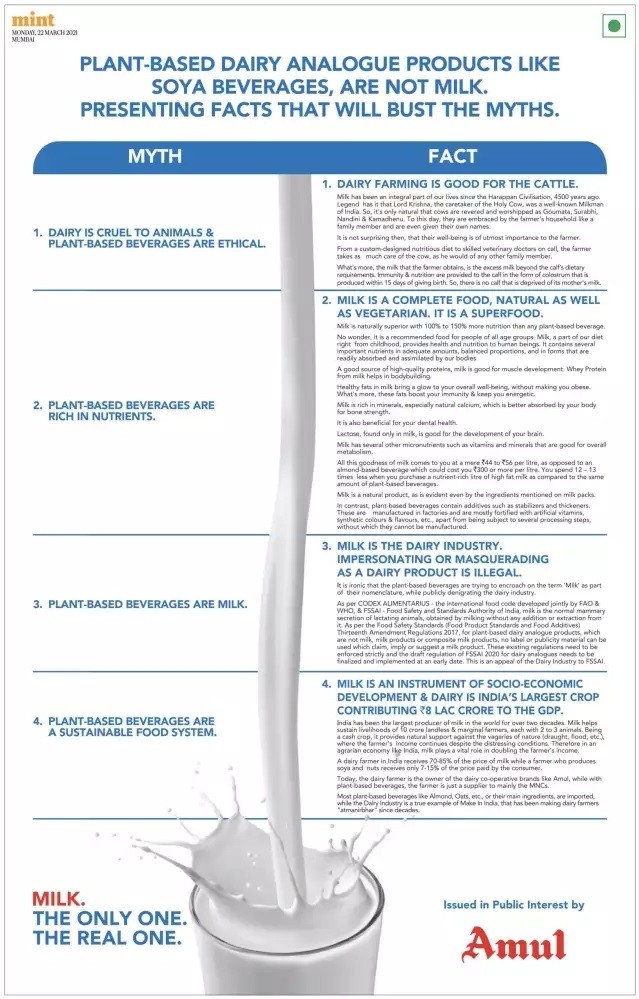

The Amul ad released last week on plant-based analogue products (like soya milk) versus real ‘milk’ should have sparked more discussion and debate than it has. Amul has raised a very basic question: what is ‘milk’ and is anything but dairy milk qualified to be called milk? So is soya milk or oat milk or almond milk or coconut milk really milk? Or are they conveniently spawning off the goodness of milk?

Amul’s contention is really simple. Milk is the dairy industry. Impersonating or masquerading as a dairy product is illegal. Amul believes that it is ironic that plant based beverages are trying to ‘encroach’ on the word ‘MILK’. As per the CODEX ALIMENTARIUS – the international food code developed jointly by FAO, WHO and FSSAI, milk is the normal mammary secretion of lactating animals, obtained by milking without any addition or extraction from it. The Amul ad goes on to quote the Food Safety Standards (Food Product Standards and Food Additives) Thirteenth Amendment Regulations 2017 that says that for plant based dairy analogue products, which are not milk, milk products or composite milk products, no label or publicity material can be used which claims, implies or suggests a milk product.

Why is Amul getting so aggressive about ‘milk’? Well, the battle to protect its ‘milk’ turf is not really new. Amul simply believes that only milk is milk, and anything that is not really milk is not milk! It is as simple as that. So over the years, Amul has been at the forefront of many battles where the equity of milk has been challenged in any which way.

The most recent of these ‘milk’ centric battles has been of ice-cream versus frozen desserts. In March 2017, Amul launched an ad campaign for its Amul brand of ice-creams that emphasized the difference between ice-creams (made from milk fat) and frozen desserts (made from vegetable oil). These definitions, it said were based on ingredients as per Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) norms. Amul’s ads urged customers to choose ice-creams over frozen desserts, claiming that the latter were made with vanaspati ‘tel’ or vegetable oil. HUL filed a lawsuit in the Bombay high court asking that Amul be stopped from airing the ads. HUL argued that as Kwality Wall’s was the largest frozen dessert brand in India, it was directly hit by Amul’s advertisement even though the films did not refer to it by name. A single-judge bench of Justice S.J. Kathawalla granted HUL’s plea for an injunction against the Amul advertisements.

But Amul by then had succeeded in its basic intent behind the communication: to sow seeds of doubt vis-à-vis ‘ice-cream’ not made from milk. The dairy industry (led by Amul) has led a campaign for years that only ice-cream containing 10 per cent milk fat can be called “ice-cream”. If the milk fat is replaced by vegetable oil, the resultant product can only be called “frozen dessert” even if it contains 11 per cent SNF (solid non fat) from milk (because the “cream” in ice-cream can only be derived from milk).

Controversy on what is real and what is not real vis-à-vis milk is not new. It goes back actually to the 1930s. Lever Brothers imported vanaspati ghee into India in the 1930s as a cheap substitute for desi ghee or clarified butter, prepared from cow’s milk. Ghee was an expensive product even back then and something that was used sparingly in Indian households – over weekends or when preparing a delicacy or a dessert. Vanaspati ghee, on the other hand, was a type of vegetable shortening made up of hydrogenated or highly saturated vegetable oil and made to mimic desi ghee. The original brand was called Dada but Lever inserted an ‘L’ in the middle of the Dutch brand name and rechristened it Dalda. Dalda’s advertising, created by their ad agency Lintas, in the initial years drove home the point that Dalda tasted just like desi ghee, had deep-frying properties like it, but unlike ghee, it didn’t feel heavy either on the pocket or on the palate. In the 1950s, there was a concerted call for a ban on Dalda, because it was a “falsehood” – a product that imitated desi ghee, but was not the real thing. In other words, critics argued that Dalda was an adulterated form of desi ghee, harmful for health.

And millions were being deceived by its continued usage. The Prime Minister of the day, Jawaharlal Nehru, called for a nationwide opinion poll, which proved inconclusive. A committee was set up by the government to suggest ways to prevent adulteration of ghee. But nothing came of it eventually. The monopoly of Dalda continued to the 1980s, without much challenge. Amul was of course not around at that time and had nothing to do with the desi versus vanaspati fight back then.

Amul’s offensive against anything that is not ‘real’ milk based however has extended to other categories too … when Kissan recently launched peanut ‘butter’, Amul retailed its own product with a very specific launch of Amul peanut ‘spread’. The nuance of butter versus spread was not lost on anyone.

The longest drawn out controversy has of course been that between butter and margarine. Butter and margarine look similar and are used for the same purpose in the kitchen. While butter is high in saturated fat, margarine is rich in unsaturated fat and sometimes trans fat. But it is the ‘pass-off’ of margarine as butter-lite or even ‘better butter’ that has led to much bad blood over the years. In 2010, Amul in fact spoofed Zydus’s Nutralite advertising. The setting in both ads was similar – the lady of the house was seen spreading a meal and the husband was seen enjoying a paratha topped with a generous helping of butter. The Nutralite ad showed the lady spreading ‘healthy alternatives to butter’, while Amul’s commercial showed the lady serving ‘nonsynthetic, real and safe butter, free of chemicals.’ Amul had basically taken head-on Nutralite’s claim that it was ‘better than better’. Amul felt that Nutralite’s advertising was ‘denigrating and discrediting’ to butter as a category. Hence the counter offensive.

There is still more to the story. Amul took its milk and butter turf war to cookies too. Amul in 2019 released an ad that claimed that other biscuit manufacturers used just 0.3-3% butter and 20-22% vegetable oil in their cookies. Amul butter cookies, on the other hand it said had 25% butter and no vegetable oil. The ad did not name Britannia, but the biscuit in question was clearly their product. In response, Britannia released an ad without naming anyone too, but posed a question, “How much cholesterol does a 25% butter cookie have?. Approximately 7 times of cholesterol.”

Amul’s latest offensive to get almond milk or oat milk to be re-nomenclaturised as almond ‘beverage’, or similar, is perhaps triggered by the belief that the top-end (read affluent and health conscious) customers are deserting the ‘pure milk’ franchise that it sees itself as a custodian of. ‘Lactose-averse’ is the commonest ailment amongst the affluent sections of society. So substitutes from almond or soya or others are finding a place on breakfast tables. That too when the purest of full fat milk costs Rs. 60-70 while soya milk may cost Rs. 100, oat milk about Rs. 200 and almond milk maybe Rs. 300 or more. Amul thinks these other ‘milks’ are not really milk and the claims to be milk of any sort are legally not tenable. That farmers on an average have 2-3 milch cattle, that the livelihood dairy farming supports is very important, that the Indian economy needs the milk and its producers, and similar other arguments are just emotional and rational supports to the bigger story that plant based substitutes are not milk by any other name.

But this logic may not apply to coconut milk which has carried the ‘milk’ epithet for thousands of years and is a traditional consumption and cuisine item not just in South India but in most South East Asian countries as well as South America.

In any case, why is Amul putting out ads such as this? My personal view is that protecting its milk turf is a political and economic compulsion for GCMMF … it is the Big Bully of the milk business and periodically needs to flex its muscles. For now plant based substitutes hardly dent Amul’s sales in any significant way. They are not even likely to do so in the near future. But they still provide an excuse to rave and rant against anything and everything that is deemed to be masquerading as ‘the real thing’. It is also a good way of signaling supremacy in its realm for Amul and also extolling the virtues of its mainstay – milk, while underlining to consumers that Amul equals milk more than ever!

The only real solution maybe in Amul trying to obtain a GI-tagging for Indian Milk, Indian Butter, Indian Ghee and Indian Ice-Cream. That too may not be possible because GCMMF may be India’s largest producer of milk and milk products but than every Verka, Vita and Saras may want Punjab Milk, Haryana Milk and Rajasthan Milk to be separately protected. And in any case, every farmer with his two cows has equal rights to the now generic words … milk, butter, ghee or ice-cream.

The author is a media and advertising veteran. Views expressed are personal.